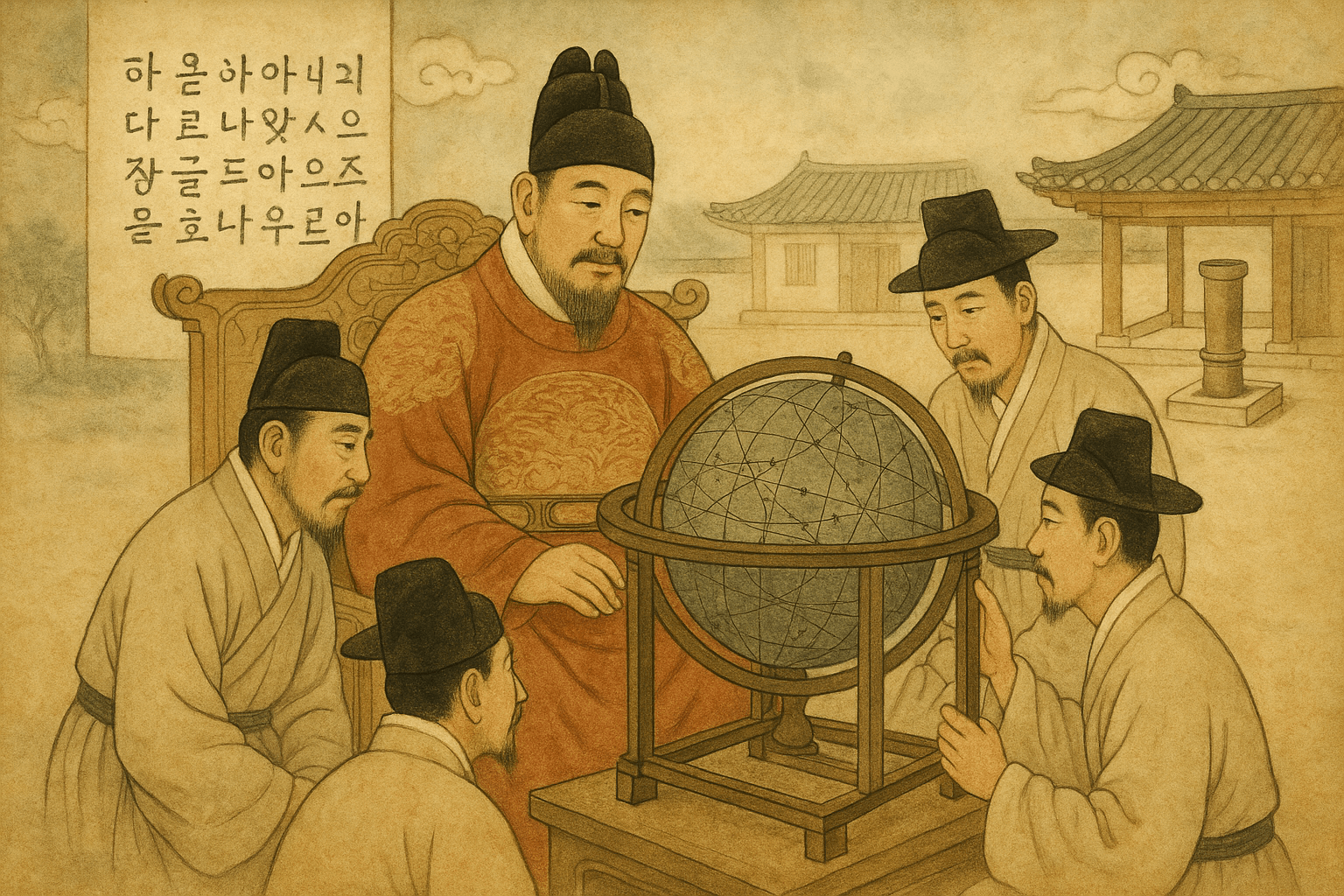

At the heart of this incredible period was one of history’s most remarkable monarchs: King Sejong the Great (r. 1418–1450). Far more than a mere ruler, Sejong was a scholar, a linguist, a strategist, and a patron of genius. He understood that a nation’s strength lay not just in its armies, but in the well-being and knowledge of its people. To achieve this, he established the Jiphyeonjeon, or “Hall of Worthies”—a royal think tank where the brightest minds in the kingdom gathered to solve the nation’s most pressing problems.

A Revolution in Language: The Birth of Hangul

Perhaps the most profound and enduring of Sejong’s projects was the creation of a new alphabet for the Korean language. Before the 15th century, Koreans relied on classical Chinese characters (Hanja) for writing. This system was notoriously difficult to master, requiring years of dedicated study. As a result, literacy was a privilege reserved for the aristocratic elite, creating a vast cultural and administrative chasm between the rulers and the ruled.

