The Golden Age City

To understand the depth of the loss, one must first understand what Baghdad was. Founded in the 8th century, the “Round City” was strategically placed at the crossroads of major trade routes. But its true wealth lay in its intellectual capital. The Abbasid caliphs, particularly patrons like Harun al-Rashid and his son al-Ma’mun, championed knowledge above all else.

The legendary House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma) was the epicenter of this intellectual ferment. More than a mere library, it was a translation center, an academy, and a research institute rolled into one. Scholars from across the known world—Muslim, Christian, and Jewish—collaborated to translate the great works of Greece, Persia, and India into Arabic. They didn’t just preserve knowledge; they built upon it, making staggering advances in mathematics (inventing algebra), medicine, astronomy, and optics. While Europe was mired in the Dark Ages, Baghdad was a city of light.

The Storm from the East

As Baghdad flourished, a new power was rising in the east. Genghis Khan had forged the scattered Mongol tribes into an unstoppable military machine that, by the mid-13th century, had carved out the largest contiguous land empire in history. His grandson, Hulagu Khan, was tasked by the Great Khan Möngke with a clear mission: subdue the lands of Western Asia, from Persia to the Mediterranean.

Hulagu was a brilliant and utterly ruthless commander. Before marching on Baghdad, he first destroyed the legendary mountain fortress of Alamut, the stronghold of the fearsome Order of Assassins, a feat no one had managed before. His message was clear: no one was safe. Submission or annihilation were the only options.

A Caliph’s Fateful Miscalculation

The man on the Abbasid throne was Caliph Al-Musta’sim. He was, by most accounts, a man more interested in poetry and leisure than statecraft. When Hulagu Khan sent envoys demanding submission, Al-Musta’sim responded with a mix of arrogance and naivety. He refused to bow, threatening the Mongol leader with the wrath of the entire Muslim world, which he foolishly believed would rally to his cause. He boasted that his city was divinely protected.

It was a disastrous misreading of the situation. The Caliph’s political power was largely symbolic by this point, and his military was a shadow of its former glory. He failed to muster his full army, failed to reinforce the city’s walls, and failed to see the existential threat barrelling toward him. He had chosen defiance without preparing for war.

The Siege and Annihilation

In January 1258, Hulagu’s massive army, perhaps 150,000 strong and bolstered by Christian allies from Georgia and Armenia, arrived at the walls of Baghdad. The Mongols were masters of siege warfare. They built a palisade and ditch around the entire city, brought up powerful catapults, and began a relentless bombardment.

The Caliph’s small army was quickly overwhelmed. On January 29th, the assault began in earnest. By February 10th, the city surrendered. Hulagu initially feigned a withdrawal, luring the city’s remaining soldiers out, where they were trapped and massacred.

On February 13th, the sack began. For seven days, the Mongols pillaged, burned, and killed with an inhuman fury. What followed was a week of unimaginable horror. Palaces, hospitals, mosques, and centuries of accumulated architectural wonder were reduced to smoldering ruins. The population was systematically butchered. Estimates of the dead range from 200,000 to over a million people. The stench of death was so overwhelming that Hulagu had to move his camp upwind from the city.

