From Allies to Subscribers: The Birth of the League

Our story begins in 478 BCE, in the smoky aftermath of the Greco-Persian Wars. The mighty Persian Empire had been repelled, thanks in large part to Athenian naval power at the Battle of Salamis and Spartan grit at Plataea. Though Xerxes’ invasion was defeated, Persia still controlled many Greek city-states in Ionia (modern-day western Turkey) and the Aegean islands. The threat lingered.

Fearing a Persian return and eager to liberate their fellow Greeks, a coalition of city-states met on the sacred island of Delos. They formed a voluntary military alliance, the Delian League, with two clear goals:

- Free the Greeks still under Persian rule.

- Secure the Aegean and seek reparations from Persia for the destruction of the wars.

Sparta, the preeminent land power, was initially offered leadership but politely declined. Uncomfortable with long-term overseas commitments, they retreated into their Peloponnesian shell. Athens, with its powerful navy and reputation as the saviors of Greece, was the natural and eager choice to lead. The initial arrangement was fair. Members could contribute one of two things to the common cause: fully-manned warships (triremes) or a monetary payment called the phoros. This treasure was kept in the league’s neutral treasury on Delos, home to a famous temple of Apollo.

Ships to Silver: The Critical Shift

In the early years, the league was a roaring success. Under the brilliant Athenian general Cimon, league forces drove the Persians out of an ever-increasing number of cities. But a subtle and critical change was starting to take place. For many smaller city-states, building, maintaining, and crewing a state-of-the-art trireme was immensely expensive and difficult. It was far easier to just write a check to Athens and let them handle it. This was the league’s first, fatal error.