King Sejong saw this as an injustice and a practical obstacle to governance. In his own words, the spoken language of his people was “different from that of China” and did not “flow smoothly” with Chinese characters. Many commoners, he noted, were unable to express themselves in writing, even when they had legitimate grievances.

His solution was a stroke of scientific genius: the Hunminjeongeum (“The Proper Sounds for the Instruction of the People”), today known as Hangul. Unveiled in 1446, this new alphabet was not an adaptation of an existing script but a completely new invention based on the science of phonetics.

- Consonants were designed to mimic the shape of the mouth, tongue, and throat when producing a specific sound. For example, the consonant ‘ㄱ’ (g/k) represents the shape of the tongue’s root blocking the throat.

- Vowels were created from three simple strokes representing the core philosophical concepts of Heaven (•), Earth (ㅡ), and Humanity (ㅣ).

The system was so simple and logical that a learned person could grasp it in a morning, and even a “foolish man can learn them in the space of ten days.” Despite fierce opposition from scholars who felt it was unsophisticated compared to Hanja, Hangul’s creation was a monumental leap forward, paving the way for mass literacy and cementing a unique Korean cultural identity.

Charting the Heavens: Astronomy and Timekeeping

For an agrarian society like Joseon Korea, the sky was not just a source of wonder but a practical guide for survival. An accurate calendar was essential for farming—planting and harvesting at the right time could mean the difference between a bountiful harvest and famine. Astronomy was also deeply intertwined with political legitimacy, as the precision of the royal calendar was seen as a reflection of the dynasty’s harmony with the cosmos.

Under Sejong’s patronage, and with the brilliant inventor Jang Yeong-sil at the forefront, Joseon astronomers made extraordinary advances. Jang, who rose from the low-status cheonmin class to become a high-ranking court engineer, developed a series of groundbreaking astronomical instruments.

One of his masterpieces was the Jagyeokru, an incredibly complex automated water clock. This device didn’t just track time; it announced it. Using a series of levers, pulleys, and bronze balls, the clock would automatically trigger figures to strike bells, gongs, and drums at appointed hours, making it one of the most sophisticated timekeeping devices of its time. Another key invention was the Angbuilgu, a hemispherical sundial that was both scientifically precise and publicly accessible. These sundials were installed in busy public places, allowing everyone, not just court officials, to know the time of day and the changing seasons.

Measuring the Rain: The World’s First Standardized Rain Gauge

While European scientists like Benedetto Castelli wouldn’t conceptualize a modern rain gauge until the 17th century, Joseon Korea was already using one two hundred years earlier. In 1441, the court of King Sejong invented the Cheugugi, the world’s first standardized rain gauge.

This was a profoundly practical innovation. Droughts and floods were a constant threat, and the government’s tax revenue was directly tied to the agricultural harvest. To govern effectively and assess taxes fairly, the court needed accurate data on rainfall across the country. The Cheugugi was the answer. It consisted of a standardized bronze or iron cylinder set into a stone pillar. Officials would measure the depth of the collected water with a standardized ruler and report the findings to the central government.

This wasn’t just a single invention; it was the creation of the world’s first national meteorological network. By standardizing the instrument and mandating its use throughout the provinces, King Sejong’s government was engaging in systematic data collection on a scale unheard of for its time. It was a remarkable example of science being used directly for public administration and economic policy.

The Power of the Press

Korea has a long and storied history with printing. The Jikji, a Korean Buddhist text printed in 1377, is recognized by UNESCO as the world’s oldest existing book made with movable metal type—predating the Gutenberg Bible by decades. However, the Joseon Dynasty refined and expanded this technology to new heights.

King Sejong’s court developed a new, more advanced method of casting type called Gabinja in 1434. This new type was more durable and fit together with greater precision, producing print quality that was far superior to previous methods. The combination of this advanced printing technology and the simple Hangul alphabet was a game-changer. It allowed the government to print and distribute vast quantities of books on agriculture, medicine, ethics, and law, spreading knowledge far beyond the walls of the palace.

A Legacy of Practical Genius

The scientific revolution of the Joseon Dynasty stands as a testament to a unique moment in world history where a monarch, an academy of scholars, and brilliant engineers converged. Driven by a Confucian philosophy that prized practical knowledge for the betterment of society, they created innovations that were centuries ahead of their time. From an alphabet for the people to nationwide data collection, the achievements of this era were not just technical marvels—they were tools for building a more just, prosperous, and enlightened nation. It’s a legacy of practical genius that continues to inspire and resonate today.