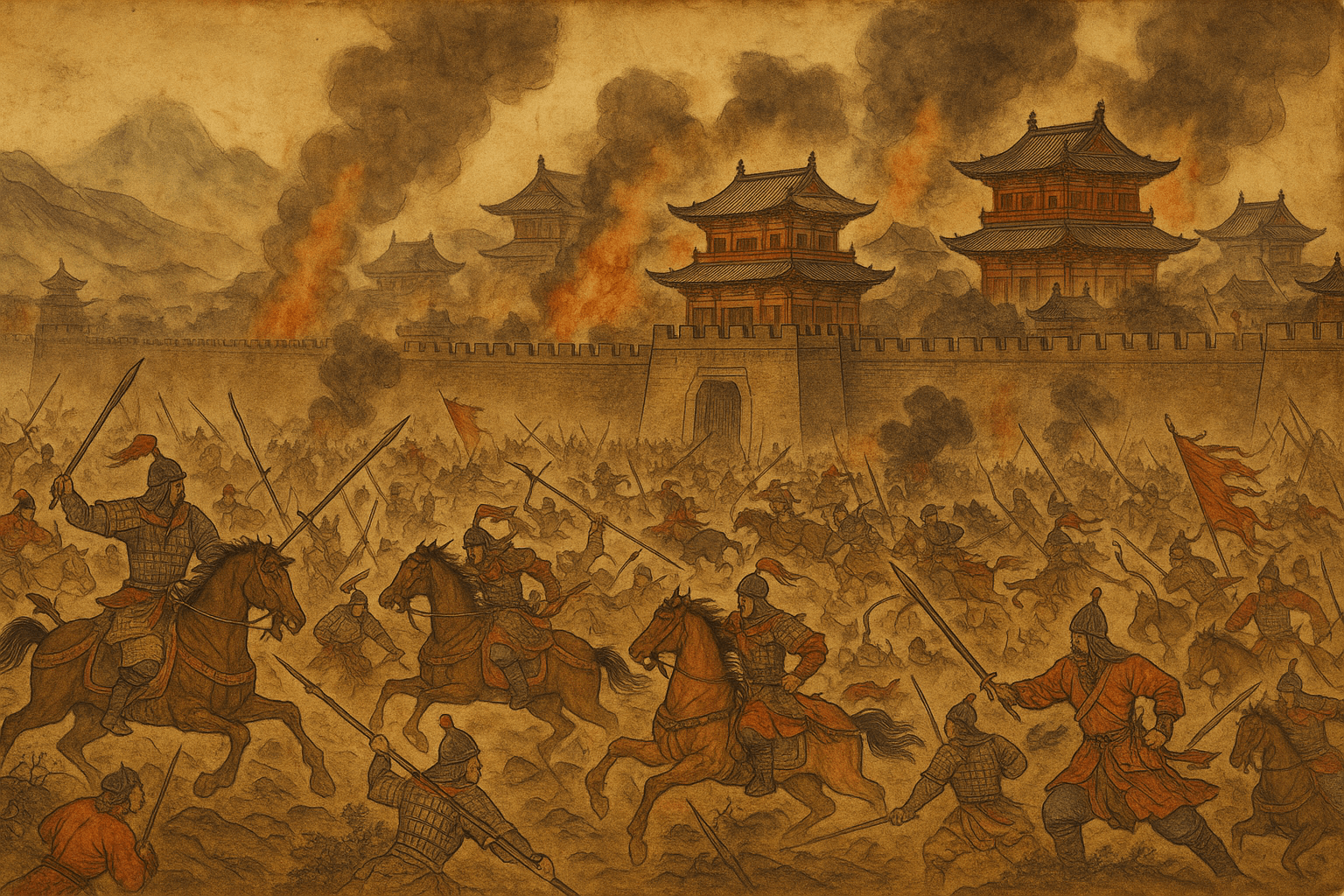

Imagine a world of breathtaking power, cultural brilliance, and immense wealth. This was the Tang Dynasty of China in the mid-8th century, a realm that stretched from the Korean peninsula to the deserts of Central Asia. Its capital, Chang’an, was the most populous and cosmopolitan city on Earth, a dazzling hub where silk-laden camels from the West mingled with poets, scholars, and officials in gilded halls. At the center of it all sat Emperor Xuanzong, the “Brilliant Emperor”, whose long reign had overseen this golden age. But beneath the shimmering surface, a storm was gathering—one that would not just tarnish this golden age, but shatter it completely.

This cataclysm was the An Lushan Rebellion, an eight-year conflict (755-763 CE) that ripped the empire apart, caused the deaths of millions, and irrevocably altered the course of Chinese history. It is a story of ambition, betrayal, and the catastrophic collapse of a superpower.

The Ambitious General and the Aging Emperor

The rebellion’s namesake, An Lushan, was one of the most fascinating figures of the era. Of mixed Sogdian and Turkic descent, he was a physically imposing man from the frontier—a world away from the refined aristocrats of the capital. He was cunning, politically astute, and a skilled flatterer. Through a combination of military success on the northern border and a carefully crafted persona, he worked his way into the emperor’s inner circle.

