Imagine reading a historical document that lists a king who ruled for 28,800 years. His successor reigned for 36,000 years. This isn’t a page from a fantasy novel, but an artifact from the dawn of civilization: the Sumerian King List. This extraordinary text, inscribed on cuneiform tablets over 4,000 years ago, presents a lineage of rulers that stretches from a mythical, god-like past into a more recognizable historical era. At its heart is a dramatic cataclysm—a Great Flood—that separates an age of impossibly long-lived kings from the mortal rulers who came after. This document is more than a simple list; it’s a profound statement about how the ancient Sumerians viewed kingship, time, and their place in the cosmos.

What is the Sumerian King List?

The Sumerian King List (or SKL) is an ancient text written in the Sumerian language that records the rulers of Sumer and neighboring regions. Several versions exist, most famously the Weld-Blundell Prism, a clay prism housed in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The text’s purpose seems to be to demonstrate a single, continuous line of authority passed down through the ages.

Its opening line sets a divine and authoritative tone:

“After the kingship descended from heaven, the kingship was in Eridu.”

This single sentence establishes the core concept of the entire document: kingship (nam-lugal in Sumerian) is not a human invention but a divine institution. It is bestowed by the gods upon a single city at a time. When one city falls, kingship is transferred to another, creating a sequential chain of command over Mesopotamia. This unique perspective helps explain why the list doesn’t mention contemporaneous dynasties ruling at the same time—in the list’s ideological view, only one city could hold legitimate kingship at any given moment.

