A Titan Among Beasts: What Was the Aurochs?

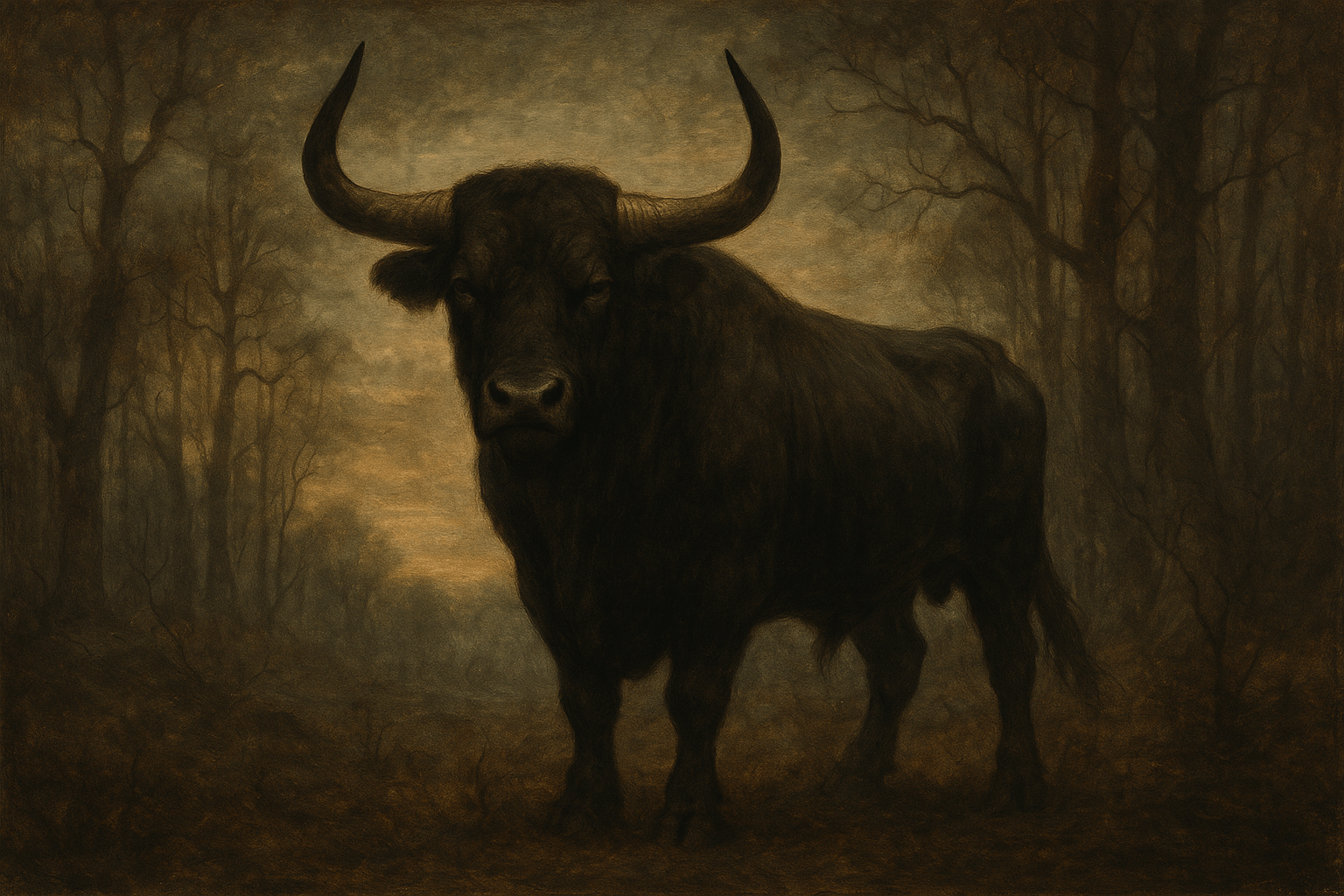

Before we can understand its loss, we must first appreciate what the aurochs was. Forget the placid dairy cows in rolling fields. The aurochs was a creature of primeval power. Standing up to 1.8 meters (nearly 6 feet) at the shoulder, a large bull could weigh over 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds). They possessed massive, forward-curving horns, a shaggy coat—typically black in bulls and reddish-brown in cows—and a temperament that was anything but docile. Roman accounts, including those of Julius Caesar, described them as creatures of immense strength and ferocity, second only to the elephant in size and untamable by man.

For millennia, the aurochs was intertwined with human history. It thundered across the grasslands and forests of Eurasia, from the British Isles to the Korean peninsula. Our Paleolithic ancestors immortalized it in the stunning cave paintings of Lascaux and Altamira, capturing its raw vitality with awe and respect. For early humans, the aurochs was a source of meat, hide, and bone, but also a potent symbol of nature’s untamed spirit. It was the wild heart from which our domesticated world sprang.

