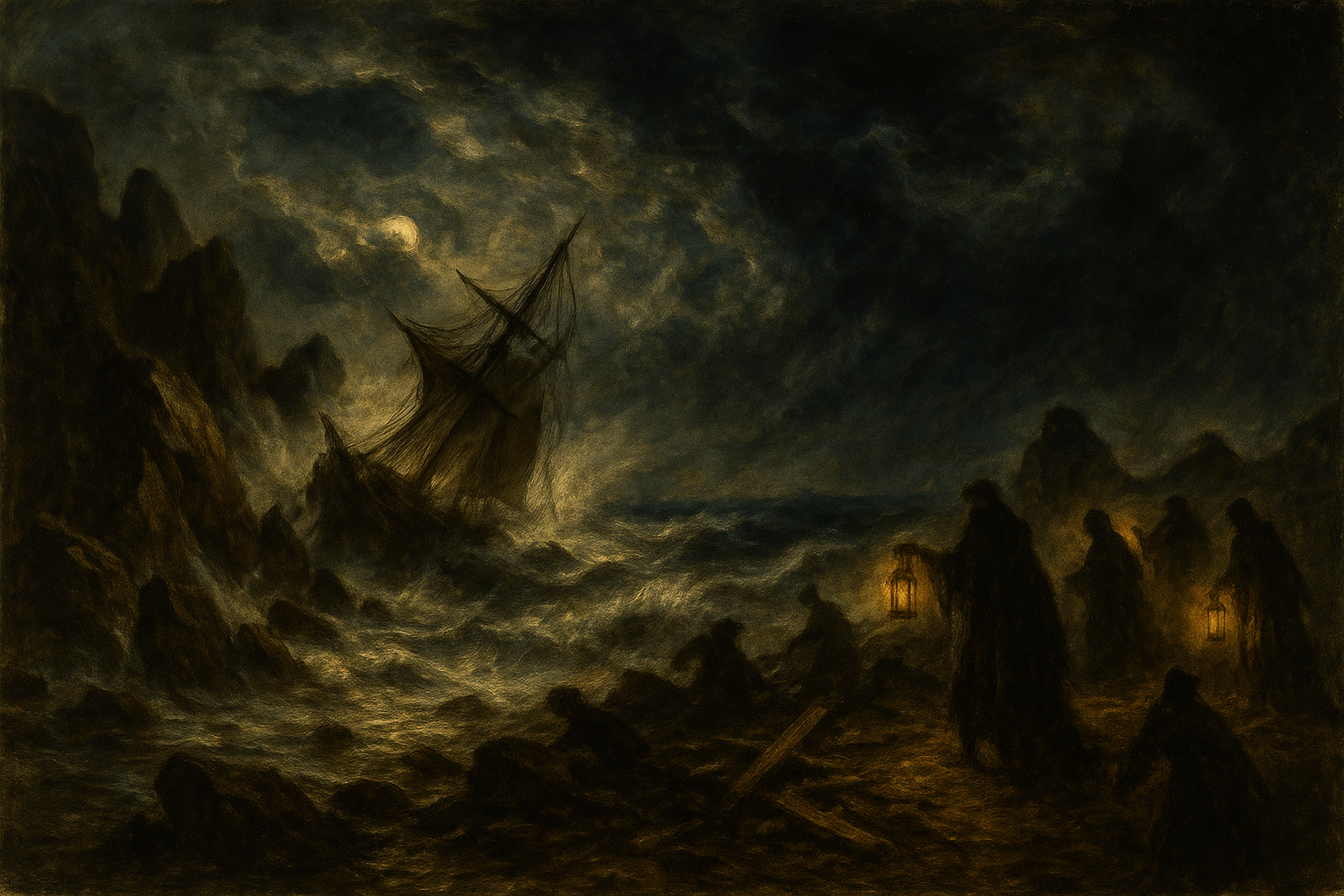

Imagine a storm-lashed Cornish night. The wind howls like a banshee, and colossal waves crash against granite cliffs. Out at sea, a merchant ship, thrown miles off course, desperately seeks a safe harbour. Then, its crew spots a light—a single, bobbing lantern on the shore, seemingly marking a calm anchorage. A wave of relief washes over them. They steer towards it, only for the ship to grind with a sickening crunch onto a hidden reef, its hull splintering. On the cliffs above, shadowy figures emerge, not to rescue, but to plunder. This is the enduring, blood-curdling legend of the Cornish Wrecker.

This image of malevolent villains luring ships to their doom is deeply embedded in popular culture, immortalised in novels like Daphne du Maurier’s Jamaica Inn. It’s a tale of greed, cunning, and murder. But as with many powerful legends, the line between folklore and fact is often blurred. To understand the story of the Cornish Wreckers, we must first separate the sinister myth from the harsh historical reality.