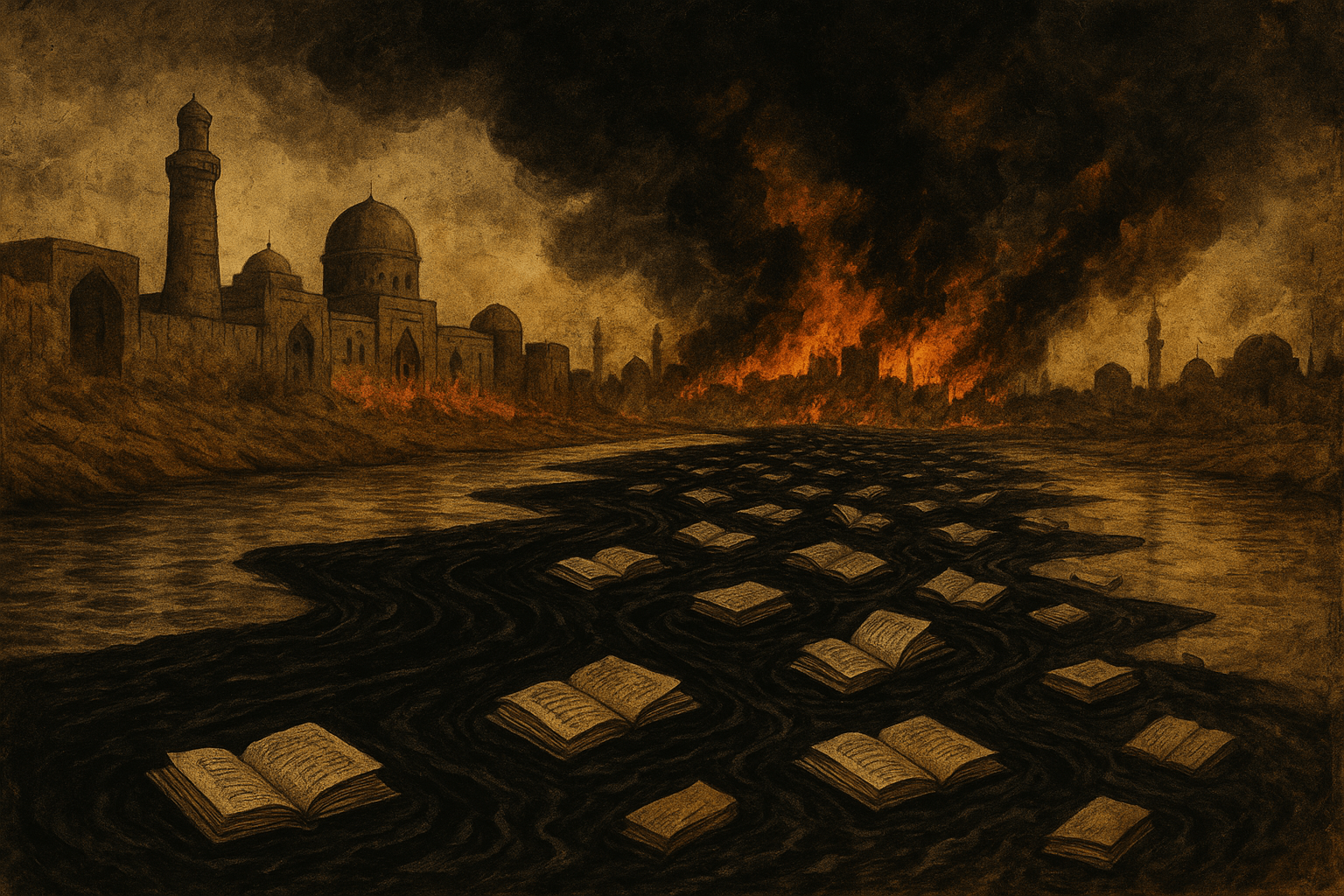

The most devastating blow, however, was cultural. The great libraries of Baghdad, including the House of Wisdom, were utterly destroyed. Eyewitness accounts describe a scene of heartbreaking loss:

“They swept through the city like hungry falcons attacking a flight of doves, or like raging wolves attacking sheep… The books from the city’s treasuries of knowledge were thrown into the Tigris. So many books were cast into the river that they formed a bridge that one could walk across, and the water, which had been clear, was dyed black by the ink of the manuscripts.”

Another account famously states that the river ran black with ink from the countless destroyed books, and then red with the blood of the slaughtered scholars.

The Aftermath: A World in Ashes

The Sack of Baghdad ended more than just a city; it ended an era. The consequences were profound and long-lasting.

- The End of the Islamic Golden Age: While the Golden Age was arguably already in decline, the destruction of its intellectual heart was a final, fatal blow. The loss of innumerable scientific texts, philosophical treatises, and literary works was a setback from which the intellectual world of Islam would never fully recover. The center of Islamic power and learning shifted to Mamluk Egypt and other regions.

- Political Collapse: Caliph Al-Musta’sim was captured and, according to legend, rolled in a carpet and trampled to death by horses—a Mongol custom for executing royalty without spilling their blood. His death marked the end of the 500-year-old Abbasid Caliphate, a powerful symbol of Sunni unity.

- Ecological Devastation: The Mongols also destroyed the vast and ancient canal network that had irrigated the Mesopotamian plains for thousands of years. This act of strategic vandalism turned fertile farmland into a swamp and then into a desert, crippling the region’s agricultural base for centuries.

The fall of Baghdad in 1258 stands as a chilling reminder of the fragility of civilization. It shows how centuries of progress, learning, and culture can be obliterated in a matter of days by violence and hubris. It was a turning point in history, a moment when a world of light and learning was plunged into an abyss of fire and blood, forever changing the trajectory of the Middle East and the world.