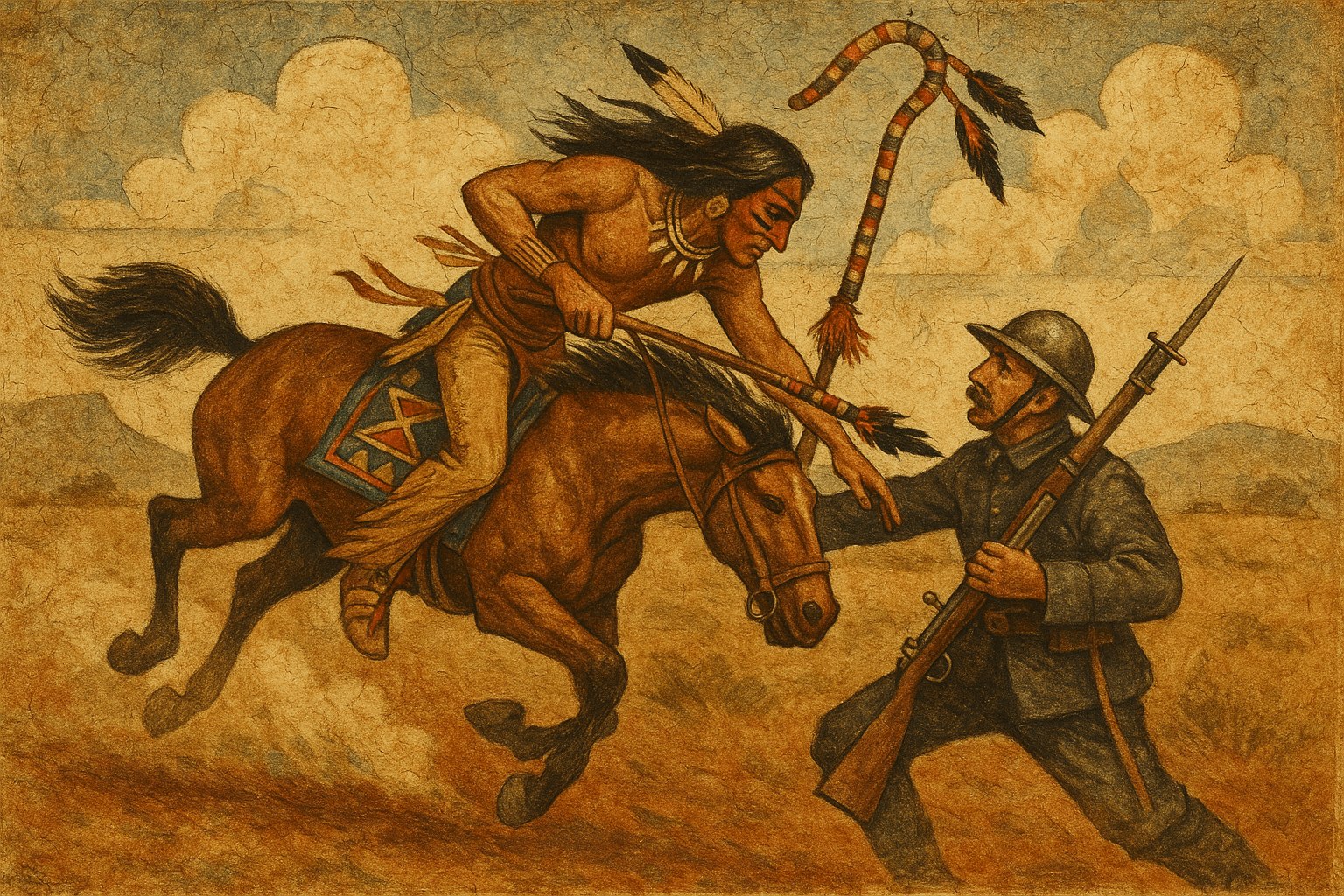

Imagine the vast, open expanse of the Great Plains in the 19th century. Two opposing groups of warriors, mounted on powerful horses and adorned in feathers and paint, charge toward one another. In our modern, cinematic imagination, this scene ends in a brutal clash of arrows, lances, and death. While that was certainly one possible outcome, another, far more profound drama was often playing out—a contest not of slaughter, but of supreme courage.

This was the world of “counting coup”, a complex and sophisticated code of honor that stood at the very heart of Plains Indian warrior culture. Far from a simple tally of kills, this system redefined bravery, elevating acts of audacious risk-taking far above the act of taking a life. It was a philosophy of warfare that is, to this day, deeply misunderstood and largely ignored in a history so often focused on conflict and conquest.

What Was “Counting Coup”?

The term “coup” comes from the French word for a “strike” or “blow”, a name given by early French fur trappers who witnessed the practice. In its essence, to count coup (pronounced ‘coo’) was to perform a specific act of bravery against an enemy. The highest and most respected coup a warrior could achieve was to touch a living, armed opponent with his hand or a special “coup stick” and escape unharmed.

