In our hyper-connected world, our days are dictated by the quiet buzzes and gentle chimes of our smartphones. Calendars schedule our meetings, timers manage our tasks, and a thousand apps promise to optimize our productivity and mindfulness. We have a digital exoskeleton that structures our time. But what did people do centuries before the first line of code was ever written? For the monks, priests, and devout laity of the Middle Ages, the answer was a book: the Breviary.

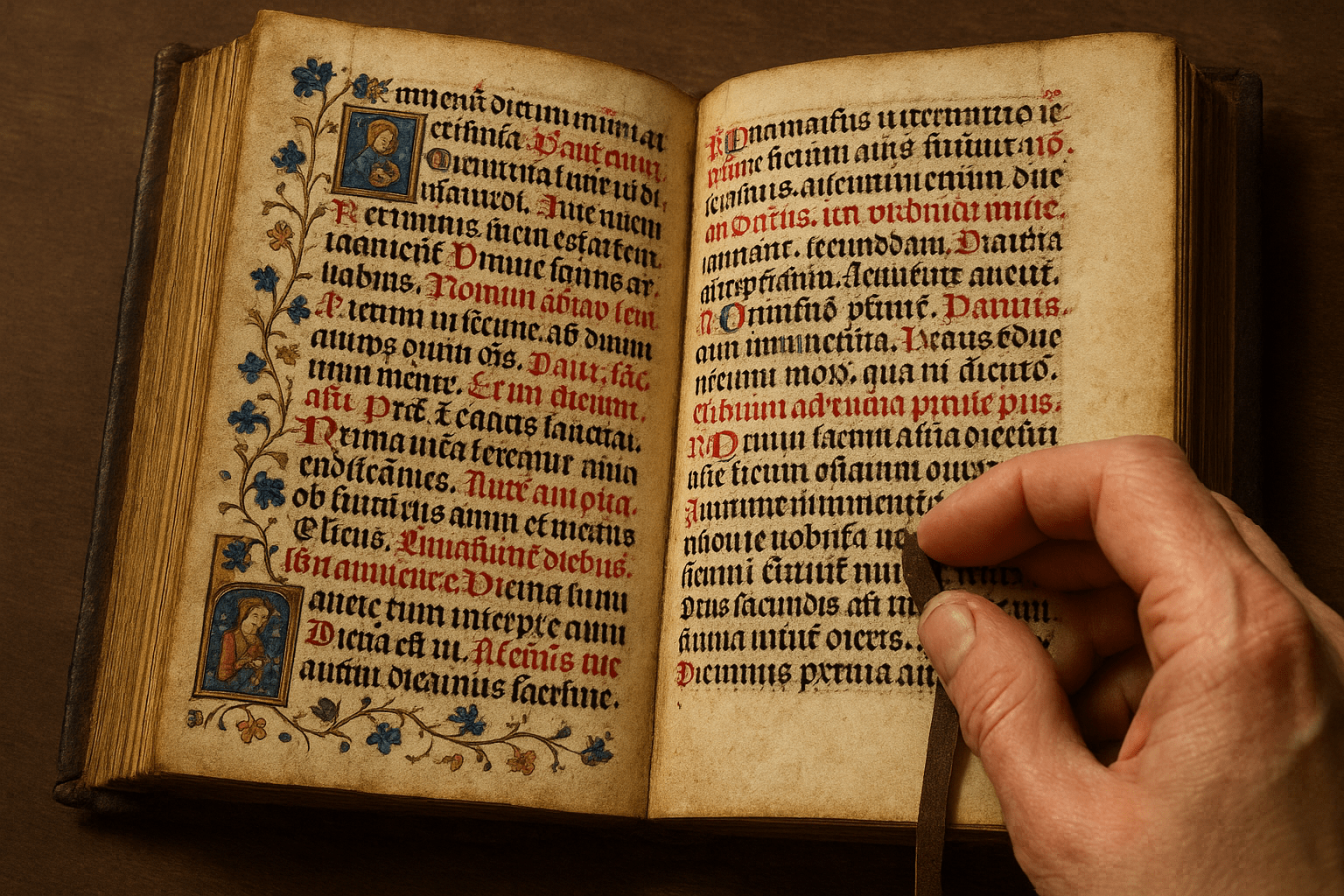

Far from being just a simple prayer book, the Breviary was the medieval equivalent of a powerful, all-in-one productivity and spiritual wellness app. It was a masterpiece of information design, a complex, cross-referenced database bound in leather and parchment that organized the user’s entire life around a single, central purpose: the sanctification of time through prayer.

The ‘Operating System’: The Divine Office

To understand the Breviary, you first have to understand its “software”—the Divine Office, also known as the Liturgy of the Hours. This was the Church’s official, daily cycle of public prayer. Its goal was to consecrate the entire day and night to God, fulfilling the biblical injunction to “pray without ceasing.”

