Imagine the Sahara Desert. Not the romantic image of rolling dunes at sunset, but the reality: a vast, hyper-arid sea of sand and rock, one of the most hostile environments on Earth. Now, imagine a thriving kingdom in its very heart. A civilization that built cities, cultivated fields of grain and groves of date palms, and commanded armies powerful enough to challenge the Roman Empire. This was no mirage. This was the realm of the Garamantes.

For nearly a thousand years, from roughly 500 BCE to 500 CE, the Garamantes were the undisputed masters of the Sahara. From their capital city of Garama in the Fezzan region of modern-day Libya, they engineered a sophisticated society that stands as a testament to human ingenuity in the face of impossible odds. Their secret weapon wasn’t a mythical power or a unique metal, but something far more precious in the desert: water, and the genius to control it.

Engineering an Oasis Empire: The Foggara System

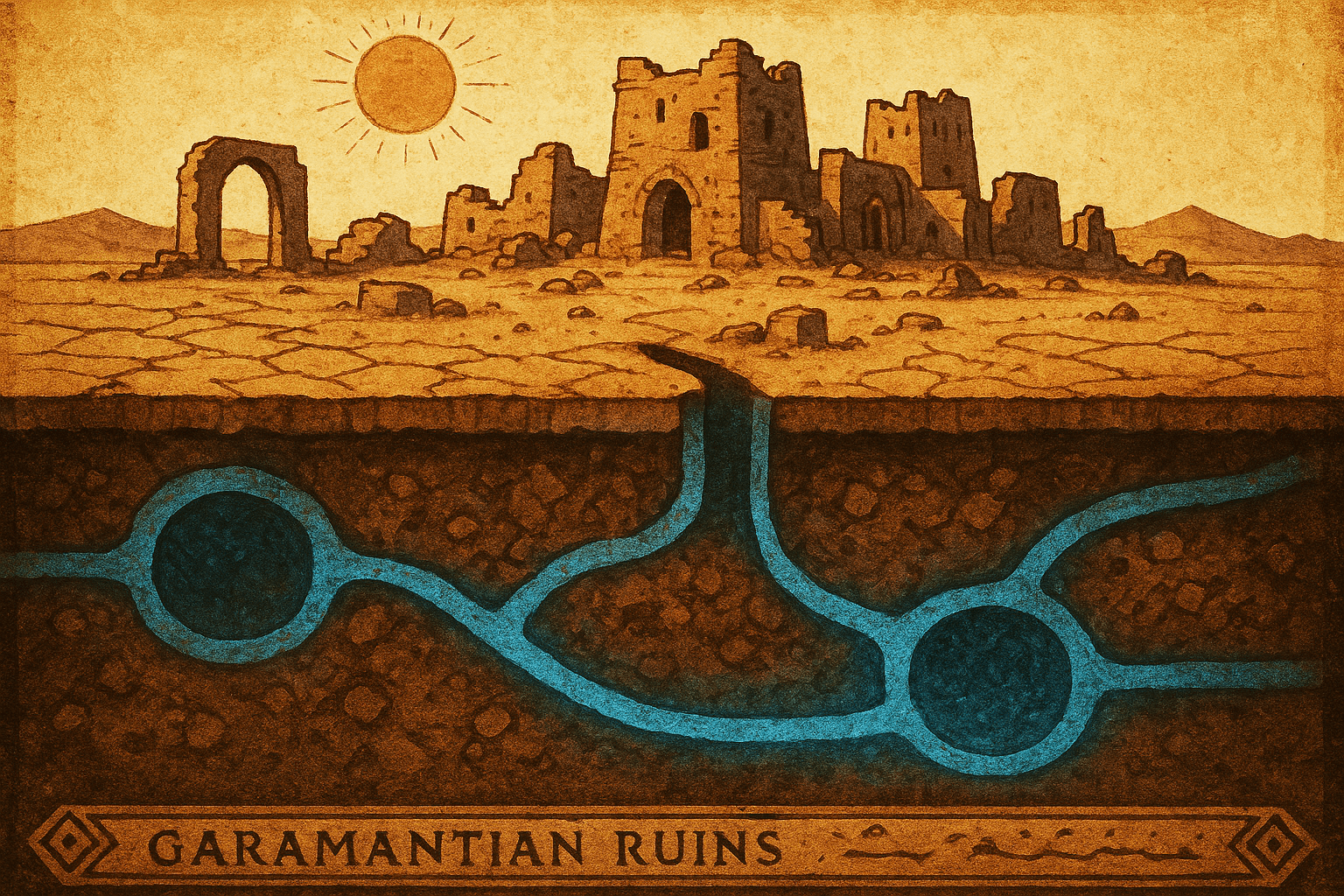

The key to Garamantian survival and prosperity lay buried deep beneath the sand. They lived atop a massive, non-renewable reservoir of “fossil” water, trapped underground for millennia. The challenge was getting it to the surface in a climate where any exposed water would evaporate in an instant.

