In the final decades of the 19th century, a tidal wave of European imperialism was washing over the African continent. At the 1884 Berlin Conference, a group of European powers, without a single African representative present, drew lines on a map, carving up lands and peoples in what became known as the “Scramble for Africa.” The prevailing belief in London, Paris, and Rome was one of manifest destiny—that European military technology and racial superiority made conquest inevitable. But in the highlands of Ethiopia, an ancient empire was about to deliver a stunning rebuttal to this narrative, one that would echo across the globe for generations.

The Seeds of Conflict: A Treaty Lost in Translation

The road to war began not with a gunshot, but with a penstroke and a deliberate deception. In 1889, Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia signed the Treaty of Wuchale with Italy. Menelik, a shrewd modernizer, was keen to secure his empire’s borders and gain access to European firearms. The treaty was meant to foster friendly relations and define the borders between Ethiopia and the Italian colony of Eritrea.

However, the treaty contained a fatal flaw: the Amharic and Italian versions of a key article said two very different things. Article 17 of the Amharic version stated that the Emperor of Ethiopia could use the good offices of the Italian government to conduct his foreign affairs. It was an option. The Italian version, however, stated that he must conduct all foreign affairs through Italy. This single word, “could” versus “must,” effectively turned Ethiopia into an Italian protectorate on paper.

When Menelik learned of this treachery, he was furious. After years of diplomatic attempts to have the article corrected failed, he made a bold move. In 1893, he renounced the entire Treaty of Wuchale, writing to the European powers: “Ethiopia has need of no one; she stretches out her hands unto God.” The message was clear: Ethiopian sovereignty was not for sale, and he would defend it by force if necessary.

A Nation United: Menelik’s Call to Arms

Anticipating the inevitable conflict, Emperor Menelik II and his influential wife, Empress Taytu Betul, began one of the most remarkable mobilization efforts in modern history. Menelik was not just an emperor; he was a unifier. He had spent years consolidating his power, bringing regional lords (known as Ras), who were often rivals, under a single banner. When the Italian threat became undeniable, he issued a proclamation that stirred the heart of the nation:

“Enemies have now come upon us to ruin our country and to change our religion… With the help of God, I will not deliver up my country to them. Today, you who are strong, give me your strength; and you who are weak, help me by prayer.”

