A Scythe Across Europe: The Black Death

To understand the origin of quarantine, we must first travel back to the mid-1300s. The Black Death, or Bubonic Plague, arrived in Europe like a horrifying, unstoppable tide. Carried by fleas on rats stowed away on merchant ships, the disease swept through the continent with terrifying speed and lethality. It’s estimated to have killed between 30% and 60% of Europe’s population.

Physicians and authorities were helpless. Their medical knowledge, based on theories of imbalanced humors or “miasma” (bad air), offered no effective cures. Yet, amidst the chaos, a crucial observation was made: the disease traveled with people. While they didn’t understand germ theory, they understood contagion. Cities began to take crude defensive measures, shutting their gates to strangers and turning away ships from plague-ridden ports. These were reactive, inconsistent, and often too late.

The Venetian Solution: A Fortress Against Disease

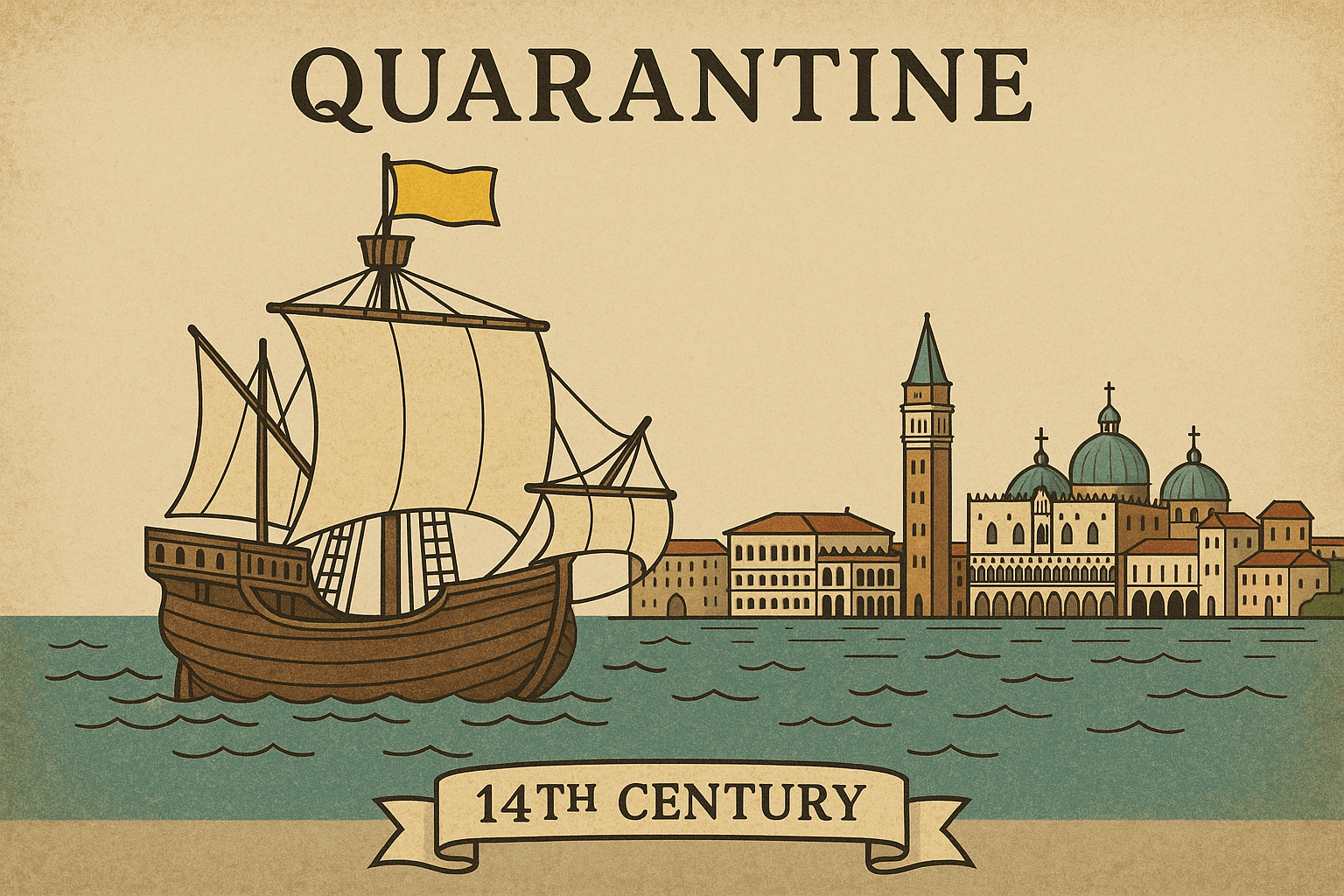

Nowhere was the threat more acute than in the Republic of Venice. As a dominant maritime power and the bustling crossroads of commerce between East and West, Venice’s wealth depended on the very ships that carried the pestilence. To simply close the port was to commit economic suicide. They needed a more nuanced, systematic approach.