Rooted in Jewish tradition and formalized by early Christian monastic communities, particularly under the 6th-century Rule of St. Benedict, the Divine Office divided the 24-hour day into eight distinct prayer times, or “hours.” These were the sacred appointments that a monk’s life revolved around, the non-negotiable “notifications” that called him from work, study, or sleep.

- Matins: The long, nocturnal vigil, recited during the night.

- Lauds: A prayer of praise at dawn, as the sun rose.

- Prime: The “first-hour” prayer of the morning.

- Terce: The “third-hour” prayer, around 9 a.m.

- Sext: The “sixth-hour” prayer at midday.

- None: The “ninth-hour” prayer, around 3 p.m.

- Vespers: The major evening prayer service as the sun set.

- Compline: The final “completion” prayer before retiring for the night.

Praying this cycle was not just a private devotion; it was a liturgical act, the public work of the Church. The Breviary was the tool that made this complex “operating system” of prayer possible for individuals and small groups, especially those outside the fixed schedule of a large monastery choir.

A Database in a Book: The Breviary’s Information Architecture

Calling the Breviary a “book” is a bit like calling the internet a “pamphlet.” It was, in reality, a brilliant compilation of many different books, all artfully arranged into a single, portable volume. This was a crucial innovation. Before the 13th century, a monastery choir would need a whole shelf of books to perform the Office: a Psalter for the psalms, an Antiphonary for the antiphons, a Hymnal for hymns, a Lectionary for scripture readings, and so on.

The Breviary ingeniously consolidated all of this data. Its genius lay in its complex, non-linear structure. A user couldn’t simply read it from front to back. To pray for a specific day and hour, one had to navigate multiple sections, much like querying a database. The main “data tables” included:

- The Psalter: The heart of the Breviary, containing all 150 Psalms, typically arranged to be prayed over the course of one week.

- The Temporale (Proper of Time): This section contained the variable prayers, readings, and antiphons for the specific seasons of the liturgical year, following the life of Christ (e.g., Advent, Christmas, Lent, Easter). This was the “seasonal theme” of the app.

- The Sanctorale (Proper of Saints): A liturgical calendar of saints’ feast days, with specific readings and prayers for each major saint. This was the “daily event” feed.

- The Common of Saints: A set of generic prayers for saints who didn’t have a specific feast prescribed. It provided templates for categories like “Common of Martyrs”, “Common of Virgins”, or “Common of Pastors.”

- Various other sections: These could include the Office for the Dead, specific canticles, and a collection of hymns.

‘Using the App’: The Medieval User Experience

So, how did a 14th-century priest actually use this device? He didn’t have a search bar. He had the Ordo or Kalendar at the front of the book. This calendar was the “home screen”, telling him exactly what day it was in the Church’s year.

Let’s imagine it’s December 4th, and the Ordo indicates it’s a feria (a weekday) in the First Week of Advent, but it’s also the feast day of St. Barbara. The user would have to perform a mental “query”:

- Go to the Psalter for the psalms appointed for a Tuesday.

- Go to the Temporale for the specific Advent antiphons, short reading, and closing prayer.

- Flip to the Sanctorale to see what prayers were prescribed for St. Barbara.

- Follow the instructions—printed in red ink, hence the name rubrics (from the Latin ruber, “red”)—to see whether St. Barbara’s feast “outranked” the Advent weekday. The rubrics might instruct him to use the Advent prayers but add a “commemoration” of St. Barbara, which involved yet another set of prayers.

This process was repeated for all eight hours of the day. To keep their place, users relied on a sophisticated system of colored ribbons and leather tabs. Wealthier patrons might have a Breviary with lavish illuminations and gold leaf, a high-tech device that was also a priceless work of art.

The Evolution and Legacy of a Spiritual Technology

The Breviary’s development was driven by a need for portability. It was particularly championed by the Franciscan friars of the 13th century. As itinerant preachers on the move, they couldn’t be tied to a monastery’s large library of choir books. They needed a single, compact volume that contained everything. This Franciscan “mobile edition” was so effective that it was eventually adopted in Rome and spread throughout the Western Church.

For centuries, the Breviary remained a cornerstone of clerical life. The Council of Trent in the 16th century issued a standardized version, the Breviarium Romanum, which remained largely unchanged for 400 years. It was only after the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s that the Divine Office was significantly revised, simplified, and given a new name: the Liturgy of the Hours.

Today, the Breviary’s long history has come full circle. The Liturgy of the Hours, its direct descendant, is now widely available as an actual app for smartphones and tablets. With a single tap, a user can access the correct prayers for the day, perfectly arranged, with no need for ribbons or flipping through sections. The “rubrics” are now automated. Yet, the fundamental purpose remains the same as it was for a medieval monk consulting his parchment: to weave prayer into the very rhythm of daily life.

The Breviary stands as a testament to the timeless human desire to find order and meaning. It was a technology of faith, an information system for the soul, and a powerful tool that, without a single circuit or screen, shaped the time, minds, and spirits of a civilization for over a thousand years.