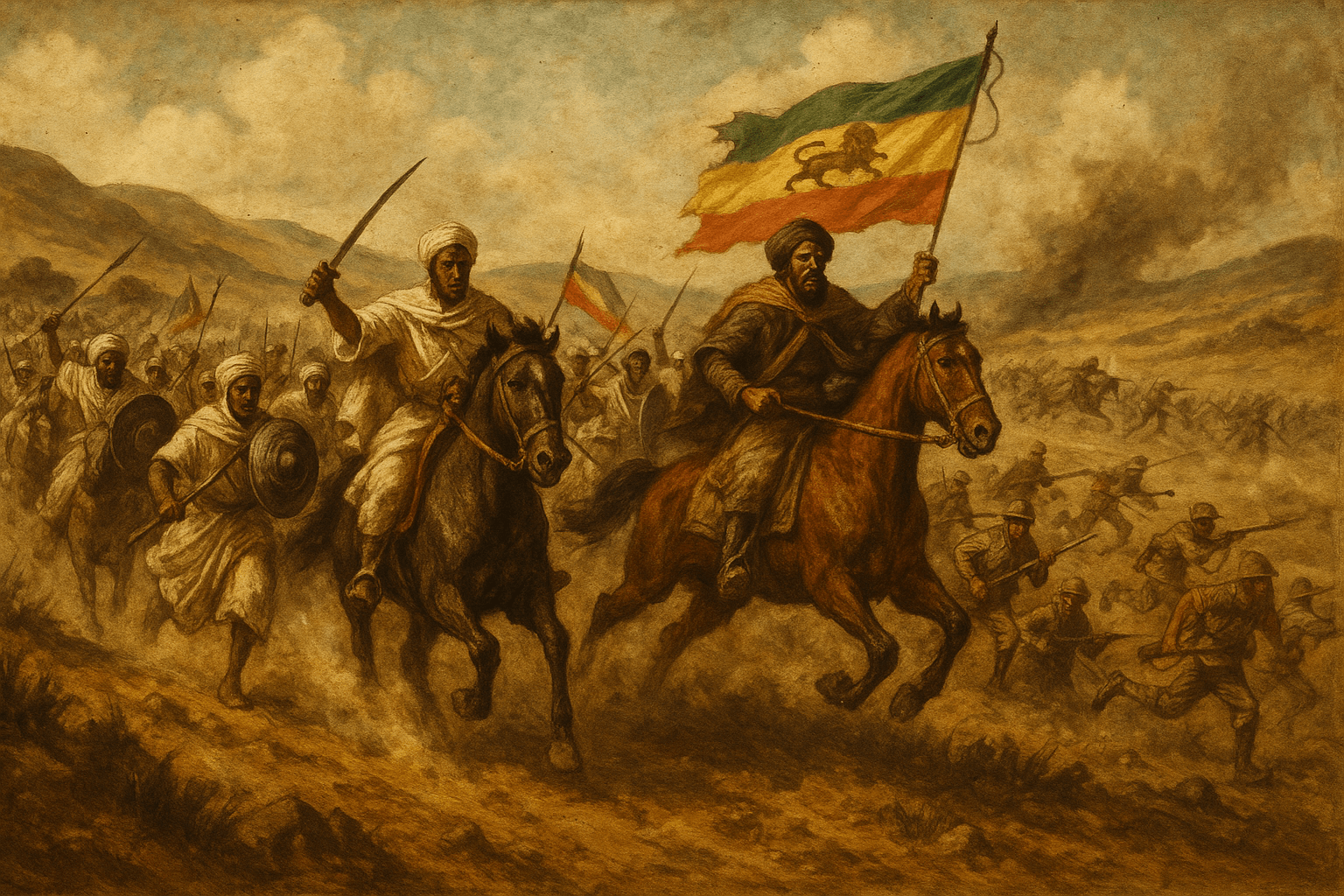

The response was overwhelming. From every corner of the vast, mountainous empire, armies marched toward the capital, Addis Ababa, before moving north to face the Italians. Vassals who had once fought against Menelik now marched alongside him. Leaders like Ras Makonnen (father of the future Emperor Haile Selassie), Ras Alula Engida (a famed military strategist), and Ras Mangesha Yohannes put aside old feuds for the sake of the nation. This created a unified Ethiopian force estimated at around 100,000 soldiers, a staggering number that the Italians grossly underestimated.

This army was not a simple, poorly-equipped militia. Thanks to Menelik’s foresight, it was armed with tens of thousands of modern rifles and supplemented by a traditional force of cavalry and swordsmen. Furthermore, a complex and efficient supply network, organized largely by Empress Taytu, ensured the massive army could be fed and maintained in the field—a logistical feat the Italians could not match.

The Road to Adwa: Italian Arrogance and Miscalculation

On the other side, the Italian commander, General Oreste Baratieri, was a man blinded by arrogance and immense political pressure from Rome. He commanded a smaller, but technologically advanced, force of around 17,700 men, composed of Italian regulars and Eritrean auxiliaries (askaris). Baratieri disdained the Ethiopian army, viewing it as an undisciplined horde that would crumble in the face of European firepower.

His campaign was plagued by problems from the start. His supply lines were stretched thin across hostile territory, his maps were woefully inaccurate, and his intelligence on the size and location of Menelik’s army was dangerously flawed. As his army’s supplies dwindled, Baratieri found himself in a difficult position. On February 29, 1896, goaded by a telegram from the Italian Prime Minister questioning his courage, he made a fateful decision: he would advance his forces under the cover of darkness for a surprise dawn attack on the Ethiopian camp near the town of Adwa.

March 1, 1896: A Dawn of Defeat for Italy

Baratieri’s plan was a disaster in the making. He divided his army into three columns, ordering them to execute a complex maneuver at night through a labyrinth of mountains and valleys they did not know. The columns quickly became lost, disoriented, and separated from one another.

But the Ethiopians were not asleep. Menelik’s and Ras Alula’s scouts had been watching the Italians for days. As the Italian columns blundered through the darkness, their movements were reported to the Emperor. When dawn broke on March 1, 1896, the Ethiopians were not surprised; they were prepared.

Menelik and his generals seized the opportunity. Instead of facing a unified Italian line, they could attack each of the isolated columns individually. With an imperial cry of “Reap them!”, the Ethiopian warriors, with Emperor Menelik, Empress Taytu, and the Ras leading their own contingents, descended upon the Italians.

The battle was a scene of chaos and heroism. Ethiopian soldiers, chanting and charging, swarmed the Italian positions. They neutralized the artillery advantage by engaging in fierce, close-quarters combat where their superior numbers and knowledge of the terrain were decisive. One Italian column was annihilated, another surrounded and forced to surrender, and the third was routed in a desperate retreat. By midday, the battle was over. The modern European army had been utterly shattered.

The Italian losses were catastrophic: nearly 7,000 killed, 1,500 wounded, and over 3,000 captured. The Ethiopians had secured one of the most decisive victories in the history of anti-colonial resistance.

The Aftermath: A Legacy of Sovereignty and Inspiration

The news of the defeat at Adwa sent shockwaves through Europe. The government in Italy collapsed. In the subsequent Treaty of Addis Ababa, Italy was forced to recognize the absolute sovereignty of Ethiopia, making it the only African nation, alongside Liberia, to successfully resist European colonization during the Scramble for Africa.

But the legacy of Adwa extends far beyond the borders of Ethiopia. It was a profound psychological victory that shattered the carefully constructed myth of European invincibility. It proved that an African nation, through strategic leadership, national unity, and sheer determination, could defeat a modern colonial power. For budding nationalist movements across Africa and for people of African descent in the diaspora, Adwa became a powerful symbol of black pride, resistance, and the dream of self-determination. It was a beacon of hope, a testament to the fact that the future of Africa would not be decided exclusively in the halls of power in Europe.