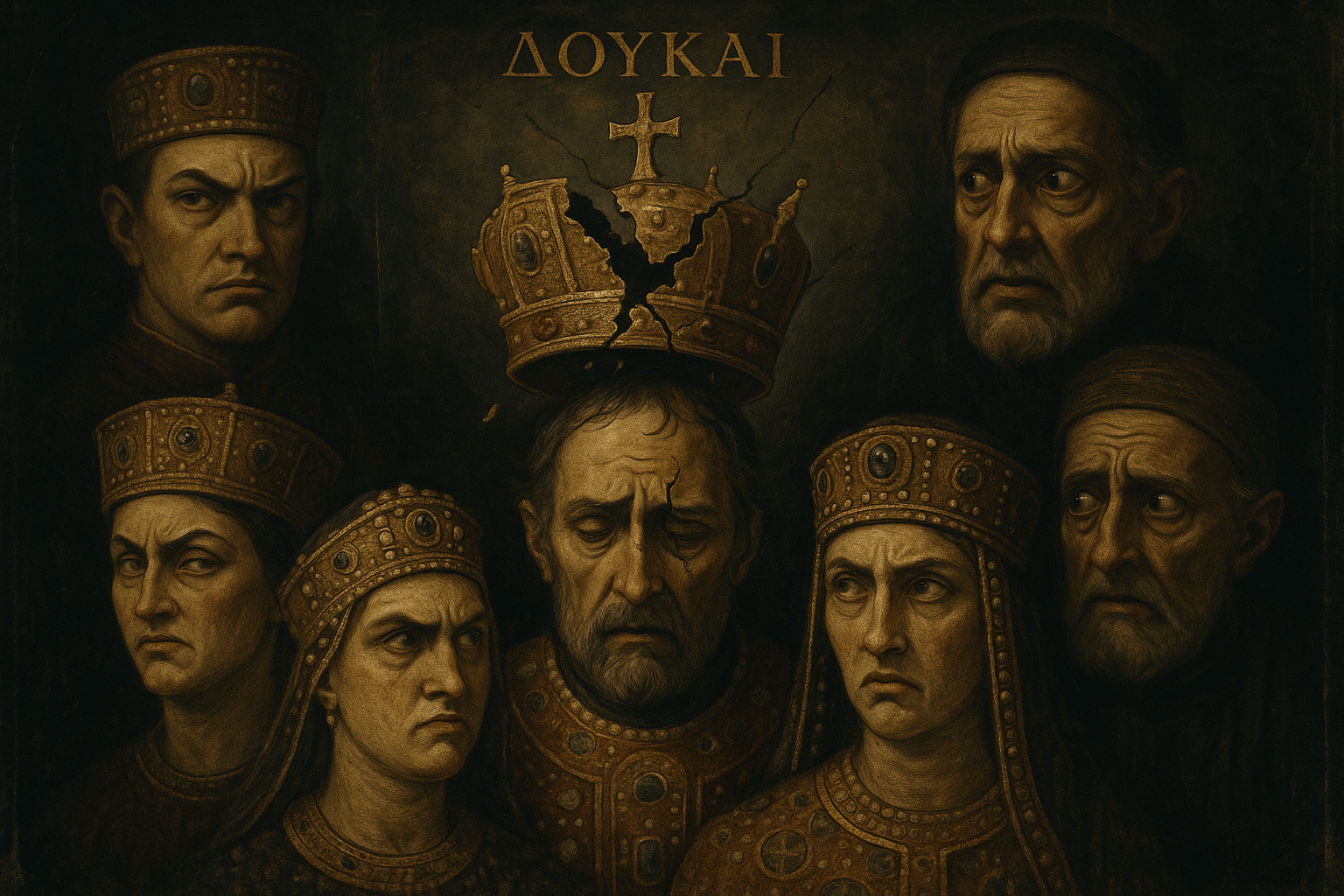

The Bureaucrat on the Throne

Our story begins not on a battlefield, but in the perfumed, ink-stained offices of the imperial bureaucracy. The founder of the dynastic tragedy was Constantine X Doukas, who ascended the throne in 1059. He was a man of the civil aristocracy, a class that valued paperwork over swordplay and budgets over military readiness. He and his faction believed the real threats to the empire were not external enemies, but powerful, over-mighty generals who might launch a coup.

Acting on this conviction, Constantine X began a systematic dismantling of the Byzantine army. He slashed military spending, disbanded experienced local militias, and replaced seasoned commanders with loyal (and often incompetent) civilian cronies. All the while, a new and formidable power was rising in the East: the Seljuk Turks. As Turkish raiders began to probe and pillage the empire’s Anatolian heartland—the primary source of its soldiers and food—Constantine X and his court remained dangerously complacent, more concerned with balancing the budget than defending the borders.

