Imagine a world without paper. No notebooks, no printer cartridges, no throwaway grocery lists. In this world, every significant word—every law, every sacred prayer, every king’s decree—had to be recorded on a surface built to last for centuries. For over a thousand years, that surface was parchment, the processed animal skin that became the canvas for Western civilization.

The creation of a medieval manuscript, like the stunningly illuminated Book of Kells or a king’s copy of the Magna Carta, didn’t begin in a quiet scriptorium with a scribe. It began in a much louder, smellier, and messier place: the workshop of the percamenarius, the parchment maker. Transforming a bloody, hairy animal hide into a smooth, creamy, and durable writing surface was a masterpiece of craft, a grueling process that was part butchery, part chemistry, and part artistry.

The Right Skin for the Job

Not all skin was created equal. The choice of animal dictated the quality and cost of the final product. The most common sources were the animals most available in a medieval agricultural economy: sheep, goats, and calves.

- Sheepskin: Plentiful and affordable, sheepskin was the workhorse of the parchment world. It has a higher fat content, which can make it feel slightly greasy and less receptive to ink on one side.

- Goatskin: Tougher and with a more visible grain, goatskin produced a sturdy, durable parchment often favored for bindings and official documents.

- Calfskin (Vellum): This was the gold standard. The skin of a young, often newborn or even unborn, calf produced an exceptionally fine, smooth, and pale material known as vellum (from the Old French vélin, for “calf”). Vellum was reserved for the most luxurious and important manuscripts. The famous Gutenberg Bibles, for instance, were printed on both paper and a much smaller, more expensive run on vellum.

The scale of production was staggering. A single large Bible, like the 8th-century Codex Amiatinus, is estimated to have required the skins of over 1,500 individual calves. This wasn’t just a craft; it was an industry with a massive logistical footprint.

Step 1: The Foul-Smelling Soak

Once the fresh hides arrived from the butcher, the real work began. The first step was a thorough washing in a cold, running stream to remove blood, dirt, and dung. After this initial clean, the hides were submerged in a solution that was the stuff of nightmares for the modern nose: a lime bath.

The skins were steeped for several days, sometimes over a week, in wooden vats or stone-lined pits filled with a slurry of slaked lime (calcium hydroxide) and water. The purpose of this caustic bath was twofold:

- It chemically loosened the hair and broke down the epidermis.

- It plumped up the collagen fibers within the skin’s dermis, preparing them for the next stage.

Parchment workshops were famously, powerfully stinky. The combination of decaying organic matter, bacteria, and the sharp chemical smell of lime meant they were usually relegated to the outskirts of town, often downwind and near a river.

Step 2: The Scrape and the Stretch

After their foul soak, the dripping, swollen hides were retrieved. The parchment maker would drape a skin over a large, curved wooden beam and set to work with a special tool: the lunellum, a crescent-shaped knife with a handle in the middle. With skilled, powerful strokes, he scraped away the loosened hair on one side and any remaining flesh and fat on the other. This was physically demanding labor that required a steady hand to avoid gouging the precious material.

