In the summer of 1783, a strange and terrifying phenomenon settled over Europe. A persistent, acrid haze shrouded the landscape, dimming the sun and casting an eerie, reddish light. The air smelled of sulfur, crops withered in the fields, and people began to fall ill and die from mysterious respiratory ailments. In an age before global communication, no one knew the cause. Was it a divine curse? An atmospheric anomaly? The truth was far more dramatic, originating hundreds of miles away in the remote, icy wilderness of Iceland.

This was the Laki eruption, or Skaftáreldar (“Skaftá River Fires”), an event largely erased from popular memory but one that stands as a stark reminder of how a single geological event can trigger a global catastrophe, with social and political consequences that would echo for years.

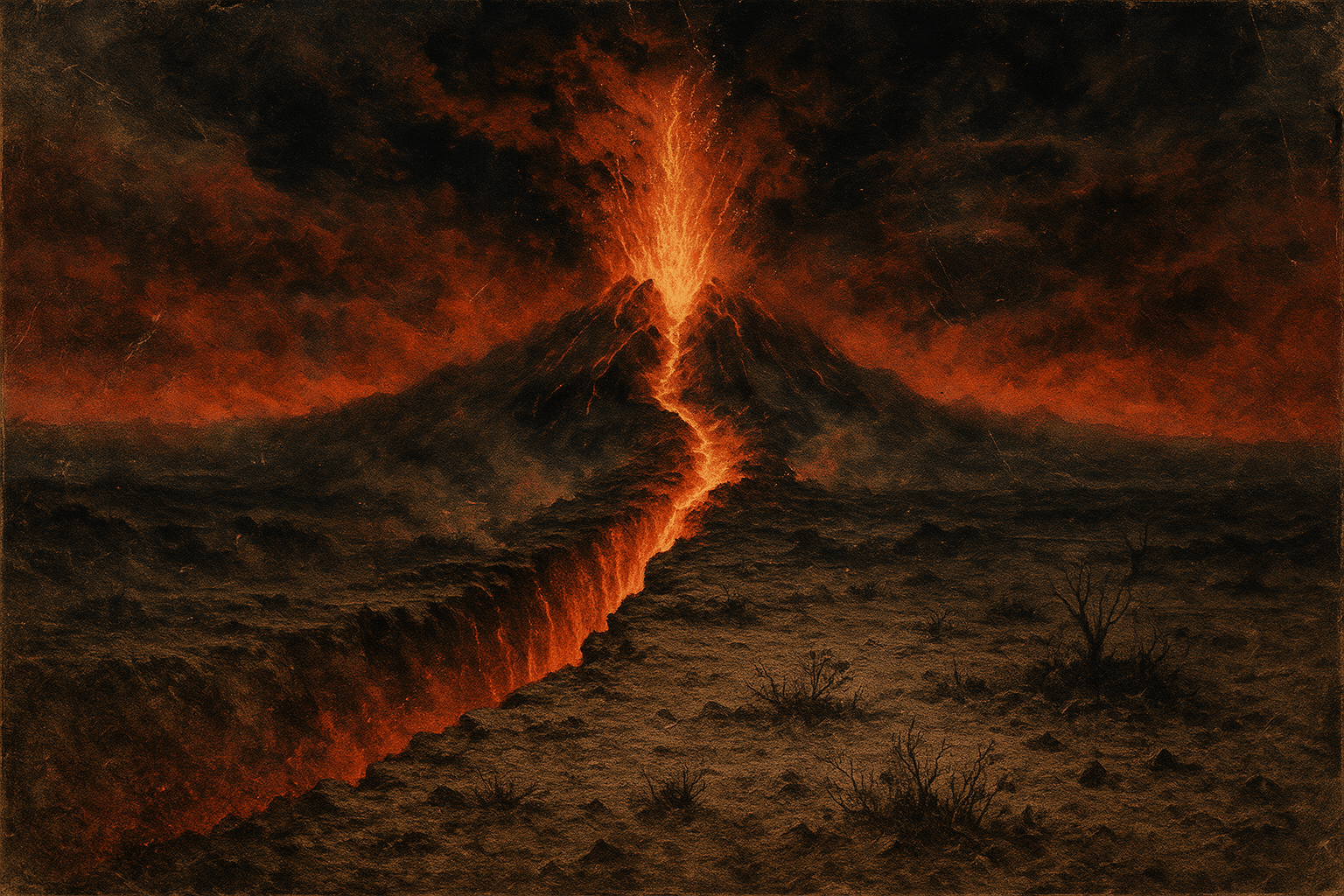

Fire, Gas, and a Fissure of Doom

The disaster began on June 8, 1783. This was no ordinary, cone-shaped volcano. Instead, the earth split open along a 17-mile (27-kilometer) long fissure, part of the Grímsvötn volcanic system. Over the next eight months, a series of 130 craters along this crack, known as the Laki fissure, spewed hellfire onto the Icelandic landscape.