By this time, Emperor Xuanzong was in his 60s, increasingly detached from the tedious work of governing and infatuated with his consort, the legendary beauty Yang Guifei. An Lushan expertly exploited this situation. He charmed the aging emperor, who saw him as a loyal, if uncultured, servant. He even managed to have himself “adopted” as a son by Yang Guifei, performing bizarre ceremonies in which the massive general would appear before her dressed as a baby. The court laughed, but behind the farce, An Lushan was accumulating unprecedented power.

Emperor Xuanzong granted him the title of jiedushi, or military governor, over three crucial northern regions. This gave An Lushan command of the largest and most battle-hardened army in the empire—a force of nearly 200,000 men who were loyal not to the Tang state, but to him personally.

The Spark That Lit the Empire Ablaze

While An Lushan cultivated the emperor’s favor, he made a powerful enemy: Yang Guozhong, the cousin of Yang Guifei and the empire’s chancellor. The two men despised each other, and their rivalry became the defining political conflict of the court. Yang Guozhong, sensing the danger of An Lushan’s growing military might, repeatedly warned the emperor, but Xuanzong, blinded by his affection for his “loyal” general, dismissed the concerns.

In late 755, the breaking point was reached. Feeling cornered by Yang Guozhong’s political maneuvering, An Lushan made his move. Declaring he had a secret imperial directive to remove the “traitor” Yang Guozhong, he marched his massive army south. He named his new dynasty “Yan”, and the rebellion began.

The initial advance was terrifyingly swift. The professional frontier army of An Lushan smashed through the unprepared imperial defenses. The great eastern capital, Luoyang, fell within a month. The meticulously constructed Tang state, which had seemed so invincible, began to crumble like porcelain.

The Fall of Chang’an and a Dynasty’s Humiliation

By the summer of 756, the rebel army was approaching the main capital, Chang’an. Panic seized the court. Emperor Xuanzong, now over 70, was forced to flee his own capital with his family and a few loyal guards. It was a scene of utter humiliation.

The flight turned to tragedy at a small outpost called Mawei Inn. The emperor’s starving and mutinous guards, blaming the Yang family for the catastrophe, refused to go on. They seized and executed the hated chancellor, Yang Guozhong. Then, they surrounded the emperor’s quarters and demanded the death of his beloved consort, Yang Guifei. They saw her as the root of the court’s corruption and decay. With his authority shattered and his life on the line, the heartbroken emperor had no choice but to consent. Yang Guifei was strangled by a court eunuch.

This grim episode marked the point of no return. The emperor’s mandate and mystique were gone, and the dynasty was left fighting for its very survival.

A Long, Brutal War and Its Unfathomable Cost

An Lushan’s moment of triumph was short-lived. In 757, he was assassinated by his own paranoid son. Yet the rebellion was far from over. It continued under a succession of brutal leaders, including An Lushan’s former lieutenant, Shi Siming. The war devolved into a grinding, horrific stalemate that consumed the empire for nearly a decade.

The devastation was almost apocalyptic. Historic cities were razed, fertile farmlands were destroyed, and vital infrastructure like the Grand Canal was broken. The human cost was staggering. While precise figures are impossible to verify, the Tang court’s official census records tell a chilling story.

The census of 754 recorded a population of nearly 53 million people. A census taken after the rebellion, in 764, recorded only 17 million.

While this dramatic drop reflects a loss of administrative control as much as actual deaths, historians agree that the war and the subsequent famine, disease, and displacement led to the deaths of tens of millions. It remains one of the deadliest conflicts in human history.

The Legacy of Ruin: A New China

The Tang Dynasty eventually “won” the war in 763, but only by making ruinous compromises. To defeat the rebels, the court had to grant immense authority to other regional military governors, who became warlords in all but name. The state also brought in foreign mercenaries, like the Uyghur Khaganate, who looted the recaptured capitals as payment.

The An Lushan Rebellion fundamentally reshaped China. Its legacy included:

- A Weakened Central Government: The emperor was now a figurehead, and real power lay with the jiedushi in the provinces. The dynasty never regained effective control over the entire country, paving the way for its final collapse in 907.

- Economic Collapse: The tax and land systems that had funded the golden age were destroyed. The government resorted to new, harsh taxes and a state monopoly on salt, placing heavy burdens on the peasantry.

- A Shift in Culture: The cosmopolitan, open, and confident spirit of the High Tang was dead. The rebellion, led by a general of “barbarian” origin, fueled a wave of xenophobia. Blame was placed on foreign peoples and influences, and Chinese culture turned inward, becoming more insular and conservative.

The An Lushan Rebellion stands as a stark dividing line in Chinese history. It was the turning point that ended the Tang’s golden age, a period of cultural flourishing and imperial strength. While the dynasty would limp on for another 150 years, it was a shadow of its former self, forever haunted by the memory of a rebellion that had brought the world’s greatest empire to its knees.