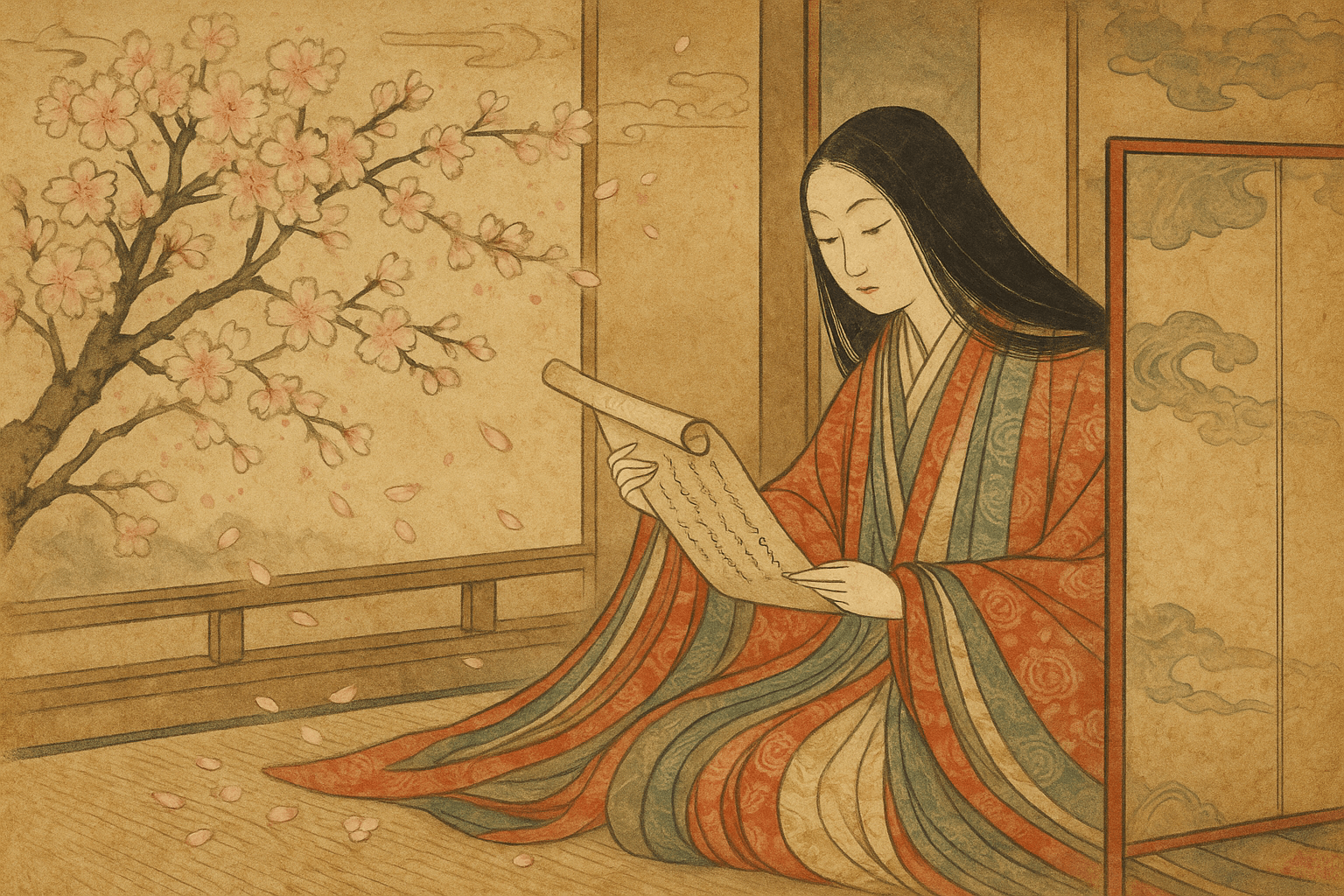

Imagine a world bathed in moonlight, where the rustle of silk is a language and a perfectly composed poem is more potent than a sword. This was not a dream, but the reality for the elite of Heian-era Japan (794-1185 AD). Centered in the magnificent capital of Heian-kyō (modern-day Kyoto), the imperial court cultivated a society of such extreme refinement and aesthetic sensitivity that it remains one of the most fascinating periods in world history. This was the world of Murasaki Shikibu’s masterpiece, The Tale of Genji, a “floating world” where life itself was the highest form of art.

A World Enclosed: Life in Heian-kyō

The Heian court was an exquisitely constructed bubble. The aristocracy, known as the kumo no ue bito or “people above the clouds”, lived lives almost entirely detached from the rest of the country. Their universe was Heian-kyō, a sprawling city laid out on a symmetrical grid modeled after the Chinese Tang capital of Chang’an. At its heart was the Dairi, the Imperial Palace compound, a maze of wooden pavilions, covered corridors, and manicured gardens where the emperor and his court resided.

