In an age before viral tweets and online backlash, one German company managed to create a public relations catastrophe of such epic proportions that it led to riots, soured diplomatic relations, and ultimately destroyed the company itself. Their crime? Inventing a meat-flavored bouillon cube and trying to sell it to the world.

A Scientific Marvel in Search of a Meal

Our story begins in Stuttgart with Gelmer & Söhne, a respectable chemical and dye manufacturer. In 1901, the company’s patriarch, Dr. Klaus Gelmer, accidentally stumbled upon a revolutionary food preservation technique. By boiling down beef broth and a secret blend of salts and flavor enhancers, he created a small, hard, brown cube that, when dissolved in hot water, produced a savory, meat-like broth. He called it Fleischkraft, or “Meat Power.”

It was a triumph of German efficiency and food science. A shelf-stable, portable source of nourishment! The problem was, nobody knew what to do with it. It was a solution without a problem. Early attempts to market it to hospitals as a “restorative tonic for the infirm” failed miserably, with patients complaining about the salty, unnatural taste.

Enter Herr Gunther Schmidt, a brash young marketing director hired to turn Fleischkraft’s fortunes around. Schmidt, inspired by the aggressive advertising tactics emerging from the United States, decided that caution was for losers. He believed Fleischkraft wasn’t just a soup base; it was the future. His new slogan was as bold as it was confusing: “Ein Steak in deiner Tasche!” – “A Steak in Your Pocket!”

The Campaign of Chaos

Schmidt’s marketing plan wasn’t just aggressive; it was a full-frontal assault on the senses of the German public. His three-pronged strategy would become a masterclass in how to alienate every potential customer simultaneously.

1. The Unsolicited Cube Drop

First, Schmidt initiated a massive direct-mail campaign. Millions of Germans began finding unsolicited Fleischkraft cubes in their postboxes, on their doorsteps, and tucked into their newspapers. With minimal instruction—just a stark “Boil and Enjoy!”—most people were bewildered. What was this strange, smelly brown rock? Was it soap? A firestarter? A strange new type of candy? Horror stories emerged of children trying to lick them and men trying to polish their boots with them.

2. Pseudo-Scientific Hysteria

Next, advertisements flooded newspapers, claiming outlandish “scientific” benefits. Fleischkraft, the ads proclaimed, could “increase Teutonic vigor by 37%”, “align the body’s humors”, and even “promote patriotic sentiment.” These vague, bombastic claims were met with ridicule from the scientific community and deep suspicion from a public that was already wary of the mystery cubes littering their homes.

3. The Public “Soup” Demonstrations

The campaign’s disastrous climax came with a series of public demonstrations in Germany’s major cities. Schmidt’s vision was grandiose: enormous vats of free, nourishing soup for the masses, proving the miracle of Fleischkraft. The reality was a logistical nightmare. The “soup” was often little more than tepid, overly salted brown water. The crowds, lured by promises of a “feast of strength”, were massive and hungry. The soup ran out in minutes.