Their solution was a marvel of ancient hydro-engineering: the foggara. Known elsewhere as qanats, a foggara is a gently sloping underground tunnel, hand-dug through rock and sand, that taps into the subterranean water table. These tunnels, often running for several kilometers, would channel the water using only gravity, delivering it to surface canals that irrigated their fields.

The brilliance of the foggara system was twofold:

- It minimized evaporation: By keeping the water underground for almost its entire journey, the Garamantes prevented the relentless sun from stealing their most vital resource.

- It was gravity-powered: Once constructed, the system required no energy to operate, providing a constant, reliable flow of water to their settlements.

The scale of this undertaking is staggering. Archaeologists have identified over 600 foggara systems in the Garamantian heartland, comprising thousands of kilometers of underground tunnels. Vertical shafts, dug every 10-20 meters along the tunnel’s length, provided ventilation and access for maintenance. The effort to create this subterranean network, dug with simple hand tools, represents millions of hours of labor. It allowed them to support a population density completely unheard of in the Sahara, turning a barren landscape into a breadbasket that could sustain cities and armies.

A Kingdom of Trade and War

With their agricultural base secured, the Garamantes became a pivotal node in the burgeoning trans-Saharan trade routes. They were the middlemen connecting sub-Saharan Africa with the Mediterranean world of the Roman Empire. Their caravans, likely using camels in later periods, controlled a lucrative and dangerous superhighway of commerce.

Goods flowing north to Rome included:

- Gold, ivory, and ebony from the African interior

- Exotic animals destined for the Roman arenas

- Precious carnelian beads, a Garamantian specialty

- Salt, a crucial commodity, mined from desert deposits

- Enslaved people captured in raids

In return, Roman luxury goods flowed south: fine pottery, glass vessels, wine, olive oil, and textiles. This trade made the Garamantian elite incredibly wealthy and their kingdom a strategic power that Rome could not ignore.

Chariots in the Sand: A Thorn in Rome’s Side

The Garamantes were not merely passive traders. The Greek historian Herodotus described them as a “very great nation” who hunted “the Ethiopian cave-dwellers” using four-horse chariots. While this imagery might be slightly romanticized, it speaks to their military prowess. They were expert desert warriors who frequently raided Roman settlements along the North African coast (the Limes Tripolitanus), plundering them for goods and captives.

Rome responded with force. In 21 BCE, the Roman general Lucius Cornelius Balbus led a punitive expedition deep into the Fezzan, capturing Garama and other towns. This was a show of force, but it didn’t subdue the Garamantes for long. They remained a persistent threat on Rome’s southern frontier, prompting further campaigns, including one by the future emperor Septimius Severus. This complex relationship of raid, trade, and reprisal defined their existence on the edge of the world’s greatest empire.

The Fall of a Desert Kingdom

So what happened to this formidable desert civilization? How did a kingdom that thrived for a millennium seemingly vanish into the sands of time? The answer, ironically, lies in the very system that gave them life.

The foggara system tapped into a finite resource. The fossil water they relied on was not being replenished by rainfall. Over centuries of intensive use, the water table inexorably dropped. As it fell below the level of their tunnel intakes, the foggara began to dry up one by one. Their agricultural foundation, the bedrock of their society, crumbled beneath them.

This environmental collapse was likely compounded by other factors. The decline and eventual fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE crippled their main trading partner, shattering their economy. Political instability and pressure from other nomadic groups would have exploited their growing weakness. By the 6th or 7th century CE, the Garamantian kingdom had faded away, its cities abandoned to the encroaching desert.

Legacy of the Sand Masters

For centuries, the Garamantes were little more than a whisper in the works of classical authors like Herodotus and Pliny. But modern archaeology has resurrected their story, revealing the true scale of their achievements. The ruins of Garama and the ghostly outlines of thousands of foggara shafts dotting the Libyan landscape paint a clear picture of a complex, powerful, and innovative society.

The Garamantes are a potent reminder that history is full of remarkable civilizations that flourished in the most unexpected places. They mastered the Sahara, building an empire on water and ingenuity. Their story is not just one of a lost kingdom, but a cautionary tale about the sustainability of resources, and an awe-inspiring saga of humanity’s ability to adapt and conquer the most extreme environments on the planet.