This was no simple act of madness. The ghoulish spectacle was the terrifying culmination of a bitter political power struggle that had engulfed Rome in the wake of the Carolingian Empire’s collapse. To understand how a dead man ended up on trial, we must look at the treacherous world he left behind.

The Players on a Deadly Stage

The story of the Cadaver Synod revolves around two key figures, whose careers were defined by the political factions vying for control of the Italian peninsula.

The Accused: Pope Formosus

Before becoming pope, Formosus was a highly respected cardinal and missionary who had great success in Bulgaria. However, he was also a political player. His ambition and involvement in secular politics led to his excommunication by Pope John VIII, forcing him to flee Rome. He was later reinstated, and in 891 AD, he was elected pope—an outcome that deeply angered a powerful local dynasty.

The main source of conflict was the title of Holy Roman Emperor. The powerful Dukes of Spoleto, an Italian noble family, believed the title was theirs to control. They pressured Formosus to crown Guy III of Spoleto, which he did. But Formosus feared the Spoletans’ growing power and secretly sought an outside force to counterbalance them. He invited Arnulf of Carinthia, the King of East Francia, to invade Italy and claim the imperial crown. In 896 AD, Formosus crowned Arnulf Holy Roman Emperor, a direct betrayal of the Spoletan family. This act sealed his posthumous fate.

The Prosecutor: Pope Stephen VI

After Formosus died in 896 AD, his immediate successor lasted only fifteen days. Then came Stephen VI, a man firmly in the pocket of the Spoletans. He had been made a bishop by Formosus, but his true allegiance lay with the vengeful Empress Ageltrude, Guy III’s widow, and her son Lambert. Encouraged (and likely commanded) by his Spoletan patrons, Stephen VI sought not just to erase Formosus’s legacy, but to ritually annihilate it.

A Papacy Up for Grabs: The Chaos of Post-Carolingian Rome

The late 9th century was a period of immense instability. Charlemagne’s once-mighty empire had fractured, leaving a power vacuum in Italy. Without a strong emperor to protect it, the papacy became a prize for warring aristocratic families. Control of the papacy meant the power to legitimize rule, crown emperors, and control vast territories and wealth. Rome descended into a cesspool of conspiracy, bribery, and violence, an era later historians would call the Saeculum Obscurum, or the “Dark Century.”

The crowning of Arnulf by Formosus was the ultimate offense to the Spoletan faction. When Arnulf suffered a stroke and was forced to withdraw from Italy, the Spoletans re-entered Rome, hungry for revenge. The Cadaver Synod was their tool for vengeance.