A Kingdom Shrinks: The Long Decline

The aurochs’ decline was a slow, inexorable process spanning thousands of years. As human civilization expanded, the wild world shrank. The primary drivers of its demise were:

- Habitat Loss: Forests were cleared for agriculture, and wetlands were drained. The vast, unbroken wilderness the aurochs needed to thrive was carved into smaller and smaller pieces.

- Competition with Livestock: The aurochs’ own domesticated descendants became its rivals, grazing on the same pastures and pushing their wild ancestor into ever-more-marginal lands.

- Disease: Proximity to domestic cattle, which numbered in the millions, exposed the dwindling aurochs population to diseases for which they had no immunity.

- Overhunting: As a symbol of power and a formidable trophy, the aurochs was a prized target for hunters, particularly nobility.

By the late Middle Ages, the aurochs had vanished from most of Europe. Its once-vast kingdom had been reduced to a few isolated pockets in the remote forests of Prussia, Lithuania, and, most importantly, Poland.

The Royal Preserve: History’s First Conservation Effort?

It was in the Kingdom of Poland that the final, most fascinating chapter of the aurochs’ story unfolded. By the 15th century, Polish kings and Lithuanian Grand Dukes recognized the animal’s rarity and immense prestige. The remaining aurochs were no longer just game; they were a living crown jewel.

What followed can be seen as a prototype for modern conservation, albeit driven by elitism rather than ecological concern. The last significant herd, located in the Jaktorów Forest about 55 kilometers southwest of Warsaw, was placed under royal protection. This was no mere suggestion; it was the law of the land.

Hunting the aurochs became a crime punishable by death. The forest and its magnificent inhabitants were the exclusive property of the king.

To enforce this, a unique system was established. Several local villages were tasked with the care of the aurochs. These villagers, known as “gamekeepers”, were responsible for guarding the animals from poachers, monitoring their numbers, and even providing them with hay during harsh winters. In exchange for this vital service, they were granted a unique privilege: exemption from serfdom and local taxes. They were free men, serving the king by serving the aurochs. For a time, this royal decree and local stewardship seemed to work, creating a protected sanctuary for the last of the titans.

The Final Countdown: Why Did the Effort Fail?

Despite this well-intentioned, centrally managed effort, the aurochs’ fate was already sealed. The Jaktorów herd was a textbook example of an extinction vortex—a small, isolated population spiraling towards oblivion.

A royal census from 1564 provides a chillingly precise snapshot of the decline. The survey recorded just 38 individuals: 22 cows, 3 old bulls, 8 young ones, and 5 calves. This tiny gene pool made the population dangerously inbred and highly susceptible to any external shock. The protection, while noble, addressed only one threat (hunting) while others festered:

- Disease: The most likely immediate cause of the final collapse was a disease outbreak, probably passed from domestic cattle grazing near the forest’s edge. A small, genetically weak population would have been devastated by an epidemic.

- Poaching: While officially forbidden, it’s likely that some illegal hunting continued, especially as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth faced increasing political turmoil and war in the early 17th century.

- Deteriorating Protection: As the kingdom’s resources were diverted to military conflicts, the enforcement of the aurochs’ protection likely weakened. The special status of the gamekeepers may have been ignored by local nobles, and the system began to break down.

The numbers continued to drop. By 1601, only four aurochs remained. By 1620, just one. For seven years, a single female aurochs wandered the Jaktorów Forest, a living ghost of a bygone era. Her death in 1627 was the quiet, lonely end of a lineage that had stretched back hundreds of thousands of years.

Legacy of the Lost Giant

The story of the last aurochs is a profound historical lesson. It demonstrates that good intentions are not enough. The Polish kings’ effort failed because it lacked a scientific understanding of population genetics, disease ecology, and habitat viability. They built a fence around the problem but couldn’t stop the invisible threats of sickness and genetic decay from seeping through.

Today, scientists have attempted to “breed back” the aurochs through projects like the creation of Heck cattle, using primitive domestic breeds to select for aurochs-like traits. While these animals may resemble the lost giant, they are only a faint echo. The true genetic blueprint and wild spirit of Bos primigenius are gone forever.

The aurochs lives on in the DNA of the more than 1.5 billion cattle that now populate our planet. Every time we see a herd of cows, we are seeing the domesticated legacy of that magnificent wild beast. But the story of its final days in a Polish forest serves as a powerful and timeless warning: extinction is forever, and even a king’s command cannot turn back the tide once it has begun to recede.