A Realm Born of Conflict

The khanate’s story begins with its namesake, Chagatai Khan, the second son of Genghis Khan. Known as a stern and uncompromising traditionalist, Chagatai was the great enforcer of the Yassa, the secret Mongol code of law. Upon his father’s death, he was granted a vast territory covering modern-day Central Asia, including the wealthy, ancient cities of Transoxiana like Samarkand and Bukhara.

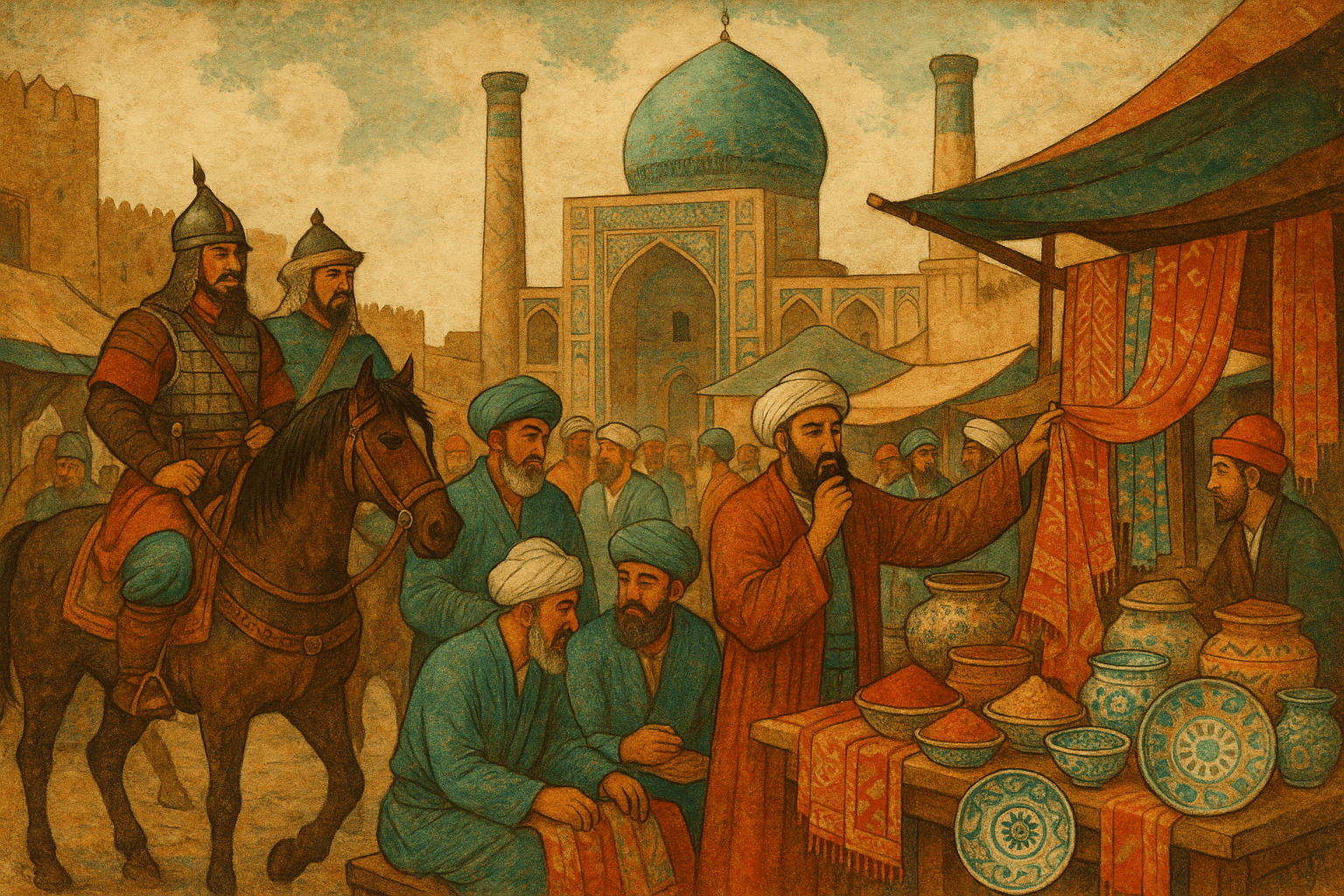

This inheritance immediately created a fundamental tension. The ruling elite was a nomadic Mongol minority, deeply attached to their steppe traditions and shamanistic beliefs. Their subjects, however, were a settled, sophisticated majority of Turkic and Persian peoples who had been part of the Islamic world for centuries. Chagatai’s rigorous adherence to the Yassa, which included prohibitions against practices like ritual slaughter of animals and ablutions in running water, put him in direct conflict with Islamic customs. For its first few decades, the khanate was a state where Mongol tradition actively suppressed, or at least discouraged, full cultural assimilation.

