Imagine an empire stretching 2,500 miles along the spine of the Andes, encompassing deserts, jungles, and towering mountain peaks. How could such a vast and diverse realm, without wheeled vehicles or a written alphabet, sustain its armies, support its cities, and protect its people from the constant threat of famine? The answer lies not in a secret weapon, but in a marvel of engineering and social organization: the qullqa.

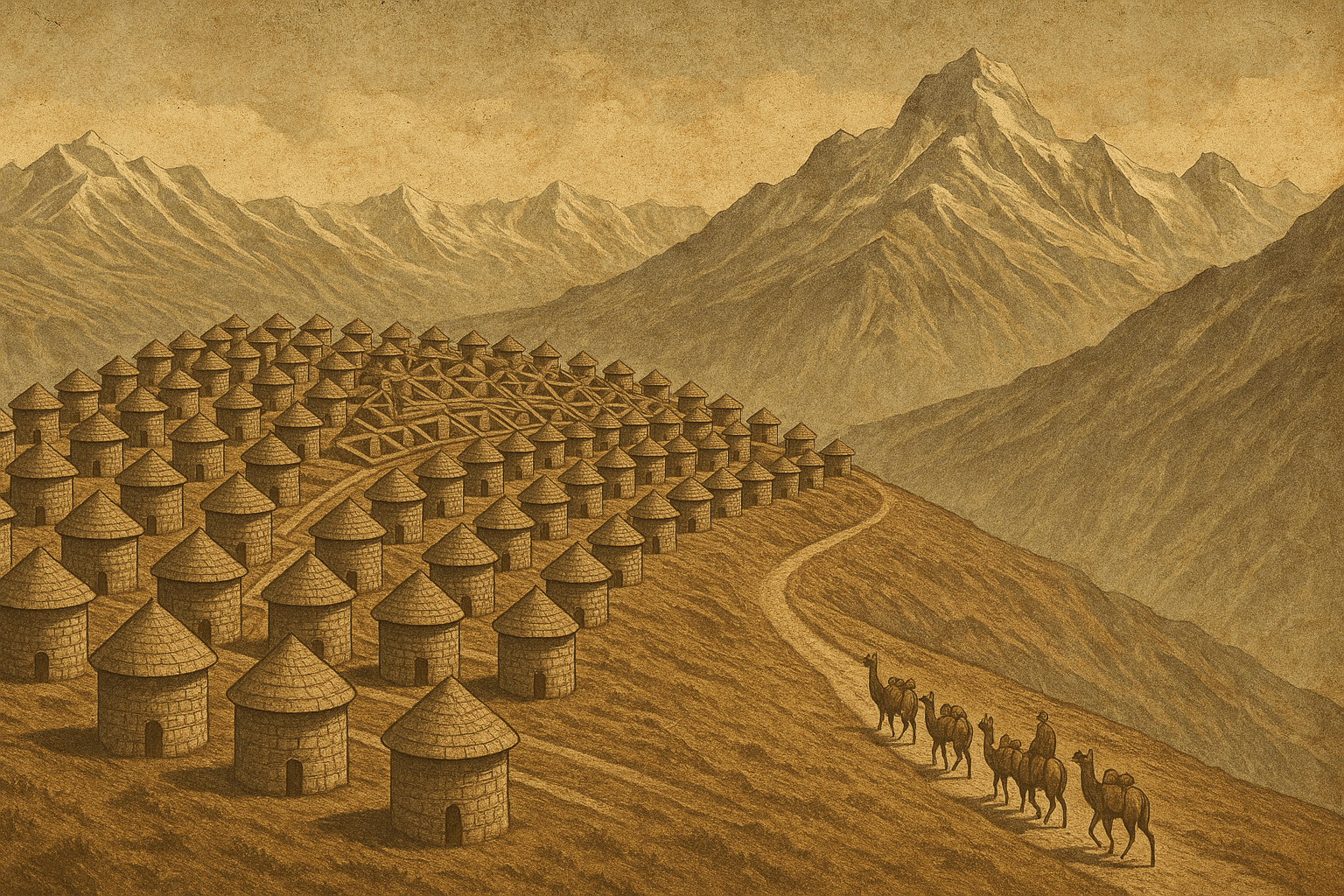

The qullqa (pronounced “kol-ka”) was the Inka storehouse, but calling it a mere granary is like calling a pyramid a pile of rocks. These structures were the lifeblood of the empire, the physical manifestation of its wealth, and the key to its incredible stability. Dotting the hillsides in vast, orderly rows, the qullqa system was a sophisticated network that secured the Inka state against the unpredictable and often brutal Andean climate.

