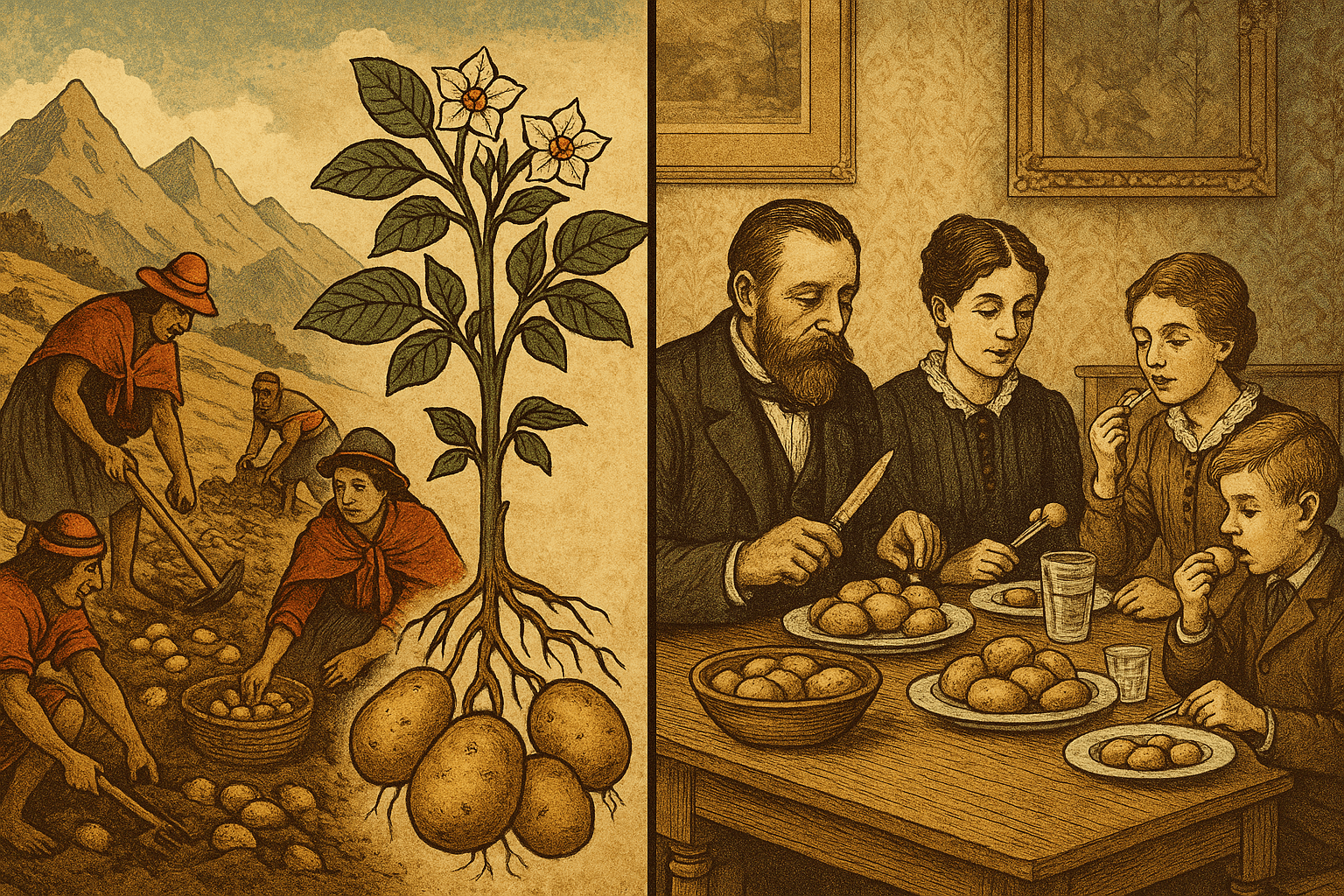

Few foods are as common, as comforting, or as universally recognized as the potato. Whether mashed, fried, baked, or boiled, it’s a staple on tables across the globe. But to see the potato as a mere side dish is to miss one of the most dramatic stories in world history. This unassuming tuber, born high in the Andes mountains, is a quiet protagonist in the tale of the modern world—a force that fueled empires, fed revolutions, and tragically, brought a nation to its knees.

A Treasure from the Andes

The potato’s story begins not in Ireland or Germany, but in the soaring altitudes of the Andes mountains in South America, nearly 8,000 years ago. Long before the rise of the Inca Empire, ancient peoples in modern-day Peru and Bolivia had domesticated the wild potato. For these civilizations, the potato was not just food; it was the bedrock of their existence.

