****

In the quiet English countryside of Cambridgeshire, just off the old Great North Road, lies a field marked by a simple stone monument. To the casual observer, it’s just another patch of farmland. But beneath the soil lie the ghosts of a revolutionary and brutal chapter in world history: the foundations of Norman Cross, the world’s first purpose-built prisoner-of-war camp.

During the long and bloody wars against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France (1793-1815), Britain faced an unprecedented problem. Tens of thousands of enemy combatants, mostly French sailors and soldiers, were being captured. The existing system of cramming them into repurposed castles or the notoriously foul, disease-ridden prison hulks—decommissioned warships moored in estuaries—was inhumane, inefficient, and a constant security risk. A new, radical solution was needed.

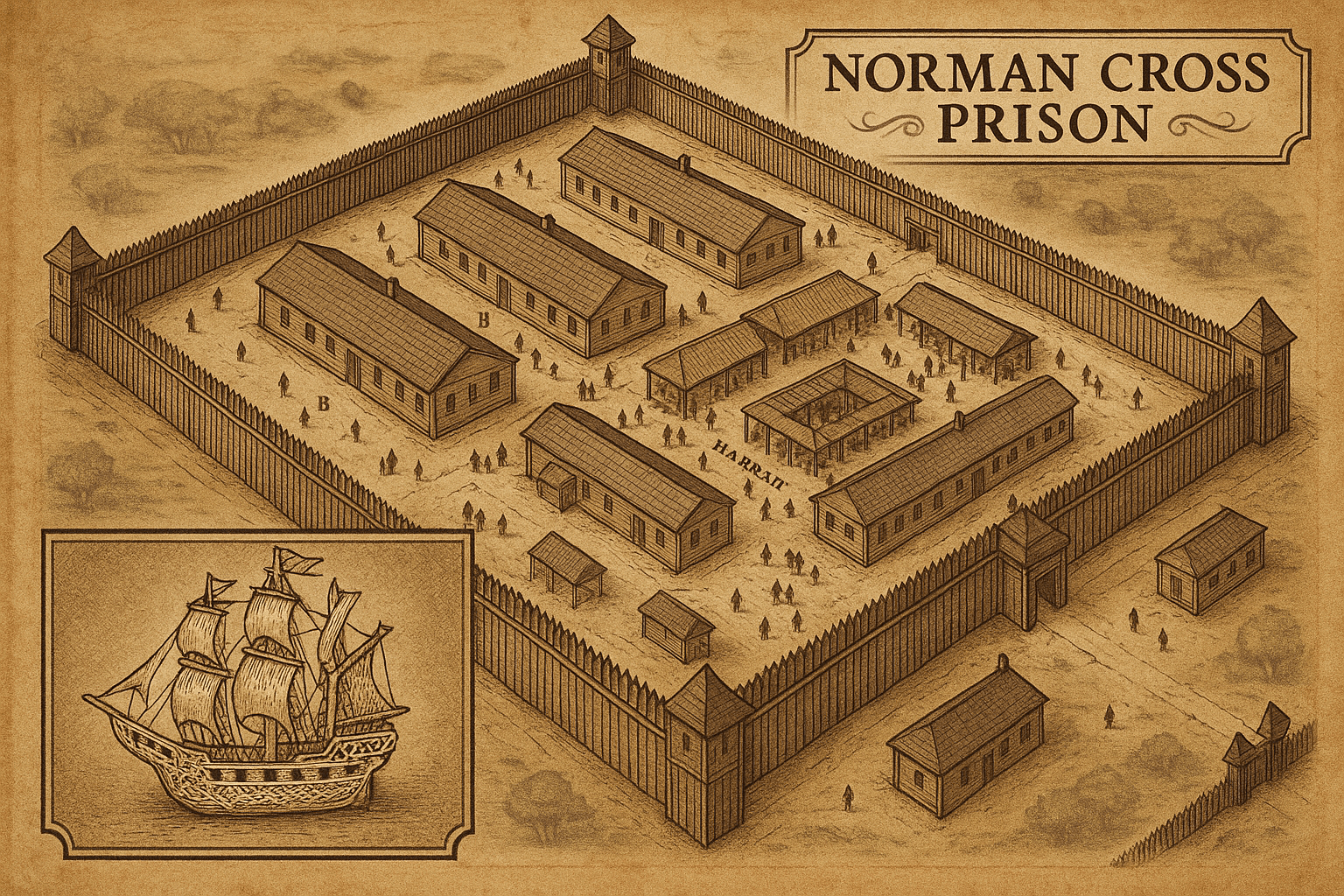

A Sprawling Wooden City

In 1796, the British government’s Transport Board made a decisive choice. They would construct a massive, dedicated depot designed specifically to hold prisoners of war. The site chosen was Norman Cross, strategically located on a major transport route, close to London, and near the freshwater sources of the fens. Construction began at a frantic pace, and within just six months, a sprawling wooden city had risen from the fields.

