From Napata to Meroë: A Shift in Power

The story of Meroë is a story of resilience and cultural realignment. For centuries, the Kushite kingdom had its heart at Napata, near the fourth cataract of the Nile. It was from here that powerful Kushite kings, the so-called “Black Pharaohs”, conquered and ruled all of Egypt as the 25th Dynasty. However, relentless conflict with the Assyrians, and later the Persians, forced the Kushites out of Egypt by the 7th century BCE.

This push Gsve birth to a new chapter for the kingdom. Gradually, the center of power shifted southward to Meroë, which officially became the capital around 300 BCE. This move was a strategic masterstroke. Meroë was less vulnerable to incursions from its northern neighbors and was perfectly positioned to capitalize on sub-Saharan trade routes. More importantly, the region was rich in two resources that would define the city’s destiny: iron ore and the acacia forests needed to fuel its forges. This southward shift also allowed Kushite culture to evolve, blending its Egyptian-influenced past with more distinct, indigenous African traditions.

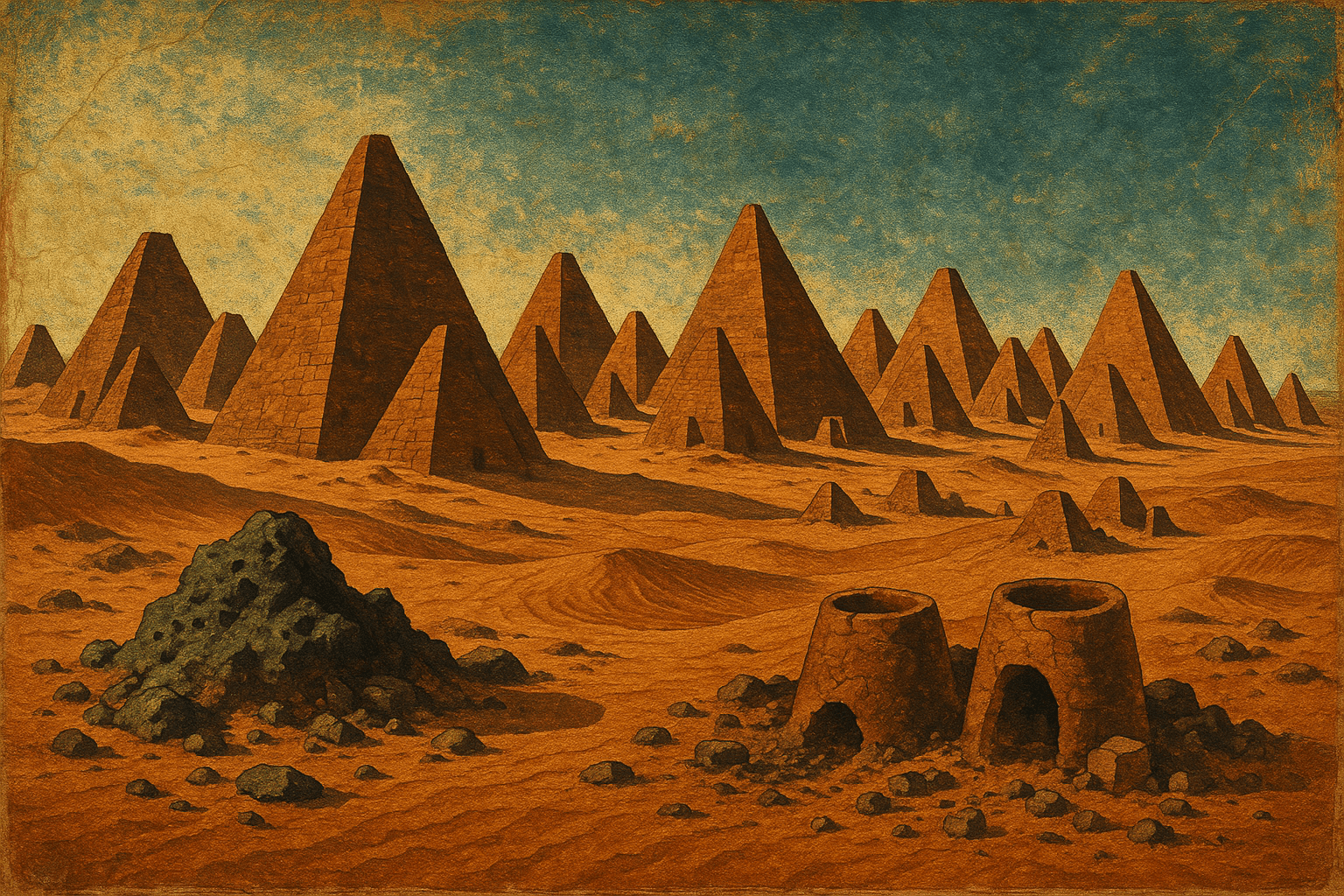

The Necropolis of a Kingdom: The Steep Pyramids of Meroë

The most striking visual legacy of Meroë is its royal necropolis. Over 200 pyramids are clustered here, a breathtaking sight against the desert backdrop. But these are not the massive, limestone-cased structures of Giza. Meroitic pyramids are a distinctly Kushite creation:

- Steep and Narrow: They are dramatically smaller than their Egyptian counterparts, rising sharply with angles between 70 and 80 degrees, giving them a unique, pointed appearance.

- Nubian Sandstone: Built from local reddish-brown sandstone, they glow with a warm hue in the rising and setting sun.

- Adjoining Chapels: Each pyramid has a small funerary chapel built against its eastern face. These were not hidden but were places for offerings and remembrance.

The reliefs carved into these chapel walls offer a fascinating glimpse into Kushite belief. Here, Egyptian gods like Amun and Osiris stand alongside the powerful indigenous lion-headed god, Apedemak. These pyramids were the final resting places for Meroitic royalty—not just kings, but also the powerful ruling queens known as Kandakes (or Candaces). These warrior-queens held immense authority, sometimes ruling alone, and were buried with the same honors as their male counterparts.

Tragically, the necropolis suffered immense damage in the 1830s at the hands of the Italian explorer and treasure hunter Giuseppe Ferlini. Believing the pyramids held vast golden treasures, he blasted the tops off over 40 of them, including the pyramid of Kandake Amanirenas, destroying irreplaceable history for a handful of jewelry.

The “Birmingham of Africa”: An Industrial Powerhouse

While the pyramids testify to Meroë’s royal power, it was industry that fueled its economy. Archaeologists have dubbed Meroë the “Birmingham of Africa” for its colossal iron production. In an age when iron meant wealth and military dominance, Meroë was a superpower.

The city’s smelters worked for centuries, producing high-quality iron tools, weapons, and trade goods. The evidence of this vast enterprise is still visible today in the form of enormous mounds of slag—the waste product of smelting. These “iron mountains” are a testament to an industrial operation on a scale unparalleled in ancient sub-Saharan Africa. Meroitic iron was a prized commodity, traded across the continent and via the Red Sea, connecting the African interior with the wider world of India and the Mediterranean.

A Script of Their Own: The Mystery of Meroitic

Perhaps the most tantalizing aspect of Meroë is its language. While the early Kushites used Egyptian hieroglyphs, by the 2nd century BCE they had developed their own unique writing system: Meroitic. This script came in two forms: a formal hieroglyphic style for monuments and a flowing cursive script for everyday use.

Herein lies the great mystery. Scholars, most notably the British Egyptologist Francis Llewellyn Griffith, successfully deciphered the script in the early 20th century. We know the phonetic values of its 23 letters; we can essentially “read” Meroitic texts out loud. However, the underlying language itself remains almost completely unknown. It appears unrelated to ancient Egyptian or any modern language in the region.

Imagine being able to read the letters of a sentence in Russian or Japanese but having no idea what the words mean. That is the challenge facing historians today. We can identify names of kings, queens, and gods, as well as some formulaic expressions in funerary texts, but the broader story contained in these inscriptions remains locked away, waiting for a linguistic key that has yet to be found.

The Twilight of a Great City

After nearly a millennium of influence, Meroë’s power began to wane around the 4th century CE. The reasons for its decline were likely multifaceted. Centuries of intensive iron smelting may have led to widespread deforestation and environmental degradation, depriving the city of the fuel it needed. Simultaneously, its economic position was challenged. The rise of the Roman Empire shifted trade patterns in the north, and a powerful new rival emerged to the east: the Kingdom of Aksum in modern-day Ethiopia.

A triumphant stone inscription left by King Ezana of Aksum claims that he conquered and sacked Meroë, scattering its people. While the city may have already been in decline, this invasion likely delivered the final blow. The great city on the Nile fell silent, its unique script fell out of use, and its memory was slowly buried by the desert sands.

Today, as a UNESCO World Heritage site, Meroë stands as a powerful reminder of the rich and complex history of ancient Africa. It is a testament to a civilization that forged its own path, creating a unique culture, a powerful industry, and a mystery that continues to captivate us, all in the shadow of its more famous northern neighbor.