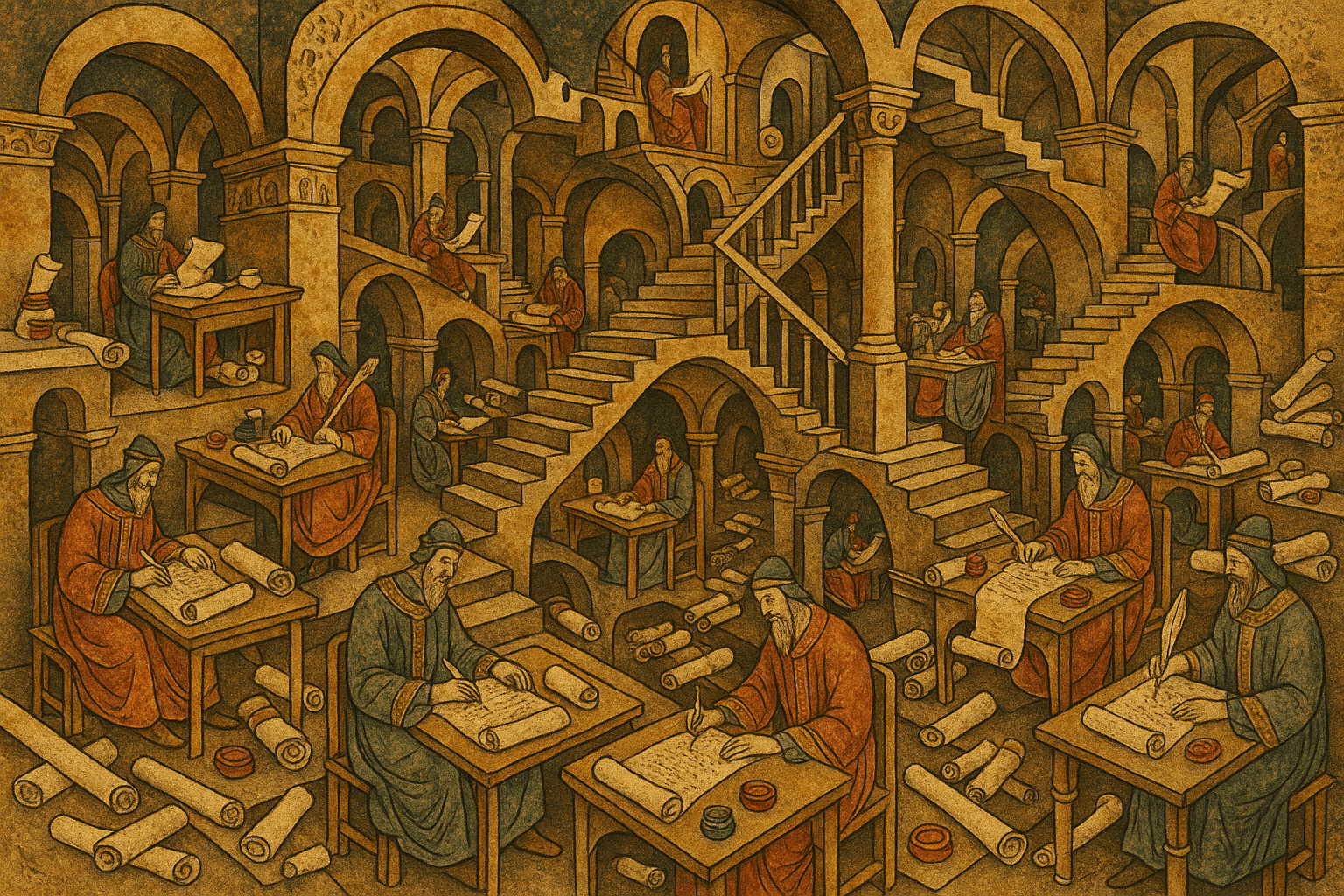

This vast, complex, and often bewildering administrative machine was the empire’s true bedrock. It collected the taxes that paid the soldiers, maintained the roads that carried the armies, and enforced the laws that provided stability. While emperors came and went, the bureaucracy was the perpetual engine of the state, a key reason why Byzantium outlasted its western counterpart by a thousand years.

An Evolved Roman Legacy

The Byzantine bureaucracy wasn’t invented overnight. It was a direct descendant of the late Roman administrative system, reformed and expanded by emperors like Diocletian and Constantine the Great in the 3rd and 4th centuries. A core principle they established was the strict separation of civil and military authority. The goal was to prevent powerful generals from using their provincial armies to march on the capital and claim the throne—a chronic problem that had plagued Rome.

