A Society on the Brink: Ireland Before the Blight

To understand the famine, one must first understand the precarious state of pre-famine Ireland. The country was, in effect, a colonial agricultural outpost of the British Empire. Land ownership was the critical issue. Most of the fertile land was owned by a small class of Anglo-Irish Protestant aristocrats, many of whom were absentee landlords living in England. They rented out their vast estates to tenant farmers, who in turn subdivided the land into smaller and smaller plots for a desperate, growing population.

For the rural poor, who made up the majority of the population, the potato was a miracle crop. It was nutritious and could produce a massive yield from a tiny parcel of land, allowing a family to subsist. This dependence, however, was a ticking time bomb. With no ownership of their land and perpetually on the edge of poverty, the Irish peasantry had no safety net. When the blight struck in 1845, it didn’t just destroy a food source; it annihilated the very foundation of their existence.

Ideology Over Humanity: The British Government’s Response

The British government’s reaction to the crisis is perhaps the most controversial and damning aspect of the famine. The response was filtered through the rigid economic doctrine of laissez-faire, a belief that the government should not interfere with the free market. This ideology, combined with a pervasive anti-Irish prejudice, proved to be a lethal combination.

Initially, the Conservative government under Prime Minister Robert Peel showed some pragmatism. He secretly imported £100,000 worth of maize (Indian corn) from America to be sold cheaply. Though unpopular and difficult to cook—earning it the name “Peel’s Brimstone”—it did prevent some starvation in the first year.

However, Peel’s government fell in 1846 and was replaced by Lord John Russell’s Whig party, who were dogmatic adherents to laissez-faire. The key figure in the administration was Charles Trevelyan, the Assistant Secretary to the Treasury. Trevelyan viewed the famine not as a humanitarian crisis to be solved, but as a divine mechanism for correcting Ireland’s perceived overpopulation and flawed character. In his own words, he saw the famine as “the sharp but effectual remedy by which the cure is likely to be effected… God grant that the generation to which this great opportunity has been offered may rightly perform its part.”

Under this ideology, the government enacted a series of disastrous policies:

- Continued Food Exports: In a cruel paradox that still incites rage today, food was being exported out of Ireland while its people starved. Throughout the famine years, vast quantities of grain, livestock, and butter were shipped to England and Europe for profit. Armed guards protected the carts and barges carrying food from the desperate and hungry, highlighting that the problem was not a lack of food in Ireland, but the inability of the poor to afford it.

- Punitive Public Works: The government established public works projects, such as building “roads to nowhere”, for starving men to earn a pittance to buy food. The work was deliberately arduous and the wages abysmal, often delayed for weeks. Many men died from exhaustion and malnutrition while working on these projects.

- The Poor Law: In 1847, the government shifted the entire cost of famine relief onto Ireland’s own system of rates and taxes, administered through workhouses. This law included the infamous “Gregory Clause”, which denied relief to anyone holding more than a quarter-acre of land. To become eligible for the workhouse, a starving family had to surrender their home and livelihood, effectively becoming permanent paupers. This led to a tidal wave of evictions, as landlords cleared their estates of tenants to avoid the tax burden.