When Constantine died in 1067, he left the throne to his young son, Michael VII, under the regency of his wife, the Empress Eudokia Makrembolitissa. He also left an empire teetering on the brink of military catastrophe. The “curse” had begun to take root.

A Desperate Gamble and a Fateful Battle

Faced with an escalating crisis in the East, the Empress Eudokia made a pragmatic choice. She broke the oath Constantine had forced upon her—never to remarry—and chose a husband from the military aristocracy: the capable general Romanos Diogenes. As Romanos IV, he took the throne in 1068, determined to push the Seljuk Turks out of Anatolia once and for all.

This was anathema to the Doukas clan. The powerful Caesar, John Doukas (brother of the late Constantine X), and his sons saw Romanos as a usurper, an obstacle to the rightful rule of their young nephew, Michael VII. Though they were forced to serve him, their loyalty was a fragile veneer hiding a core of resentment and ambition. Romanos, aware of their plotting, was a man surrounded by enemies both in front of and behind him.

In August 1071, Romanos IV led a massive imperial army to confront the Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan near the town of Manzikert in eastern Anatolia. This was to be the decisive battle to save the empire. Romanos, a brave if somewhat reckless commander, placed one of the Doukas family members, Andronikos Doukas, in command of the vital rear guard and reserve forces.

It was a fatal mistake.

The Betrayal at Manzikert

The Battle of Manzikert was a close-run affair until a critical moment. As Romanos, believing the battle won for the day, signaled a tactical retreat to camp, chaos erupted. Andronikos Doukas, seeing his opportunity, deliberately spread a rumor that the Emperor had fallen. He then turned his entire reserve force around and fled the battlefield, abandoning his emperor and the main army.

This act of calculated treachery shattered the Byzantine line. Panic spread like wildfire. Surrounded and deserted, Romanos IV and the core of the Byzantine army were overwhelmed. The Emperor was captured—an unprecedented humiliation. The Battle of Manzikert was not merely a defeat; it was an annihilation, and it was engineered by the Doukas family’s lust for power.

The “curse” had just claimed its biggest victim: the Anatolian heartland. With the army destroyed, there was nothing to stop the flood of Turkish migration into the region. The Doukai had just sacrificed the empire’s most valuable province to reclaim the throne.

The Price of Power: A Hollow Crown

With Romanos IV a captive, the Caesar John Doukas moved swiftly. He declared Romanos deposed and placed his nephew, Michael VII Doukas, on the throne as sole ruler. When the Seljuks, in a surprising act of chivalry, released Romanos, the Doukai had him hunted down, brutally blinded with a hot iron, and exiled to a monastery, where he soon died from his wounds. They had their throne back.

But it was a poisoned chalice. The reign of Michael VII (1071-1078) was an unmitigated disaster. He was an academic and an intellectual, utterly unsuited to ruling a crumbling empire. His incompetence earned him the nickname Parapinakes, or “Minus-a-Quarter”, because during a famine, his ministers famously sold wheat for only three-quarters of the standard measure.

Under his watch, the consequences of Manzikert became terrifyingly clear. Anatolia was lost for good. The empire’s economy collapsed, its currency was devalued, and civil wars erupted as rival generals and adventurers tried to seize power. The Doukas family had achieved their ultimate goal, only to preside over the wreckage they had created.

In 1078, Michael VII was forced to abdicate and retreat to a monastery, bringing the direct Doukas imperial line to an ignominious end. The family who put their own power above the state had lost both.

The “Curse” Re-examined: Ambition Over Empire

Was there a supernatural curse on the House of Doukas? Of course not. But their legacy reads like a Greek tragedy, a story of hubris leading to inevitable downfall. The “curse” was a historical pattern of self-sabotage driven by a few key factors:

- Myopic Ambition: The Doukai were consumed by the desire for the throne, failing to see that their actions were destroying the very empire they wished to rule.

- Civil-Military Divide: Their deep-seated distrust of the military led to the neglect that made disasters like Manzikert possible. They weakened the shield of the empire out of fear it might be turned against them.

- The Ultimate Betrayal: At Manzikert, they made an unforgivable choice: they prioritized family power over imperial survival. This single act of treachery is the centerpiece of their cursed legacy.

The Doukas family did not vanish; their name and bloodline continued, often weaving through the courts of later dynasties like the Komnenoi and the Angeloi. But their moment at the pinnacle of power in the 11th century remains a dark chapter in Byzantine history—a stark reminder that the greatest threat to an empire can often come not from its external enemies, but from the corrosive ambition festering within its own gilded halls.