The first significant step was taken not in Venice itself, but in the nearby city of Ragusa (modern-day Dubrovnik), then under Venetian influence. In 1377, the city’s council passed a revolutionary law. Any ship or person arriving from a plague-affected area had to spend 30 days in a designated spot outside the city walls before they could enter. This period of isolation was called a trentino, from the Italian for “thirty.” It was the world’s first organized system of medical isolation.

Venice observed this experiment and improved upon it. Recognizing that 30 days might not be enough, they extended the period. The new waiting time was 40 days, or quaranta giorni in Italian. From this phrase, we derive our modern word: quarantine.

Why Forty Days?

The choice of 40 days was likely a mix of pragmatic observation and deep cultural symbolism. While they couldn’t have known the precise incubation period of Yersinia pestis, 40 days was a sufficiently long window to ensure that any infected person would either recover or perish, thus no longer posing a threat. But the number 40 also resonated deeply in the medieval Christian world:

- It recalled the 40 days and nights of rain during the Great Flood.

- It mirrored the 40 days Moses spent on Mount Sinai.

- Most pointedly, it aligned with the 40 days of Lent, a period of purification, penance, and trial.

This blend of empirical evidence and religious significance gave the quaranta giorni a powerful authority that helped ensure compliance.

The Lazzaretto: Institutionalizing Isolation

Holding ships at anchor for 40 days was one thing, but Venice soon realized it needed a more sophisticated infrastructure. In 1423, the Republic established the world’s first maritime quarantine station on the island of Santa Maria di Nazareth, which soon became known as the Lazzaretto Vecchio (Old Lazaretto). The name may have derived from the nearby church or from the biblical figure Lazarus, the patron saint of lepers.

This was not a prison but a complex, state-run public health facility. It was a place where travelers from suspect ships could live out their 40-day isolation in relative comfort. More importantly, it was where confirmed plague victims were sent for treatment and, all too often, to die. Goods were also disinfected—hung in the open air and fumigated with herbs like rosemary and juniper.

The system grew even more advanced with the creation of the Lazzaretto Nuovo (New Lazaretto) in 1468. This second station acted as a filter. Ships were first inspected here, and only suspected cases were sent on to the original Lazzaretto Vecchio. This triage system was a remarkable innovation, protecting the city by separating the potentially sick from the confirmed sick.

From Plague to Polio: The Evolution of an Idea

The Venetian model was a stunning success and was soon copied by other major port cities across the Mediterranean and Europe. For the next several centuries, quarantine became the primary international defense against not just plague, but other terrifying epidemics like cholera, yellow fever, and typhus.

When cholera pandemics swept out of Asia in the 19th century, quarantine stations were established in ports from New York to New Orleans. During outbreaks of yellow fever in American cities, houses marked with a yellow flag were placed under strict quarantine by armed guards.

The practice was not without controversy. Merchants complained of devastating economic losses, and civil libertarians debated the state’s right to restrict individual freedom. Yet, in the absence of cures, it remained the most effective tool available.

The scientific revolution of the late 19th century, led by figures like Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, finally revealed the true nature of contagion: microscopic germs. This new understanding didn’t make quarantine obsolete; it refined it. Instead of isolating entire shiploads of people, authorities could now focus on isolating confirmed patients and monitoring their known contacts. The brute force of the quaranta giorni evolved into the scientifically targeted public health intervention we know today.

An Enduring Legacy

From a small island in a Venetian lagoon to the global lockdowns of the COVID-19 pandemic, the history of quarantine is the story of humanity’s long and ongoing battle against infectious disease. It’s a testament to our ability to learn from observation, to build systems in the face of chaos, and to accept collective sacrifice for the greater good. The word itself is a living monument—a 600-year-old reminder that some of our most modern problems have very deep historical roots.