Imagine stepping into a 19th-century parlor. Amidst the velvet curtains and gas lamps, a practitioner gently runs their fingers over your scalp, pausing, measuring, and consulting a detailed chart. After a few moments of intense concentration, they declare that you possess a strong sense of “amativeness” (romantic love) and “philoprogenitiveness” (parental love), but could stand to develop your faculty for “veneration” (reverence). This wasn’t a fortune-teller’s gimmick; it was a session of phrenology, the wildly popular but ultimately debunked “science” of reading the mind by examining the shape of the skull.

For much of the 19th century, phrenology captivated the public imagination in Europe and America. It presented itself as a revolutionary, modern key to unlocking the secrets of human character. While we now dismiss it as a classic pseudoscience, its story is a fascinating and cautionary tale about the allure of easy answers, the public’s thirst for self-knowledge, and the dark ways that flawed science can be used to justify prejudice.

The Brain Mapped: The Origins of Phrenology

The story of phrenology begins not with a quack, but with a serious and respected physician: Franz Joseph Gall. In the 1790s, the Viennese doctor put forth a series of radical—and in some ways, prescient—ideas. Gall proposed that:

- The brain, not the heart, was the organ of the mind.

- The mind was not a single entity but was composed of multiple distinct mental “faculties.”

- Each faculty was housed in a specific region, or “organ”, of the brain.

- The size of an organ was a direct measure of its power.

- Crucially, the skull hardened over the brain during infancy, preserving its shape. Therefore, the external contours of the skull reflected the size and power of the underlying mental faculties.

This was Gall’s doctrine of “organology.” He spent years observing people—prisoners, students, asylum patients—and linking their behaviors to specific bumps or depressions on their heads. It was his charismatic associate, Johann Spurzheim, who would later popularize the system, coin the term “phrenology” (from the Greek phrēn for ‘mind’ and logos for ‘study’), and transform it into an international phenomenon.

From the Salon to the Street Corner: Phrenology’s Popular Appeal

Phrenology was a smash hit. It perfectly captured the 19th-century zeitgeist, a period of immense industrial change, scientific discovery, and a burgeoning belief in self-improvement. For the average person, it offered something for everyone.