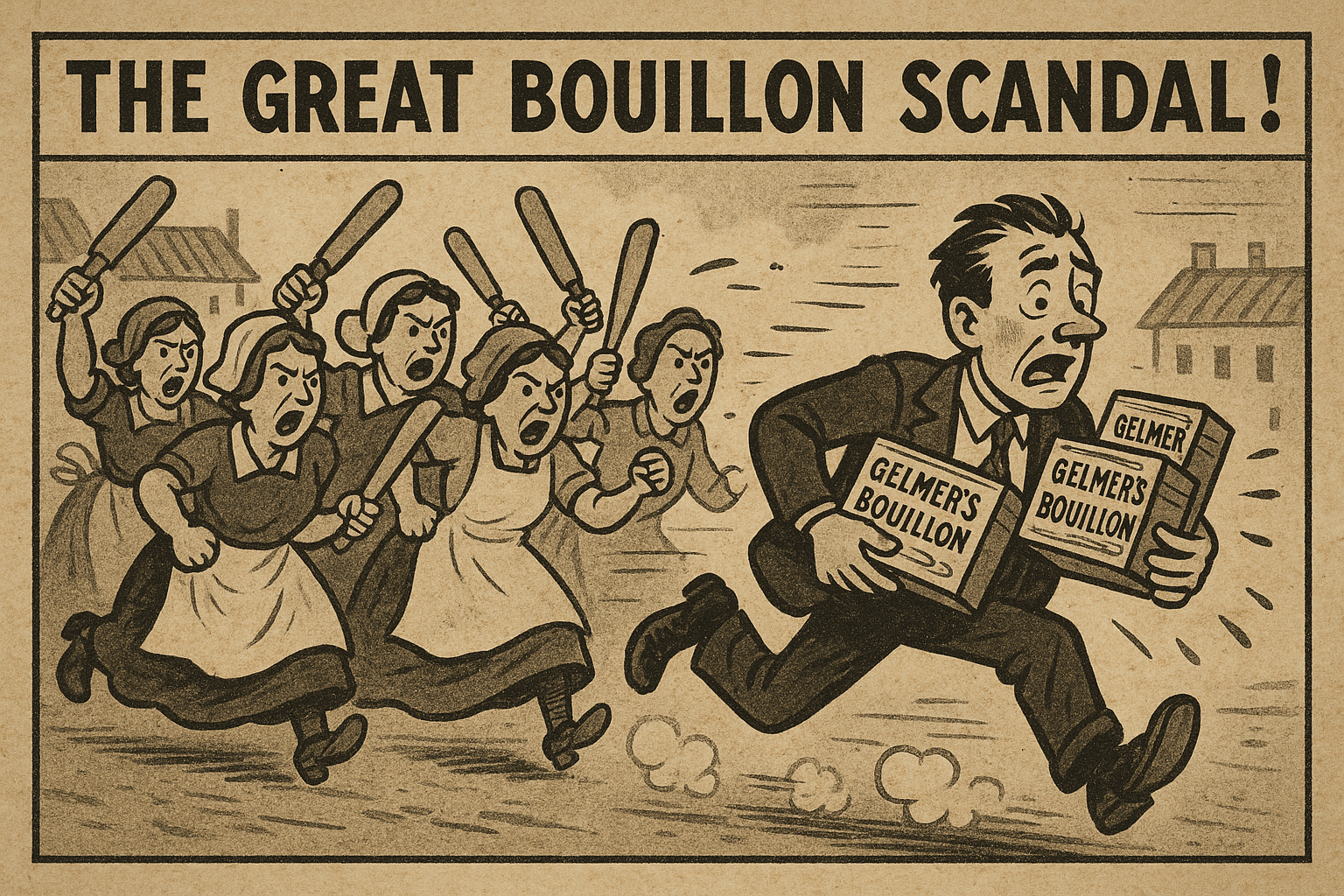

The Berlin Bouillon Riot

The breaking point came on a chilly afternoon in October 1902 in Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz. Thousands of workers, families, and curious onlookers gathered for Gelmer’s promised “soup festival.” When the meager supply vanished almost instantly, the mood turned sour. The disappointed crowd started to chant, “Where’s the steak?”

Someone threw a soggy bread roll at the panicked Gelmer representatives. In a moment of sheer marketing-induced madness, a company man threw a handful of hard Fleischkraft cubes back into the crowd. That’s when all hell broke loose. The crowd began pelting the stage with anything they could find. The police were called in to disperse a full-blown riot, sparked not by politics or poverty, but by terrible soup. The press had a field day. Headlines screamed: “BEEF-CUBE BATTLE IN BERLIN!” and “GELMER’S GOULASH GIVES GENDARMES GRIEF!”

An International Incident in a Bouillon Cube

As if rioting citizens weren’t bad enough, Schmidt’s ambition had crossed borders. In a bid to crack the French market, the “A Steak in Your Pocket!” slogan was poorly translated into “Le Bœuf dans Votre Pantalon”—”The Beef in Your Trousers.” This was widely interpreted in France, Germany’s long-standing rival, as a vulgar and deeply insulting double entendre.

French newspapers ran satirical cartoons of Kaiser Wilhelm II menacing the French figure of Marianne with a sausage. The French foreign ministry lodged a formal, if bemused, complaint about the “uncouth German advertising.” In Britain, Punch magazine gleefully depicted stout German soldiers trying to dissolve bouillon cubes in their afternoon tea. The Gelmer company had managed to become an international laughingstock.

The Collapse and the Lessons Learned

The end for Gelmer & Söhne was swift. The combination of public ridicule, financial ruin from the costly campaign, and diplomatic embarrassment was a fatal blow. Sales, which had never been good, evaporated entirely. No one wanted to be associated with the “riot cube.” By the end of 1902, the company declared bankruptcy. Dr. Gelmer, a broken man, abandoned food science forever and returned to the quiet, predictable world of industrial dyes.

The Gelmer Fiasco, though hilarious, remains a powerful parable for the modern age. It serves as a potent reminder of a few timeless truths:

- Know your audience. People don’t want mysterious brown cubes; they want food they understand.

- Don’t over-promise and under-deliver. If you promise a “feast of strength”, you had better provide more than salty water.

- Context is everything. A slogan that works in one language can become a diplomatic incident in another.

So, the next time you see a marketing campaign that seems a little too aggressive or a product with claims that are a little too wild, remember the Gelmer Fiasco of 1902. Remember the men who promised a steak in every pocket and delivered only chaos in a cube.