The Antediluvian Rulers: An Age of Myth

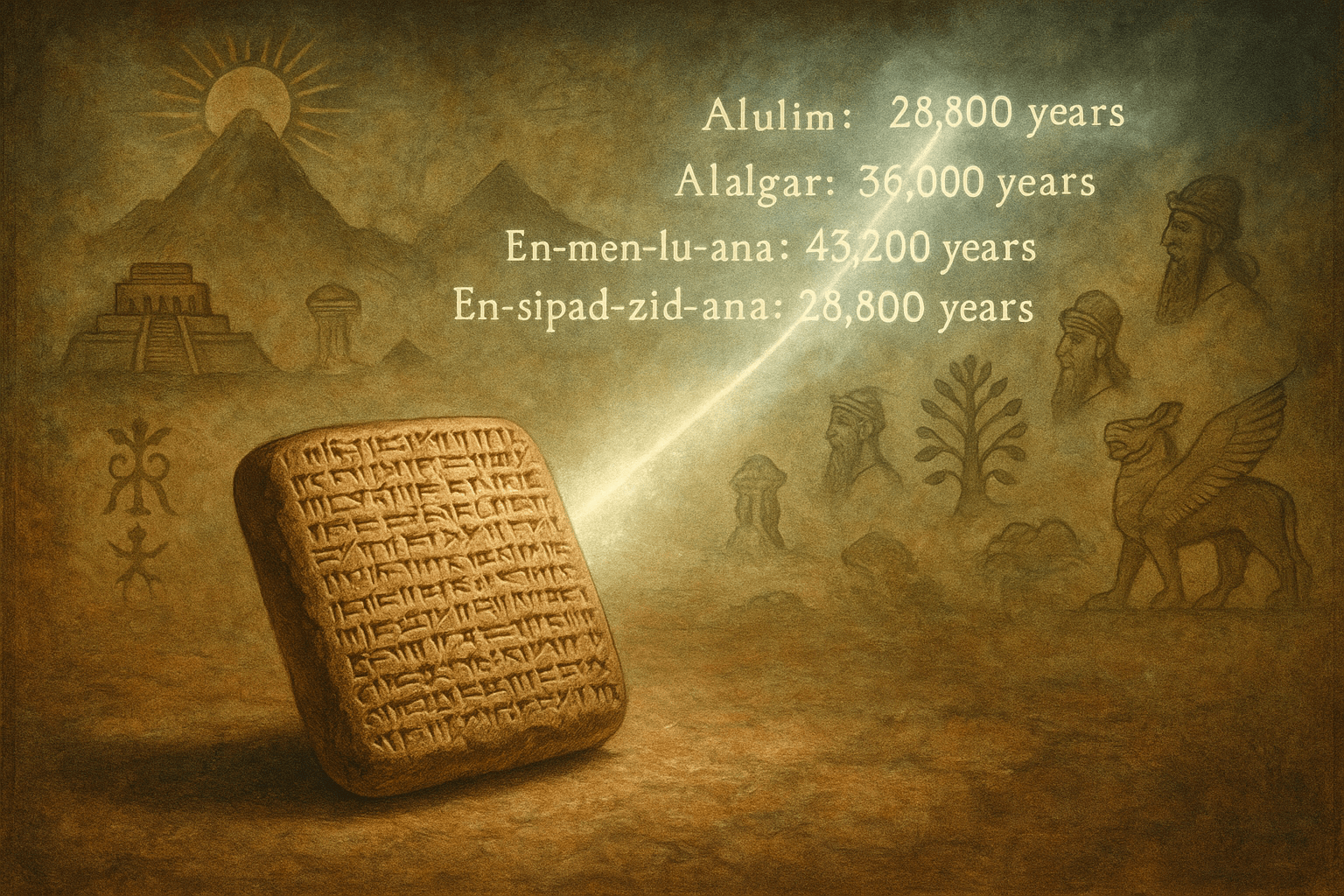

The most captivating and debated section of the SKL is its beginning, which details the rulers before the Great Flood. These are the Antediluvian Kings. The list names eight kings who ruled from five different cities over a staggering period of 241,200 years.

The lineage begins in Eridu, a city the Sumerians believed to be the first in the world, the home of the wise god Enki:

- Alulim of Eridu reigned for 28,800 years.

- Alalgar of Eridu reigned for 36,000 years.

After Eridu “fell”, the kingship moved to the city of Bad-tibira, where three more kings reigned for a combined 108,000 years. One of these figures is Dumuzid, the Shepherd, a deity familiar from other Sumerian myths as the husband of the goddess Inanna. His inclusion blurs the line between god and king, suggesting that these early rulers were seen as semi-divine beings living in a mythical “golden age.”

The kingship then passes through Larak, Sippar, and finally to Shuruppak. The last antediluvian king is Ubara-Tutu of Shuruppak, whose son, Ziusudra, is the hero of the Sumerian flood story—a parallel to the biblical Noah.

“Then the Flood Swept Over”

The list marks a stark turning point with a simple, powerful phrase:

“Then the flood swept over.”

This line acts as a great reset button for civilization. The world of demigods and impossibly long reigns is washed away. The flood narrative was a cornerstone of Mesopotamian mythology, most famously appearing in the Epic of Gilgamesh. In the SKL, it serves as the boundary between a sacred, mythical past and a worldly, political present. Everything that came before is part of a lost, dreamlike era; everything that comes after is the foundation of the world the list’s scribes knew.

After the flood, the text states that kingship once again “descended from heaven”, this time to the city of Kish. This re-establishment of divine order signifies a new beginning for humanity.

Making Sense of the Impossible Numbers

No historian believes that Alulim ruled for 28,800 years. So, what do these numbers mean?

- Symbolism Over Literalism: The antediluvian reigns were not meant to be taken as literal history. They were symbolic, intended to convey a sense of immense antiquity and the sacred, otherworldly nature of the pre-flood era. The sheer scale of the numbers elevates these first kings far above mortal men.

- Propaganda and Legitimacy: The Sumerian King List was likely compiled during the Isin Dynasty (c. 2017-1794 BCE). By creating a document that traced kingship in an unbroken line from the gods themselves down to their own time, the rulers of Isin were creating a powerful piece of political propaganda. They were claiming to be the rightful heirs to a tradition that began at the dawn of time.

- Sumerian Numerology: The Sumerians used a sexagesimal (base-60) number system, parts of which we still use today for time (60 seconds, 60 minutes) and circles (360 degrees). The large numbers in the list are often multiples of 60 and 3600 (60²), a unit known as a šār. These were not random figures but numbers with deep cultural and mathematical significance, used to express concepts of “totality” and “epic” time spans.

From Myth to History

One of the most remarkable aspects of the SKL is its gradual transition toward reality. After the flood, the reign lengths of the kings of Kish, while still exaggerated (the first, Jushur, is said to have ruled for 1,200 years), become progressively shorter. Eventually, we encounter figures who are either known from other legends or have been verified by archaeology.

For example, the list names Enmebaragesi of Kish as a king who “carried away as spoil the weapons of the land of Elam.” For a long time, he was thought to be a legend. Then, archaeological discoveries unearthed inscriptions bearing his name, proving he was a real historical ruler from around 2600 BCE. Further down the list is perhaps the most famous Sumerian hero: Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, who is listed as reigning for a more (though still improbable) 126 years.

The inclusion of real, verifiable figures like Enmebaragesi lent immense credibility to the entire document. It retroactively anchored the mythical antediluvian kings to a tangible historical timeline, making the propaganda all the more effective.

A Window into the Sumerian Mind

The Sumerian King List is not a history book to be read for facts and dates. Instead, it is a priceless document that reveals how an ancient civilization constructed its past. It shows us a worldview where history and myth were inseparable, where kingship was a divine gift, and where civilization itself was a fragile order that could be—and once was—wiped out by the will of the gods.

By blending gods, mythical heroes, and real-life rulers into a single, epic narrative, the scribes of ancient Sumer created a foundation story for their entire civilization—a story that legitimized their present by rooting it in a past of unimaginable grandeur.