The Human Toll: A Landscape of Death and Despair

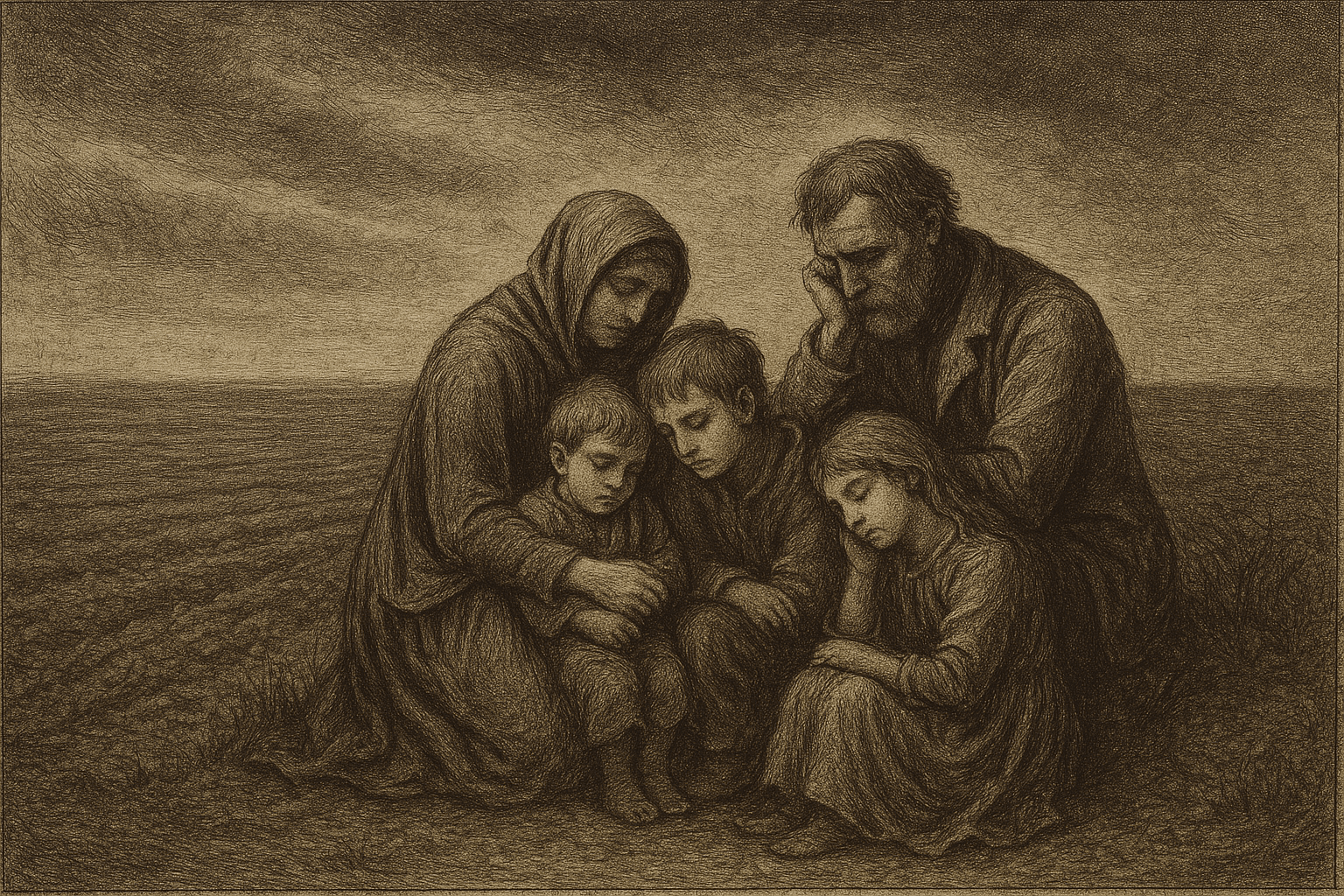

The impact on the Irish people was apocalyptic. Entire villages disappeared. Eyewitness accounts describe a silent, spectral landscape where the only sounds were the crying of hungry children and the hammering of coffins.

Death came not just from starvation, but from diseases like typhus, cholera, and dysentery, which ran rampant among the weakened population. The dead were often buried in mass graves, or “famine pits”, without ceremony. Families were torn apart as people were forced into crowded, disease-ridden workhouses or made the desperate choice to emigrate.

This led to the second great tragedy of the famine: mass emigration. Over a million people boarded ships for North America and Britain between 1845 and 1855. These journeys were perilous. The vessels, often dangerously overcrowded and unsanitary, became known as “coffin ships.” It’s estimated that tens of thousands died during the Atlantic crossing from disease and starvation, their bodies cast into the sea.

A Legacy of Ruin and Remembrance

By the time the blight receded in the early 1850s, Ireland was changed forever. The population had been reduced by nearly 25% through death and emigration, a demographic shock from which the island has never fully recovered. The Irish language, already in decline, was nearly wiped out, as the Famine hit its rural heartlands hardest.

The Great Famine was a defining moment in Irish history. It shattered any remaining trust in British rule and sowed the seeds of revolutionary nationalism that would culminate in the fight for independence. It also created the vast Irish diaspora, spreading a legacy of loss and resentment across the globe.

To remember An Gorta Mór is to remember that famines are rarely just natural disasters. They are often complex failures of politics, economics, and human empathy. The blight may have been an act of nature, but the Great Hunger was an avoidable catastrophe, a grim lesson in how ideology, when divorced from humanity, can lead to devastation on an almost unimaginable scale.