The sheer volume of lava was staggering—an estimated 14 cubic kilometers flowed out, enough to cover a city the size of Boston in a layer over 650 feet deep. But the lava, while devastating locally, was not the primary agent of global chaos. The real killer was the gas. Laki’s eruption released an estimated 120 million tonnes of sulfur dioxide (SO₂) into the atmosphere. To put that in perspective, it’s roughly three times the total industrial SO₂ emissions in all of Europe in 2006.

For Iceland, the effect was apocalyptic. The period became known as the Móðuharðindin, or “The Hardships of the Mist.” The massive release of sulfur dioxide and hydrogen fluoride created a poisonous acid rain that fell across the island. The fluoride contaminated the grass, leading to dental and skeletal fluorosis in livestock. Around 80% of sheep, 50% of cattle, and 50% of horses perished. Without livestock, the island’s population faced a catastrophic famine. By the time the eruption ended in February 1784, approximately 10,000 Icelanders—a full quarter of the country’s population—had died.

The “Laki Haze” Spreads Across the World

As the toxic plume rose into the jet stream, it was carried southeast towards mainland Europe. By late June, the “Laki Haze” had arrived. When the sulfur dioxide mixed with water vapor in the atmosphere, it formed tiny droplets of sulfuric acid. This created a thick, persistent “dry fog” that did not dissipate with the morning sun.

Contemporary accounts paint a terrifying picture. In Paris, the American statesman and scientist Benjamin Franklin noted the odd-smelling fog and was one of the first to hypothesize its volcanic origin, writing:

“During several of the summer months of the year 1783, when the effect of the sun’s rays to heat the earth in these northern regions should have been greatest, there existed a constant fog over all Europe, and a great part of North America. This fog was of a permanent nature; it was dry, and the rays of the sun seemed to have little effect towards dissipating it… of course their summer effect in heating the Earth was exceedingly diminished.”

The health impacts were severe. The acid aerosols irritated the lungs, leading to a surge in deaths from respiratory illness, particularly among the elderly and outdoor laborers. The United Kingdom alone is estimated to have suffered around 23,000 excess deaths during the summer and autumn of 1783. Ships lost their way in the fog-choked English Channel, and crops across the continent failed due to the acid rain and reduced sunlight.

A Global Climatic Disruption

The eruption’s impact was not confined to Europe. The massive sulfuric acid cloud in the stratosphere acted like a veil, reflecting sunlight back into space and causing a significant drop in Northern Hemisphere temperatures. This triggered a “volcanic winter.”

The winter of 1784 was one of the longest and most severe on record in North America. The Mississippi River reportedly froze all the way down to New Orleans, and ice floated in the Gulf of Mexico. But the climatic chain reaction was even more devastating elsewhere:

- Africa: The cooling of the Northern Hemisphere disrupted the atmospheric circulation patterns that drive the African monsoon. The rains failed, causing a severe drought in the Sahel and drastically reducing the flow of the Nile River. The resulting famine in Egypt killed an estimated one-sixth of its population.

- Asia: The Indian monsoon was also weakened, leading to food shortages and famine in parts of the Indian subcontinent.

An eruption in a remote corner of Iceland had directly caused famine and death on three continents.

The Volcano and the Guillotine?

Perhaps the most debated long-term consequence of the Laki eruption is its potential role in triggering the French Revolution. While no single event causes a revolution, Laki’s climate-altering effects may have been the final push that sent French society tumbling into chaos.

The extreme weather patterns unleashed by Laki—scorching summers, hailstorms, and brutal winters—led to a series of devastatingly poor harvests in France in the years leading up to 1789. This caused severe grain shortages and sent the price of bread, the staple food for the poor, skyrocketing. Facing starvation and suffering under a regressive tax system that spared the nobility and clergy, the frustrations of the Third Estate boiled over. The economic hardship, fueled directly by Laki’s climate impact, intensified the social and political grievances that ultimately led to the storming of the Bastille.

A Lesson from a Forgotten Past

The story of Laki is a powerful, if terrifying, lesson in global interconnectedness. In the 18th century, no one could piece together the full puzzle. The famines in Egypt, the deadly fog in Britain, and the crippling harvests in France were all seen as separate, inexplicable tragedies. It took nearly two centuries of scientific advancement to connect the dots back to that fiery fissure in Iceland.

Today, as we face our own global climate challenges, Laki serves as a historical case study. It demonstrates how profoundly and rapidly our planet’s climate can be altered and how those changes can cascade through ecosystems and human societies, leading to famine, instability, and political upheaval. It is a catastrophe largely forgotten, but one whose lessons have never been more relevant.