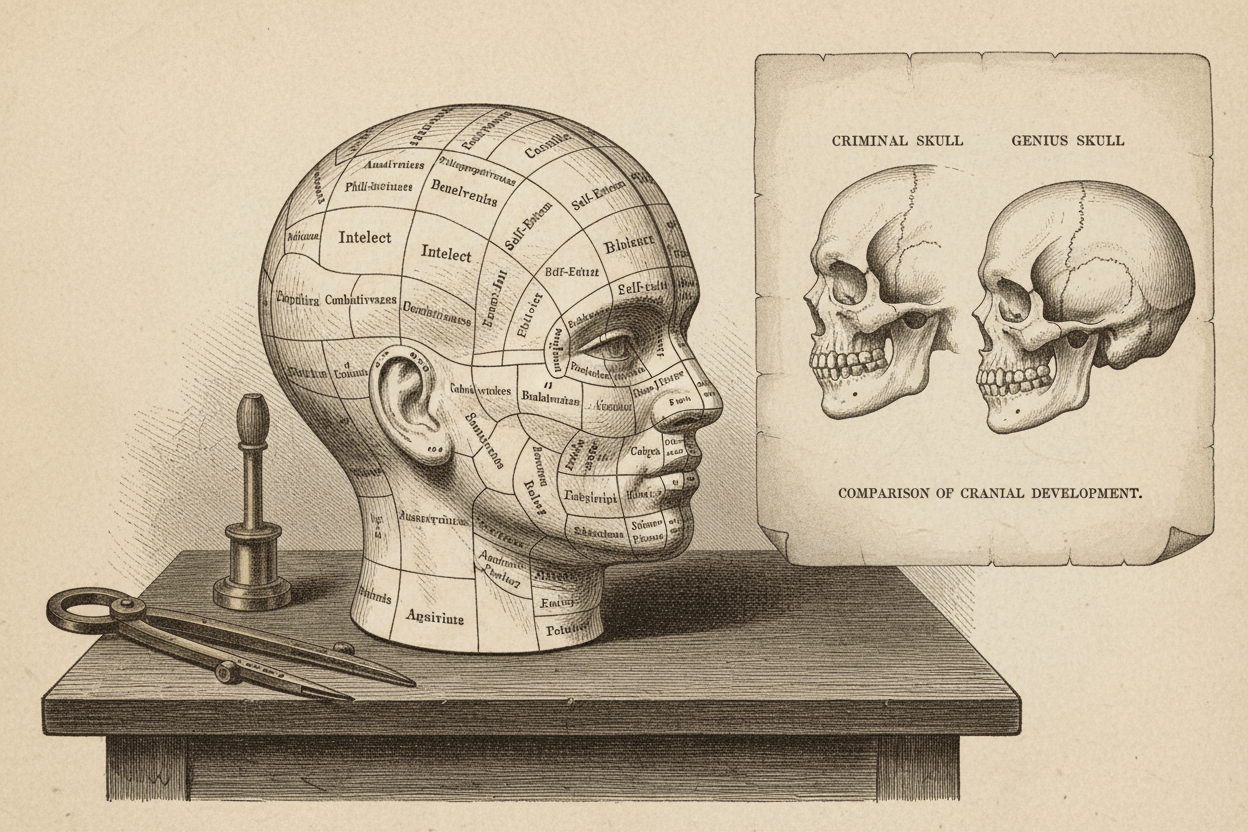

First, it felt scientific. Practitioners used calipers, detailed charts, and a complex lexicon of Latinate terms. The iconic porcelain busts, with the head sectioned into dozens of faculties like “Sublimity”, “Acquisitiveness”, and “Secretiveness”, lent the practice an air of medical authority. Second, it promised practical application. Wondering if a potential spouse was faithful? A phrenologist could check their “Adhesiveness” and “Inhabitiveness” bumps. An employer might have a candidate’s head read to assess their “Conscientiousness.” Parents even had their children’s skulls examined to guide their education, encouraging them to “exercise” weaker faculties and suppress overactive ones.

Famous figures and intellectuals were swept up in the craze. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert had a phrenologist examine their children’s heads. The poet Walt Whitman was a devoted believer, writing that an assessment of his own head confirmed his “leading traits.” Mark Twain humorously chronicled his own conflicting phrenological readings, noting how one practitioner found a “mountain” of humor where another had found a “cavity.” Phrenology became a parlor game, a self-help guide, and a career-counseling service all rolled into one.

A Shadowy Legacy: Criminology and Scientific Racism

While much of phrenology’s appeal was benign, its application took a much darker turn. As it gained credibility, it was adopted as a tool to explain and justify social hierarchies, particularly in the fields of criminology and race theory.

Phrenologists like George Combe in Scotland argued for the existence of a “criminal head”, characterized by large organs of “Destructiveness” and “Acquisitiveness” and small organs of “Benevolence” and “Veneration.” This biological determinism suggested that some individuals were simply “born criminals”, their fates sealed by the shape of their skulls. This idea had a profound and dangerous influence on early criminology, shifting focus away from social causes of crime and towards the supposed innate degeneracy of certain individuals.

Even more sinister was phrenology’s role in the development of “scientific racism.” In the United States, prominent physicians like Samuel George Morton used phrenological principles to create a racial hierarchy based on skull measurements. Morton amassed a huge collection of skulls from around the world. By measuring their cranial capacity and analyzing their “phrenological developments”, he and his followers “proved” what white society already wanted to believe: that Caucasians were intellectually and morally superior, possessing larger faculties for intellect and reflection. Conversely, they claimed that the skulls of Native Americans and Africans showed larger “animal propensities” and smaller intellectual organs, providing a supposedly scientific justification for slavery, segregation, and colonialism. Phrenology gave prejudice the veneer of objective fact.

The Unraveling of a ‘Science’

From its inception, phrenology faced skepticism from the mainstream scientific community. French physiologist Pierre Flourens conducted experiments on animal brains in the 1820s, showing that specific functions were not nearly as localized as Gall claimed and that the brain often worked as a holistic system. More damningly, he demonstrated that the contours of the skull did not match the contours of the brain beneath.

The “faculties” themselves were arbitrary and impossible to falsify. If a kind person had a small bump of “Benevolence”, a phrenologist could simply explain it away by claiming that other faculties were compensating for it. The system was endlessly flexible and self-confirming. As the 19th century progressed, true neuroscience began to advance. The study of patients with brain injuries, like the famous case of Phineas Gage whose personality changed dramatically after an iron rod pierced his frontal lobe, provided real evidence for the localization of brain function—evidence that bore no resemblance to a phrenologist’s chart.

By the turn of the 20th century, phrenology was thoroughly discredited within scientific and medical circles. It was relegated to the realm of fairground entertainment and quackery, a ghost of a science that had once promised to read the human soul.

Today, the porcelain phrenology head is little more than a curious antique. But its story serves as a powerful historical lesson. It reminds us that ideas dressed in the language of science can be immensely powerful, whether they are true or not. Phrenology’s rise and fall illustrate our enduring desire to understand ourselves, but also stand as a stark warning against the danger of pseudoscientific beliefs, especially when they are used to build hierarchies and justify inhumanity.