The Ghoulish Spectacle: The Trial of 897 AD

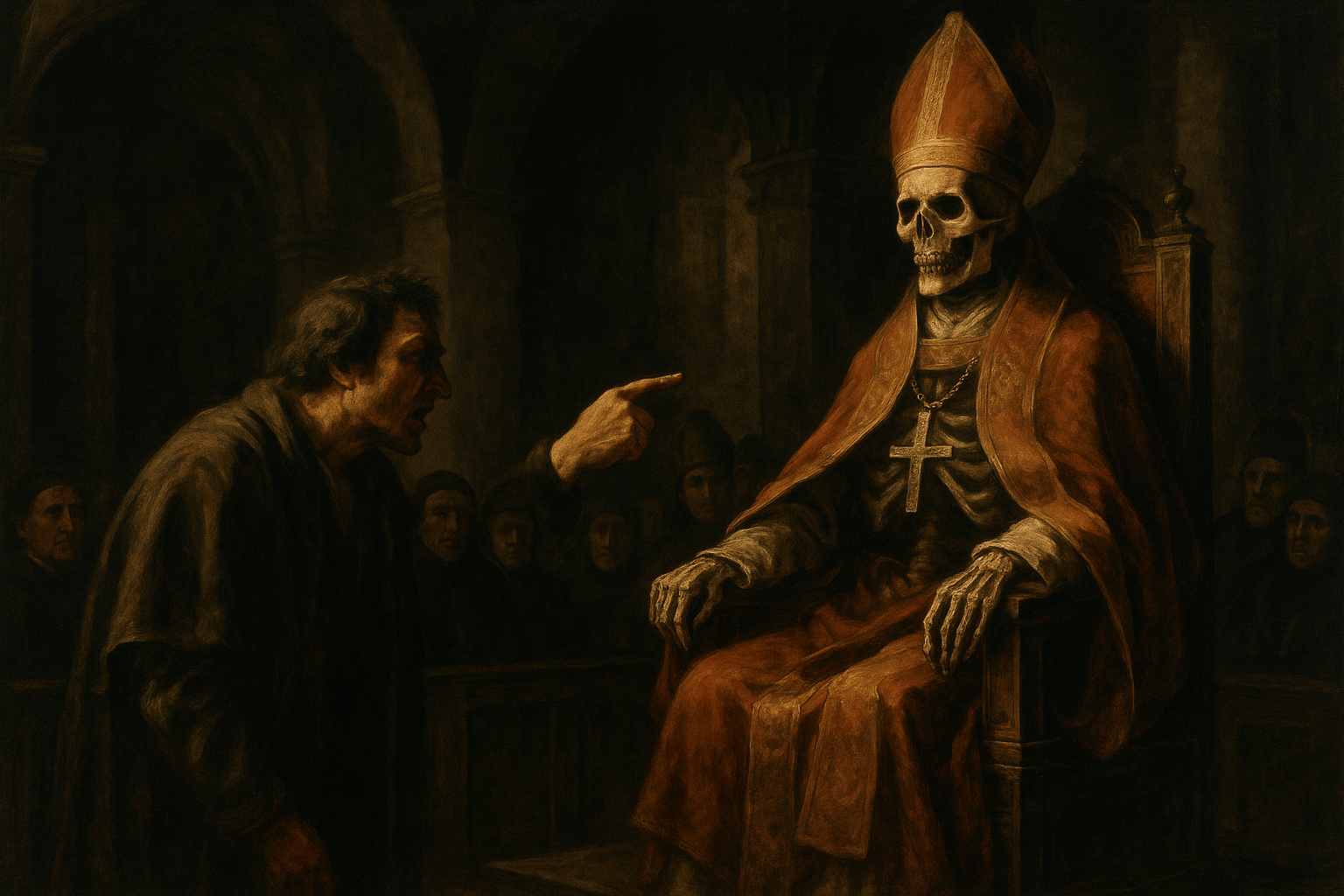

Under Stephen VI’s orders, the tomb of Pope Formosus was opened. His rotting body was exhumed, clothed in the sacred papal robes, and placed upon a throne in the basilica. The synod began.

Pope Stephen VI presided, screaming accusations at the silent, decaying figure. A young deacon, trembling with fear, was forced to stand beside the corpse and “answer” on its behalf. The charges against Formosus were threefold:

- Perjury: For allegedly breaking an oath never to return to Rome.

- Ambition: For having transgressed canon law by accepting the papacy when he was already a bishop of another city (Porto). This was known as “transmigration” of sees and was technically forbidden.

- Violating Canons: For having carried out the functions of a bishop while he had been deposed.

The verdict was a foregone conclusion. The corpse was found guilty. The judgment was swift and brutal. Formosus’s papacy was declared null and void. All his acts, measures, and ordinations were retroactively annulled. This created immediate chaos, as it meant that countless priests and bishops across Europe—including Stephen VI himself—had suddenly been rendered illegitimate.

The desecration then began. Guards stripped the decomposing body of its papal vestments. Then, with a chilling formality, Stephen VI ordered that the three fingers of Formosus’s right hand—the fingers used to give blessings—be hacked off. The mutilated corpse, now clad in layman’s clothes, was dragged through the streets of Rome and, as a final indignity, thrown into the Tiber River.

The Reckoning: An Act Too Far

Pope Stephen VI and his Spoletan allies had grievously miscalculated. Far from cementing their power, the Cadaver Synod horrified the Roman populace. The sacrilege was seen as an offense not just against a man, but against God and the sanctity of the papal office. Shortly after the trial, an earthquake struck Rome, damaging the Basilica of St. John Lateran itself. This was widely interpreted as a sign of divine outrage.

The public mood, already simmering with discontent, boiled over. The annulment of Formosus’s ordinations had thrown the Church’s hierarchy into disarray and threatened the spiritual standing of thousands. An insurrection broke out. The pro-Formosus faction rallied, and Stephen VI was overthrown, stripped of his papal insignia, and cast into prison. In July or August of 897, just a few months after his ghoulish trial, he was strangled to death in his cell.

The Lingering Stench of Scandal

The Cadaver Synod stands as one of the darkest moments in the history of the Catholic Church. The story didn’t end with Stephen’s death. Subsequent popes would spend years reversing, then reinstating, then reversing again the verdict against Formosus. His body was eventually recovered from the Tiber by monks and given a proper burial, but the political turmoil continued.

The event serves as a stark and visceral reminder of what happens when spiritual authority becomes hopelessly entangled with raw, secular power. It wasn’t about heresy; it was about politics. The trial of Pope Formosus, the corpse in the dock, reveals a time when the See of Peter was just another bloody prize in a game of thrones played by ruthless nobles and ambitious churchmen.