The Anatomy of a Myth: Luring Lanterns and Lust for Gold

The classic wrecker myth is wonderfully villainous. The stories tell of organised gangs operating along the coast. Their most infamous supposed tactic was tying a lantern to a donkey’s tail. As the donkey walked along the cliff path, the swaying light would mimic the stern light of a ship already at anchor, fooling captains into believing they had found a safe haven. Other tales speak of wreckers extinguishing lighthouses or murdering survivors to ensure there were no witnesses to their crimes and to secure the entire cargo for themselves.

These tales provided sensationalist fodder for pamphlets and newspapers in the 18th and 19th centuries, painting coastal communities as barbaric and lawless. The narratives were compelling, feeding into a broader perception of Cornwall as a remote and untamed land. But when we turn to official records—admiralty court documents, parish registers, and coroners’ reports—the evidence for this kind of deliberate, organised “wrecking-by-luring” is almost non-existent. Not a single person was ever successfully prosecuted in Cornwall for deliberately causing a shipwreck.

An Unforgiving Coast: The True Culprit

The truth is, ships didn’t need any help finding their doom on the Cornish coast. Jutting out into the Atlantic, the Cornish peninsula sits astride some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. Its coastline is a natural deathtrap of submerged rocks, jagged cliffs, and ferocious currents. The area around Land’s End and the Lizard Peninsula was so notorious it earned the grim moniker “The Graveyard of Ships.”

Before the advent of modern navigation aids, satellite technology, and reliable engines, sailing was an incredibly hazardous business. A sudden Atlantic storm, a thick sea fog, or a simple navigational error was all it took to drive a vessel onto the rocks. Historian Dr. Helen Doe has noted that between 1750 and 1850, an average of one ship wrecked on the Cornish coast every single week. The coast itself was the real wrecker; the local inhabitants were merely the witnesses and, sometimes, the beneficiaries.

From Wrecking to Salvaging: A ‘Harvest from the Sea’

So if they weren’t causing the wrecks, what were the “wreckers” actually doing? The historical act of “wrecking” was not about causing disaster, but about salvaging goods from ships that had already wrecked. For the impoverished communities of coastal Cornwall, a shipwreck was both a tragedy and an opportunity—a grim gift from the sea.

Life in these isolated fishing and mining villages was one of immense hardship. A failed harvest or a poor fishing season could mean starvation. In this context, a “wreck” was a providential event that could deliver life-saving resources. A barrel of brandy, a bolt of cloth, timber for a new roof, or salted meat could mean the difference between survival and destitution. This practice was governed by a complex mix of ancient custom and official law.

The “right of wreck” was a long-held belief that goods washed ashore were fair game for the finder. Legally, however, the situation was different. By the 18th century, a “Receiver of Wreck” was appointed to take charge of salvaged goods, which were to be held for the original owner for a year and a day. Finders were entitled to a salvage payment, but often the temptation to simply take the goods and avoid the authorities was too strong, leading to frequent clashes between locals and excise men.

The Darker Side of Salvage

This is not to say that the process of salvaging was an orderly or gentle affair. When a ship hit the rocks, it was a frantic, chaotic race against the sea. The image of an entire village—men, women, and children—scrambling over treacherous rocks to grab what they could before the tide took it away is far closer to the truth than that of a lone man with a donkey.

Violence could, and did, erupt. Fights broke out over valuable cargo, and there were sometimes brutal confrontations with customs officials or the ship’s surviving crew trying to protect their property. However, the most chilling accusation—that of murdering survivors—remains largely in the realm of folklore. While it’s impossible to rule out isolated acts of brutality in the heat of the moment, it made little economic or legal sense. Under the law, if a living person or animal escaped a wreck, the cargo remained the property of the owner, and salvors were entitled only to a fee. If there were no survivors, the entire wreck and its cargo could be claimed by the Crown or the local Lord of the Manor. Therefore, a living survivor was actually proof of a “wreck”, entitling the salvors to their claim.

Conclusion: The Man vs. The Sea

The legend of the Cornish wrecker is a powerful and enduring one, but it is a caricature that maligns generations of people who lived by the sea’s cruel whims. The reality is a far more nuanced story of poverty, desperation, and opportunism. These were not monstrous villains engineering mass murder for profit, but ordinary people grappling with a harsh environment.

They didn’t lure ships to the rocks; the rocks and the weather did that for them. Their “crime”, if it can be called that, was to claim a “harvest from the sea” that they saw as a providential right. The true villain of Cornwall’s maritime history was never the man with the lantern, but the unforgiving sea itself.