The scale of Norman Cross was staggering. It covered around 40 acres and was designed to hold up to 7,000 men. The layout was a model of grim efficiency, designed for control and surveillance:

- The camp was divided into four main quadrangles, each surrounded by a 15-foot high wooden palisade.

- Within each quadrangle were sixteen two-story wooden barracks, housing the prisoners in cramped conditions on hammocks or beds of straw.

- A wide central road, known as “Norman Way”, ran through the camp, separating the quadrangles and providing a clear line of sight for the guards.

- Surrounding the entire perimeter was another massive palisade fence, punctuated by guard towers armed with cannons.

- Separate barracks housed the British garrison of soldiers, the camp commandant, officers, a surgeon, and other administrators.

Norman Cross was more than just a prison; it was a small, self-contained town. It had its own hospital, a bakehouse, a well system, and a marketplace. For nearly two decades, this temporary city was one of the most populous places in the region, a holding pen for a generation of men caught on the losing side of a global conflict.

Life Behind the Palisade

For the thousands of French, Dutch, and Danish prisoners who passed through its gates, life at Norman Cross was a relentless battle against boredom, hunger, and despair. The daily routine was monotonous: morning roll call, the distribution of meager rations, and long hours with little to do. Rations officially consisted of bread, beef, and vegetables, but corruption was rife. Contractors often supplied poor-quality food, and the prisoners frequently complained of being underfed.

Disease was a constant threat. With so many men living in close quarters, outbreaks of typhus and pneumonia were common, though the purpose-built hospital—a significant innovation for its time—helped mitigate the worst of the epidemics that plagued the prison hulks. Still, hundreds of men died and were buried in the nearby churchyard of St. Mary the Virgin in Yaxley.

Despite the grim circumstances, the prisoners found ways to create their own society. They organised gambling rings, staged theatrical productions, held fencing matches, and even ran schools where literate men taught their comrades to read and write. The most significant activity, however, grew not from a desire for entertainment, but from the desperate need to survive.

Art from Adversity: The Norman Cross Crafts

The prisoners of Norman Cross had almost no money, but they had two crucial resources: time and ingenuity. To supplement their meager rations or purchase small comforts, they developed a remarkable cottage industry, creating intricate and beautiful objects from the most humble of materials. These items were sold at a daily market held at the camp gates, where local civilians gathered to buy these unique “curiosities.”

The craftsmanship that emerged from Norman Cross is considered some of the finest prisoner-of-war art ever produced. The main materials included:

- Bone: Leftovers from their meat rations were boiled, cleaned, and meticulously carved.

- Straw: Taken from their mattresses, it was split, flattened, and dyed with colours made from natural pigments or scraps of cloth.

- Wood: Scraps from camp repairs or old crates were fashioned into various objects.

- Human Hair: Woven to create delicate pictures or chains.

Using makeshift tools—often little more than sharpened nails or pieces of glass—the prisoners created a breathtaking array of items. Most famous among them were the astonishingly detailed model ships. These were not simple toys; they were miniature masterpieces of engineering, complete with full rigging made from human hair, tiny cannons, and planked hulls, often crafted entirely from bone. Some models, like those of the French warship Vengeur du Peuple, became iconic examples of this art form.

Another specialty was straw marquetry. Prisoners would painstakingly glue dyed strips of straw onto wooden boxes, picture frames, and tea caddies, creating vibrant geometric patterns, pastoral scenes, or Masonic symbols. They also carved domino and chess sets, spinning jennies (miniature working models of textile machines), automata, and even grisly but popular models of the guillotine.

The End of an Era and a Lasting Legacy

With Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo in 1815, the prisoners of Norman Cross were finally repatriated. The camp was no longer needed, and by 1816, its wooden structures were auctioned off and dismantled. The land was returned to agriculture, and for nearly a century, the story of the world’s first POW camp faded into local folklore.

In 1914, a memorial featuring the original Imperial Eagle from the camp gates was erected on the site, a permanent reminder of the thousands who lived and died there. Today, the legacy of Norman Cross survives primarily through the incredible objects its inmates created. Housed in museums like the Peterborough Museum and Art Gallery, these bone ships and straw boxes are more than just historical artifacts. They are powerful testaments to human resilience, creativity, and the irrepressible will to find beauty and purpose in the darkest of circumstances.

The field at Norman Cross may be quiet now, but it stands as a monument to a pioneering, brutal, and ultimately human experiment in the history of warfare.

**