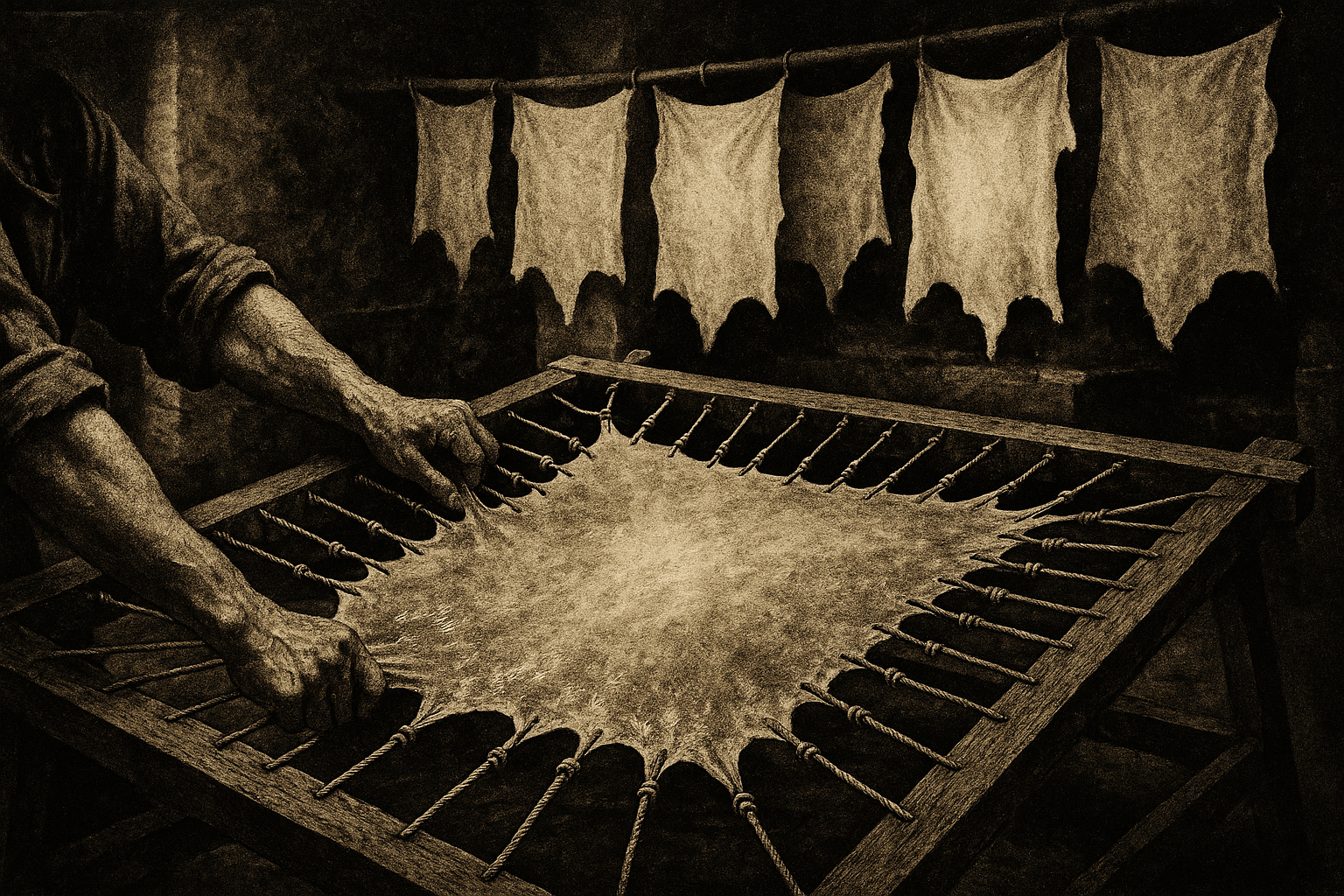

Now came the most critical and defining step in parchment making. The de-haired, cleaned hide was attached to a large wooden frame, called a herse. This wasn’t done with nails. Instead, the parchment maker would wrap small, smooth pebbles in the edges of the wet skin, creating knobs. Cords were looped around these knobs and tied to adjustable pegs on the frame. By twisting the pegs, the maker could apply immense, even tension, stretching the skin from all sides like a drum.

This process of stretching while drying is what fundamentally distinguishes parchment from leather. Tanning leather involves chemical processes that keep the collagen fibers flexible and randomly woven. Stretching parchment under tension forces the collagen fibers to realign into flat, parallel layers. This is what transforms a pliable skin into a stiff, opaque sheet.

Step 3: Refining the Canvas

While the hide was still taut on the frame and drying, the percamenarius went back to work with his lunellum. This second round of scraping was about refinement. He would carefully shave the surface down, thinning the sheet to the desired thickness and evening out any lumps or bumps. This was the moment where true skill shone. Shave too deep, and you create a hole, ruining the entire sheet. Don’t shave enough, and the page is thick and uneven.

The two sides of the skin remained distinct. The “hair side” (where the hair grew) was often slightly darker and might retain visible follicle patterns. The “flesh side” was typically paler and softer. In well-made manuscripts, scribes would arrange the pages so that a hair side always faced another hair side, and a flesh side faced a flesh side, creating a pleasing visual uniformity across a two-page spread.

Once fully dry and scraped to perfection, the surface was still not ready for ink. It was given a final polish by dusting it with powdered pumice and rubbing it vigorously. This abraded the surface just enough to create a fine, velvety nap that would grip the ink and prevent it from bleeding.

From Skin to Scripture

Finally, the large, stiff sheet was cut from the frame. The rough edges were trimmed, and the sheet was typically folded to create a “bifolium”—a single sheet folded in half to make two leaves, or four pages, of a book. These bifolia would be nested together to form gatherings, or quires, which were then sewn together to form the final codex.

Even then, the scribe had one last preparation. He might dust the page with “pounce”, a fine powder of chalk or crushed cuttlefish bone, to further degrease the surface. Then, using a sharp point, he would rule faint, invisible lines to guide his hand, ensuring the sacred words would flow across the page in perfect, ordered harmony.

From a living, breathing animal to a luminous page in a holy book, the journey of parchment was a testament to human ingenuity and labor. Its durability is the reason we can still read the words of Caesar, marvel at the artistry of the Lindisfarne Gospels, and study the foundations of Western law. Every time you see a medieval manuscript, remember the stench, the sweat, and the incredible skill that went into creating the very surface it was written on. It’s a tangible link to a past written not on flimsy paper, but on the very fabric of the animal world.