More Than a Pantry: The Pillars of Imperial Power

The Andes are a land of extremes. A year of bountiful harvest could easily be followed by drought, flood, or frost, spelling disaster for isolated communities. The Inka state, however, turned this vulnerability into a source of strength. By implementing a system of agricultural surplus, they created a buffer that could outlast any single-season catastrophe.

This surplus, collected as a labor tax known as the mita, was funneled into the state-controlled qullqas. These storehouses were filled with an astonishing variety of goods, representing the entire output of the Inka economy:

- Staple Foods: Freeze-dried potatoes (chuño), maize (corn), quinoa, and dried meat (charqui or jerky).

- Luxury Goods: Coca leaves, prized for ritual and medicinal use.

- Military Supplies: Weapons, shields, tunics, and sandals for the imperial army.

- Raw Materials: Cotton, wool from llamas and alpacas, and vibrant feathers for fine textiles.

This stored wealth was the engine of the empire. It fed government administrators, priests, and artisans. It supplied the massive armies that marched along the great Inka road, the Qhapaq Ñan. Most importantly, in times of famine, the state would open the qullqas and distribute food to the populace, reinforcing its role as a benevolent provider and ensuring the loyalty of its subjects. A full qullqa was a symbol of security and order.

Architectural Genius: The Air-Conditioning of the Andes

The long-term preservation of food, especially in a region with fluctuating humidity and temperatures, is a monumental challenge. The Inka solved it not with magic, but with a deep understanding of their environment. The design and placement of qullqas were a masterclass in passive, natural engineering.

Strategic Location

Qullqas were almost always built on dry, windy hillsides, high above the valley floors where administrative and residential centers were located. This placement was deliberate. The elevation provided lower temperatures and humidity, while the constant mountain winds wicked away moisture, the primary enemy of stored goods. This strategic positioning was the first line of defense against rot and mold.

Climate-Controlled Design

The Inka further refined their storage technology by tailoring the architectural design of the qullqa to its contents.

Circular qullqas were typically used for storing maize. It is believed their conical roofs and round design promoted a vortex-like airflow, keeping the kernels dry. They were often built on the windiest parts of the slope to maximize this effect.

Rectangular qullqas were generally used for storing tubers like potatoes and their freeze-dried derivative, chuño. These were often built further down the slope. The true genius, however, lay beneath the floor. Inka masons constructed these buildings on foundations with a network of underwater drainage canals and an air-permeable floor made of gravel and paved stone. This allowed cool, dry air to circulate up from underneath, while vents in the walls allowed warm, moist air to escape. This brilliant system created a constant, cool, and dry interior—a natural form of refrigeration.

At major administrative centers like Huánuco Pampa, hundreds of these storehouses stand in silent rows. In the Cochabamba Valley of modern-day Bolivia, the site of Cotapachi once held an incredible 2,400 qullqas, acting as a major grain basket for the entire empire.

A System of Perfect Record

Managing the contents of thousands of storehouses across an empire requires more than just good architecture; it requires impeccable accounting. Since the Inka had no traditional writing system, they used a remarkable device known as the khipu (or quipu).

A khipu was a collection of knotted strings, typically made from cotton or alpaca fiber. A highly trained class of administrators, the khipu kamayuq (“khipu-keeper”), used these devices to record vast amounts of data. Using a decimal system, different types of knots, colors, and cord placements could signify everything from census data to historical narratives. For the qullqa system, the khipu was the inventory ledger. A khipu kamayuq could track exactly how much maize, how many potatoes, or how many woolen tunics were in each storehouse, what was added from the latest harvest, and what was dispatched to feed a moving army. It was a sophisticated system of resource management that was as essential as the storehouses themselves.

The Legacy of the Empty Storehouses

When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the 1530s, they were stunned by the sight of the Inka’s overflowing storehouses. They saw not a system of social security, but a treasure trove to be plundered. They ransacked the qullqas, disrupting the delicate cycle of production, storage, and redistribution that had sustained the Andes for generations.

The collapse of the qullqa system was a catastrophic blow to the Inka world. Without the state’s reserves, regional famines returned with a vengeance. The armies could no longer be supplied, and the foundation of imperial power crumbled. The empty, windswept ruins of the qullqas that still stand today are more than just archaeological curiosities. They are silent testaments to a civilization that achieved extraordinary stability by mastering its environment, planning for the future, and engineering a system that was truly the backbone of an empire.