The system was hierarchical and geographically extensive. At the top was the central government in Constantinople, a vast network of ministries and offices clustered around the Great Palace. Below this, the empire was divided into provinces (later called themes), each with its own administrative staff that reported back to the capital. This structure allowed a single emperor, believed to be God’s regent on Earth, to project his authority from the Danube frontier to the deserts of Egypt.

The Menagerie of Titles: A Guide to the Imperial Labyrinth

To a modern observer, the Byzantine system of titles is a dizzying, almost comical, alphabet soup of Greek and Latin. These weren’t just job descriptions; they were coveted ranks in a finely stratified society, denoting one’s proximity to the emperor and, therefore, to power. An official’s full title could be a long chain of honorifics, each carrying a specific weight and salary.

The central administration was run by a group of powerful ministers. Here are just a few of the key players you might encounter in the corridors of the Great Palace:

- Magister Officiorum (Master of Offices): Initially the head of the palace secretariat and court ceremonies, this official became one of the most powerful men in the empire. He controlled the imperial guard, the arsenals, the fearsome public intelligence service (the agentes in rebus), and the imperial postal system. He was, in essence, a combination of chief of staff, interior minister, and intelligence director.

- Quaestor Sacri Palatii (Quaestor of the Sacred Palace): The emperor’s chief legal advisor and spokesman. The Quaestor was responsible for drafting laws and responding to petitions, functioning as the supreme judicial officer of the empire.

- Logothetes tou Dromou (Logothete of the Course): Originally the master of the public post (the dromos), this office evolved into the empire’s chief minister for foreign affairs. He managed diplomacy, received foreign ambassadors, and handled the vast network of spies and informants operating abroad.

- Sakellarios: The general financial comptroller, or chief treasurer. The Sakellarios was not in charge of a single treasury but oversaw all the state’s financial departments, making him the ultimate watchdog of the imperial purse.

A unique feature of the Byzantine court was the prominent role of eunuchs. Unable to sire children and found their own dynasties, they were considered inherently more loyal to the reigning emperor. They could rise to the highest offices, holding titles like Praepositus Sacri Cubiculi (Grand Chamberlain), which gave them unparalleled access to the emperor and immense influence over policy.

The Engine of the State: Taxes, Laws, and Information

All these grand titles would have been meaningless without a system that could effectively govern. The bureaucracy excelled at three core functions: taxation, law, and communication.

The Relentless Pursuit of Revenue

The Byzantine state’s primary function was to collect taxes, and it did so with remarkable efficiency. The system rested on a foundation of detailed land registers known as cadastres. Scribes would meticulously record the ownership, size, and quality of every plot of land in a province. This data was used to assess the two main taxes: the annona (a tax on land, usually paid in kind) and the capitatio (a poll tax on individuals).

This regular, predictable flow of revenue was the empire’s lifeblood. It funded a professional, salaried army and navy, lavish diplomacy designed to awe barbarian chieftains, and monumental construction projects like the Hagia Sophia. While burdensome for the peasantry, this tax system provided a level of fiscal stability unimaginable in the fragmented kingdoms of Western Europe.

A World of Law and Precedent

The bureaucracy was also the guardian and administrator of Roman law. The monumental codification of law under Justinian I, the Corpus Juris Civilis, was the product of this legal-bureaucratic tradition. For centuries afterward, state officials and judges applied these complex laws, providing a consistent and predictable legal framework across the empire. Citizens could, in theory, petition the state and expect a ruling based on established precedent, a concept that fostered social order.

The Dromos: The Imperial Nervous System

Overseen by the Logothetes tou Dromou, the public post was far more than a mail service. It was the empire’s nervous system—a network of roads, waystations, and mounted couriers that enabled the swift transmission of decrees, intelligence reports, and official travel. This system allowed the emperor in Constantinople to receive news from a distant frontier in a matter of weeks, not months, giving the centralized state a crucial advantage in responding to crises.

The Double-Edged Sword: Corruption and Rigidity

For all its strengths, the Byzantine bureaucracy was far from perfect. Its complexity and opacity made it a breeding ground for corruption. The sale of offices (suffragia) was a common practice, allowing wealthy individuals to buy their way into positions where they could enrich themselves through bribes and extortion. The endless paperwork and official channels could also lead to crippling inertia. The state’s obsession with order and precedent (known as taxis) could make it slow to adapt to new and unforeseen challenges.

Yet, despite these flaws, the system endured. For a thousand years, the Byzantine bureaucratic machine ground on, collecting revenue, administering justice, and preserving the traditions of Rome. It was the rigid skeleton that supported the empire through countless invasions, civil wars, and plagues. While emperors and generals won the battles, it was this army of faceless, pen-pushing bureaucrats who truly won the war of survival.