The Great Divide: From Steppe Nomads to Islamic Sultans

The inherent conflict between the nomadic Mongol way of life and the settled Perso-Islamic culture of Transoxiana couldn’t last forever. By the early 14th century, the khanate was tearing itself in two, not just politically, but culturally.

A pivotal figure in this transformation was Kebek Khan (r. 1318-1326). Breaking with tradition, Kebek moved his court away from the eastern steppes and established a fixed capital near the city of Qarshi in the agricultural heartland. He promoted settled life, reformed the administration along Persian models, and standardized the currency, issuing silver coins bearing his name. While not a Muslim himself, his policies favored the sedentary population and created an environment where Islamic culture could flourish within the state apparatus.

The decisive break came with Tarmashirin Khan (r. 1331-1334). After a successful campaign in India, he converted to Islam, took the title Sultan, and declared it the state religion. This was a monumental step, but it proved to be one step too far for the traditionalists. The Mongol princes of the eastern steppes—a region known as Moghulistan—rose in revolt, accusing Tarmashirin of abandoning the sacred laws of Genghis Khan. They overthrew and killed him, leading to the permanent schism of the khanate. From this point on, Central Asia was divided:

- The Western Chagatai Khanate (Transoxiana), which became increasingly Turkified, Islamized, and urbanized.

- Moghulistan in the east, where the rulers desperately tried to preserve their nomadic Mongol heritage.

The Crossroads of Culture: Language, Religion, and Trade

It was in the western, Islamic half of the khanate that the most enduring legacy was forged. In this multicultural melting pot, a remarkable synthesis took place. Perhaps the most significant product of this fusion was the development of the Chagatai language.

This was not the Mongol language of the conquerors but a sophisticated literary Turkic tongue. Built on the local Karluk Turkic dialect, it was heavily enriched with vocabulary and stylistic elements from Persian and Arabic. Chagatai became the lingua franca of administration, poetry, and literature across Central Asia. Its elegance and prestige were such that it remained the dominant literary language for Turkic peoples for over 400 years. Its influence is evident in the works of giants like the 15th-century poet Ali-Shir Nava’i and even Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire in India, who wrote his famous autobiography, the Baburnama, in Chagatai.

Simultaneously, the Islamization process deepened. It wasn’t just a matter of the rulers converting; Sufi mystics, particularly from the influential Naqshbandi order, traveled through the region, converting Turco-Mongol tribes and embedding a deeply spiritual form of Islam into the fabric of society. While Mongol military and tribal structures remained, the cultural and religious identity of the region’s elite became irrevocably Islamic.

The Heirs of Chagatai: Timur and the Timurid Renaissance

By the mid-14th century, the Western Chagatai Khanate had devolved into a collection of feuding tribal confederations. It was from this chaos that its most famous successor emerged: a minor noble from the Turkified Barlas Mongol tribe named Timur, known to the West as Tamerlane.

Timur was a product of the Chagatai world. While he was a ruthless conqueror who built an empire stretching from India to Turkey, he was also a master synthesizer. He claimed the legacy of Genghis Khan, yet he ruled as a devout Muslim emir. He was not a direct Genghisid descendant, so he cleverly legitimized his rule by installing puppet khans from the Chagatai line while holding the real power himself. His state, the Timurid Empire, was the ultimate expression of the Chagatai legacy: a Turco-Mongol military machine governing a Perso-Islamic state.

Under Timur and his successors, this synthesis produced the glorious Timurid Renaissance. They poured the wealth of their conquests into their capital, Samarkand, transforming it into the jewel of the Islamic world. The breathtaking blue-tiled mosques, madrassas, and observatories—like the Registan square and Ulugh Beg’s observatory—are the direct architectural heirs of the cultural fusion that began under the Chagatais.

A Legacy Forged in Fusion

The Chagatai Khanate may lack the fame of its sister states, but its historical importance is immense. It was the crucial arena where Mongol identity did not simply conquer, but transformed. Its legacy is not one of imperial ruin, but of cultural creation. It gave Central Asia:

- A new literary language that would define Turkic culture for centuries.

- A Turco-Islamic ruling identity that blended steppe heritage with urban faith.

- The political and cultural foundation for the spectacular Timurid Empire and, by extension, the Mughals of India.

In the end, the Chagatai Khanate is remembered not for being a purely Mongol state that faded away, but for successfully overseeing the birth of a new, dynamic Turco-Islamic civilization that would dominate the heart of Asia long after the last echoes of Genghis Khan’s armies had disappeared.