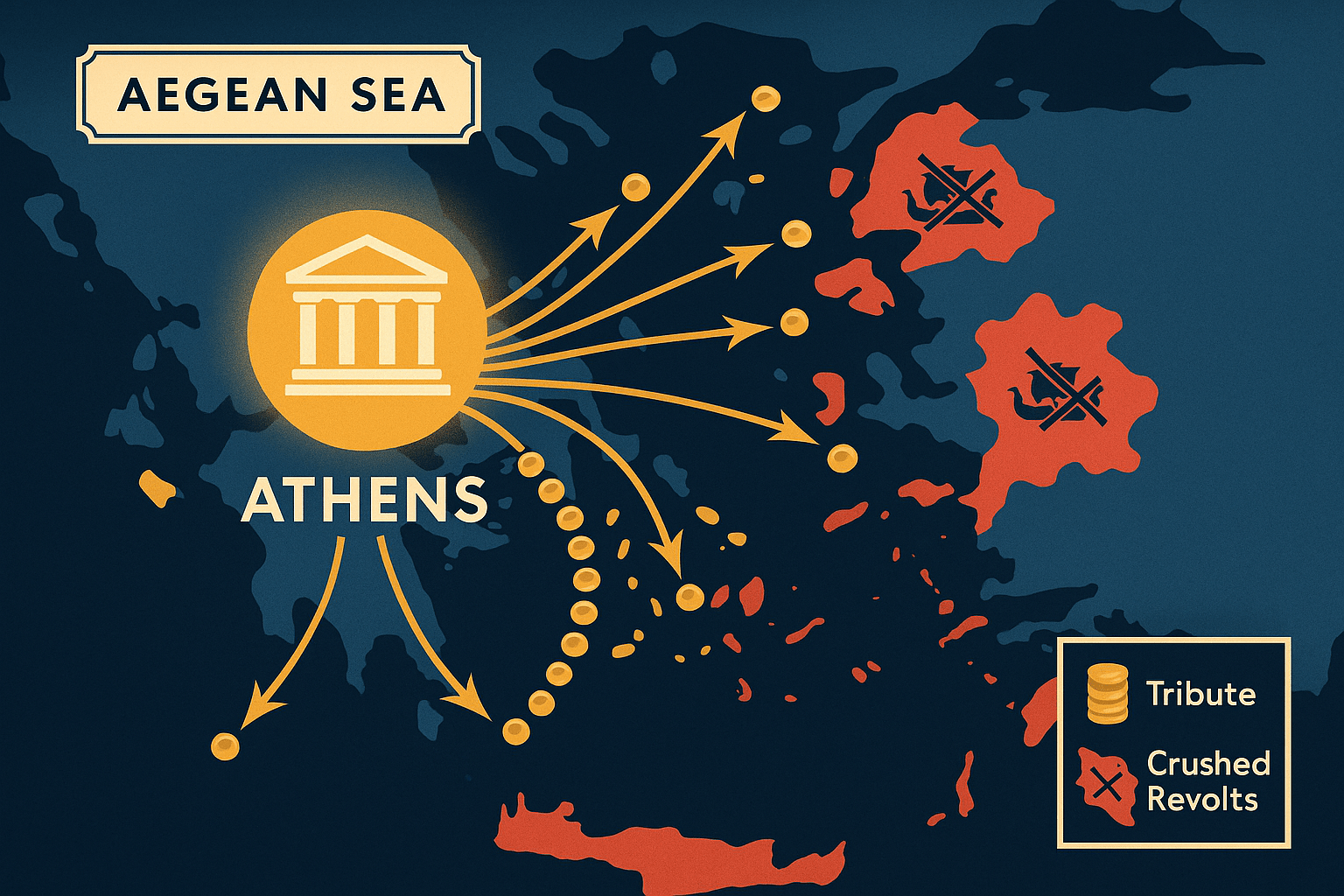

Athens was more than happy to accept the cash. They used the growing stream of phoros to expand and improve their own navy. With every passing year, Athens’ fleet grew larger and more professional, while the fleets of its allies shrank or disappeared entirely. The balance of power tilted irrevocably. The allies were no longer partners in a shared defense; they were becoming customers paying a subscription fee for protection, a service for which Athens was now the sole provider. The Persian threat, diminished by the league’s own success at battles like the Eurymedon (c. 466 BCE), became less a reason for the league’s existence and more a convenient excuse for Athens to keep collecting the payments.

Crushing Dissent: When “Ally” Means “Subject”

What happens when you try to cancel a subscription you no longer feel you need? For members of the Delian League, the answer was brutal.

The first city-state to test this was the island of Naxos around 471 BCE. Deciding they’d had enough, they attempted to secede from the league. The Athenian response was swift and merciless. They treated their “ally” as an enemy, besieged the island, and forced it to surrender. Athens confiscated Naxos’s fleet, tore down its defensive walls, and forced it to pay tribute in cash from then on. The message was chillingly clear: this alliance was not voluntary. There was no exit clause.

A few years later, the wealthy island of Thasos revolted over a dispute with Athens concerning control of gold mines. Again, Athens responded not with diplomacy but with force. After a grueling two-year siege, Thasos was subjugated, its fleet taken, and its autonomy stripped. The mask was completely off. The Delian League was no longer a defensive coalition; it was an Athenian empire, and any act of defiance was treated as a rebellion to be crushed.

The Treasury Moves to Athens: A Symbol and a Slush Fund

The final, symbolic nail in the coffin of the league’s independence came in 454 BCE. Under the pretext that the treasury on Delos was vulnerable to a Persian raid (an almost laughable excuse by this point), the Athenian statesman Pericles ordered the entire treasury to be moved to Athens. It was placed, tellingly, in the temple of Athena on the Acropolis.

Now, the allies’ tribute was paid directly to Athens, into its own coffers. The phoros was no longer a contribution to a common cause; it was a tax paid by subjects to their imperial master. Athens solidified its control by:

- Forcing allies to use Athenian coinage and systems of weights and measures.

- Establishing Athenian garrisons in disloyal or strategic cities.

- Interfering in local politics, often overthrowing oligarchies and installing democracies that would be friendly to Athens.

- Forcing legal cases to be tried in Athenian courts.

Building a Golden Age on Imperial Coin

With an enormous annual income flowing from over 200 “allied” cities, Pericles now had the funds for his ambitious vision. The Persians had sacked Athens in 480 BCE, destroying the temples on the Acropolis. Pericles argued that a magnificent rebuilding program was necessary to honor the gods and celebrate Athens’ glory. His political rivals were aghast, accusing him of “gilding and bedizening the city like a harlot, with the money that was contributed by the Hellenes for the war.”

According to the historian Plutarch, Pericles’ defense was a masterclass in imperial logic:

The allies were paying for security, and Athens was providing it. As long as the barbarians were kept at bay and the seas were safe, Athens owed its allies nothing further. The surplus, he argued, was Athens’ to spend on public works that would bring “eternal glory” to the city.

And so, the tribute of the Delian League was funneled into the construction of the Parthenon, the Propylaea, and the other magnificent structures of the Acropolis. The greatest monuments 얼굴of Athenian democracy were, in fact, built with the money of its subjects. They stand today not only as a testament to an unparalleled artistic moment but also as enduring symbols of imperial power, funded by an empire built by subscription.

This imperial overreach, however, could not last. The resentment of the subjugated allies and the fear of rival powers, especially Sparta, led directly to the devastating Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE). The very empire that funded the Golden Age would be the cause of its downfall, a timeless lesson in how quickly the pursuit of security can transform an alliance of the free into the chains of an empire.