In a landscape where corn and wheat couldn’t survive the harsh conditions, the potato thrived. The Andean people cultivated thousands of varieties, a stunning rainbow of colors, shapes, and sizes adapted to different microclimates. They even developed a brilliant preservation method, creating chuño—freeze-dried potatoes—by exposing them to the freezing mountain nights and sunny days. This allowed them to store food for years, providing a crucial buffer against famine and enabling complex societies like the Inca to flourish.

Europe’s Cautious Welcome

When Spanish conquistadors arrived in the 16th century, they were more interested in gold and silver than in local agriculture. Still, they brought the potato back to Spain around 1570 as part of the vast ecological transfer known as the Columbian Exchange. But Europe was not impressed.

The potato was met with deep suspicion and outright fear. Here’s why:

- It was foreign: The potato wasn’t mentioned in the Bible, a serious mark against it in a devoutly religious era.

- It was ‘unclean’: It grew underground, which many associated with dirt and impurity.

- It was a Nightshade: As a member of the nightshade family, which includes poisonous plants like belladonna, many botanists and physicians wrongly declared it toxic, blaming it for everything from leprosy to scrofula.

For nearly two centuries, the potato remained a botanical curiosity, grown in the gardens of the wealthy, or at best, used as animal feed. It was considered the food of the desperate, not of civilized society.

Fueling an Industrial and Military Revolution

So what changed? In a word: desperation. The 18th century was a period of constant warfare and volatile food supplies in Europe. Armies marching across the continent routinely burned grain fields, leading to widespread famine. But the potato had a secret weapon: it grew underground, safe from the ravages of soldiers.

Enlightened rulers and thinkers began to see its potential. In Prussia, Frederick the Great, facing food shortages during the Seven Years’ War, ordered his peasants to plant potatoes. When they resisted, he famously employed reverse psychology, posting royal guards around his potato fields to make the crop seem valuable and desirable. In France, an army pharmacist named Antoine-Augustin Parmentier, who had survived on a diet of potatoes as a prisoner of war in Prussia, became the plant’s greatest champion. He hosted lavish dinners for French elites featuring only potato dishes, eventually winning over King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

Once adopted, the potato’s impact was explosive. It provided an abundant source of calories and vital nutrients, including Vitamin C, which helped prevent scurvy. A single acre of potatoes could feed far more people than an acre of wheat or rye. The result was an unprecedented population boom across Northern Europe. Between 1700 and 1900, the population of Europe more than doubled, and the potato is credited with being responsible for at least a quarter of that growth. This new, larger population provided the cheap labor needed to power the factories of the Industrial Revolution and the soldiers required to build and maintain colossal colonial empires.

A Monoculture’s Tragic Consequence: The Irish Famine

Nowhere was the potato’s impact more profound—or more tragic—than in Ireland. By the 1840s, the rural Irish poor had become dangerously dependent on it. Oppressive land ownership systems had forced a third of the population to survive on tiny plots of land, where only the potato could provide enough food to feed a family.

Worse, the Irish had come to rely almost exclusively on a single, high-yielding variety: the “Lumper.” This genetic uniformity created a fragile monoculture, ripe for disaster.

Disaster struck in 1845 with the arrival of Phytophthora infestans, or potato blight. This airborne fungus, which likely traveled from North America, turned lush green potato plants into a black, rotting slime almost overnight. The crop failed year after year. The result was the Great Hunger, a famine of unimaginable horror. An indifferent British government did little to help. In less than a decade, more than one million Irish people—one-eighth of the population—died of starvation and disease. Another million were forced to emigrate, scattering across the world and creating a vast Irish diaspora, particularly in the United States. The famine permanently altered Ireland’s demography and culture and remains a stark historical lesson on the dangers of relying on a single food source.

More Than Just a Side Dish

From Ireland, the potato’s story continued its global march. It became a staple in Russia and Poland, and eventually spread to Asia. Today, China is the world’s largest potato producer, and the crop is a cornerstone of food security in many developing nations.

The journey of the potato is a powerful illustration of how a single organism can fundamentally redirect the flow of human history. It fed the poor, empowered kings, fueled industrialization, and built empires. It also exposed the fragility of our food systems, leading to a cataclysm that reshaped nations. So the next time you look at a simple potato, remember the world-altering power hidden within its humble skin. It is, without a doubt, one of history’s greatest agents of change.