This was the ultimate test of a warrior’s skill, stealth, and sheer nerve. To charge through a hail of arrows and bullets, close the distance with a dangerous foe, make physical contact, and then successfully retreat required more than just aggression. It demanded breathtaking horsemanship, impeccable timing, and a level of courage that bordered on the supernatural. Killing an enemy, especially from a distance with a bow or a rifle, was seen as a lesser achievement. After all, any man could kill from afar, but only a truly great warrior could face death, touch it on the shoulder, and ride away laughing.

A Hierarchy of Honor

Not all wartime deeds were equal. The various tribes of the Great Plains—including the Lakota, Cheyenne, Crow, and Blackfeet—had a well-defined, albeit unwritten, hierarchy of what constituted a coup. While the specific order could vary from one nation to another, the general principles were widely shared.

A typical ranking of honorable acts might look something like this:

- First Coup: Touching a living, uninjured enemy with the hand or a coup stick. This was the pinnacle of bravery.

- Second, Third, etc.: Subsequent warriors who touched the same enemy could also claim a coup, though it was of lesser distinction than the first.

- Wounding an Enemy: Drawing blood with a lance or arrow was an honored act, but still secondary to touching him.

- Killing an Enemy: While a significant act, killing an enemy often ranked below the non-lethal coups.

- Other Major Coups: Other acts of incredible daring were also recognized. Stealing a horse, particularly one tethered within an enemy’s camp, was an extremely high honor. So too was capturing an enemy’s sacred shield or weapon in hand-to-hand combat.

This system fundamentally shaped battlefield dynamics. Instead of a carefully coordinated line of soldiers advancing, Plains warfare was often a swirling, individualistic contest where warriors sought personal glory. A fallen enemy might be swarmed not just by those looking to finish him, but by warriors racing to be the first, second, or third to touch him and count coup.

Beyond the Battlefield: The Social Reward

Counting coup was not a private act. Its entire purpose was to be witnessed, verified, and celebrated publicly. Upon returning from a raid or battle, warriors would formally recount their deeds before the tribal council and the entire community. A warrior would rise and state, “I am the first who touched the enemy”, and point to a man who saw him do it. The witness would then confirm the account by saying “Ah-hay!” (“Yes!”).

Honesty was the bedrock of this system. A warrior’s word was his bond, and to be caught making a false claim was a source of unbearable shame that could ruin a man’s reputation for life. But for those whose claims were verified, the rewards were immense and tangible.

An accomplished warrior earned the right to wear specific regalia. Most famously, each coup could entitle a man to wear an eagle feather in a particular way. A red-painted hand on a warrior’s shirt might signify he had touched an enemy. Graphic symbols depicting his deeds could be painted on his tipi or his war horse. A man with many coups became a leader, his voice carrying weight in tribal councils. He was a sought-after protector, a desirable husband, and a living example for the next generation of boys. The famous eagle-feather war bonnet was not just decoration; it was a resume, a visual record of a lifetime of courage and honor.

Why Prioritize Courage Over Killing?

From a modern military perspective, this system may seem counter-intuitive. Why not simply eliminate as many enemies as possible? The answer lies in the cultural and practical realities of life on the Great Plains.

Inter-tribal warfare was typically not about annihilation or conquering territory. It was more often a cycle of raids to capture horses (a primary measure of wealth), seek revenge for a past grievance, or prove one’s manhood. In these small, nomadic societies, every warrior was a valuable hunter and protector. Widespread casualties could be devastating to a community. A system of warfare that valued displays of prowess over wholesale slaughter was, in many ways, a sustainable form of conflict resolution that allowed warriors to test their mettle without necessarily crippling their tribe.

Culturally, it reinforced the virtues most important to the Plains people: individual bravery, spiritual power, and a disdain for fear. Counting coup was the ultimate expression of control in the chaos of battle—a way to dominate an opponent spiritually and mentally, not just physically.

The End of an Era

This ancient code of honor collided violently with the expansion of the United States in the mid-to-late 19th century. The U.S. Army did not fight for honor or to count coup; it fought a campaign of total war. To soldiers armed with repeating rifles and Gatling guns, the sight of a warrior trying to touch them with a stick instead of kill them was incomprehensible, if not foolish.

As the “Indian Wars” intensified, the context for counting coup evaporated. The nature of battle changed from short, sharp raids to desperate struggles for survival against an overwhelming force. While the stories of great deeds lived on and the principles of courage remained, the practice itself was forced to fade as a new, more brutal form of warfare was thrust upon the Plains. Great leaders like Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull were renowned for the many coups they had counted in their youth, but they were forced to lead their people in a fight where survival, not honor, had become the only prize.

Counting coup remains a powerful window into a different worldview. It challenges our assumptions about warfare and violence, revealing a culture where the measure of a man was not how many lives he took, but how many times he risked his own for a fleeting moment of contact—a moment of pure, unadulterated bravery.