Life for a courtier was dictated by rank. From the powerful Fujiwara clan, who ruled as regents, down to minor functionaries, one’s position in the hierarchy determined everything: the color of one’s robes, the size of one’s house, eligibility for office, and even the height of one’s gatepost. This insular environment, shielded from the grit and grind of provincial life, allowed for the development of a unique and hyper-stylized culture.

The Currency of Beauty: Miyabi and Mono no Aware

In the Heian court, aesthetic taste was not merely a preference; it was a measure of one’s character and worth. The guiding principle was miyabi (雅), or courtly elegance. It was the absolute imperative to be refined, to eliminate anything vulgar, coarse, or jarring. Miyabi was expressed in every facet of life:

- Fashion: For ladies, the pinnacle of style was the jūnihitoe, or “twelve-layered robe” (though the number of layers varied). The true art lay in the kasane no irome, the color combinations of the visible sleeve edges, which were carefully chosen to reflect the season, a particular flower, or a poetic sentiment. Men, too, wore complex silk robes and lacquered caps, their attire strictly dictated by rank and occasion.

- Appearance: The ideal of feminine beauty involved long, flowing black hair, a chalk-white powdered face, and—most strikingly to modern eyes—shaved or plucked eyebrows that were redrawn higher on the forehead as faint smudges. Both men and women of high rank also practiced ohaguro, the blackening of teeth with an iron-based dye, which was considered a mark of beauty and maturity.

- Accomplishments: A well-bred individual was expected to be proficient in the arts. This meant mastering an instrument like the koto (a zither) or biwa (a lute), possessing elegant calligraphy, and having an encyclopedic knowledge of Chinese and Japanese poetry.

Twinned with miyabi was the concept of mono no aware (物の哀れ), a gentle, melancholic sensitivity to the transient nature of all things. The courtly elite were deeply attuned to the passing of the seasons, seeing in the brief life of a cherry blossom or the mournful cry of a cricket a poignant reflection of their own fleeting existence. This bittersweet aesthetic permeates Heian literature, lending it a distinctive and deeply moving emotional register.

Communication by Poem: The Art of Courtship

In a world where men and women of the upper classes were largely segregated, with women often hidden from view behind screens (sudare) or fans, communication was a delicate and indirect art. Direct speech was often considered too blunt. The preferred medium, especially for romance, was the waka, a 31-syllable poem.

A typical courtship began with a man sending a poem to a lady who had caught his eye. His verse, however, was only part of the message. The entire presentation mattered:

- The paper was carefully selected for its color and texture.

- The calligraphy had to be masterful and stylish.

- A flower or sprig appropriate to the season and the poem’s sentiment was attached.

The lady’s response was just as crucial. Her own poem had to be a clever and graceful reply to his, demonstrating her wit and learning. Her choice of paper and the elegance of her script were scrutinized just as closely. A clumsy verse, poor handwriting, or an inappropriate color of paper could doom a potential romance before it even began. This poetic dialogue, filled with allusions and double meanings, was the lifeblood of Heian social and romantic interaction.

Rituals, Reputation, and the Rise of Women’s Literature

Life was an endless series of rituals and formal events. From seasonal festivals celebrating chrysanthemums or irises to intense competitions in poetry, incense-blending (kōdō), or picture-matching, these were not just leisure activities. They were arenas where reputations were made and broken. A social gaffe—wearing the wrong color robes for the season, for instance—could lead to ridicule and ostracization.

While politically sidelined, court women wielded immense cultural power. Confined to their quarters and largely anonymous to the outside world, they became astute observers of the intricate human drama unfolding around them. With time on their hands and a need for an expressive outlet, women like Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shōnagon turned to writing, creating diaries, collections of essays, and fictional narratives.

Their work, written in the native Japanese script (kana) rather than the official Chinese used by men for government documents, provides our most vivid window into the Heian world. Sei Shōnagon’s The Pillow Book is a witty, sharp-tongued collection of observations and lists, while Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji is a profound novel exploring the romantic exploits and inner life of its “shining prince”, offering a deep psychological portrait of an entire society.

The Fading of the Light

The delicate world of the Heian court could not last forever. While the aristocrats in Kyoto composed poetry and debated the merits of incense blends, power in the provinces was shifting. The court’s authority over the country waned, and a new class of warriors—the samurai—began to rise, prizing martial prowess and loyalty above poetic finesse. The Genpei War (1180-1185) shattered the court’s blissful isolation, ushering in the Kamakura Shogunate and a new feudal era dominated by the samurai. The “people above the clouds” were brought crashing down to earth.

Though its political power vanished, the Heian court’s cultural legacy is immeasurable. Its aesthetic ideals, its literary masterpieces, and its profound sensitivity to beauty and impermanence became foundational pillars of Japanese culture, influencing art, literature, and social etiquette for centuries to come. The world of the shining prince may have faded, but its elegant shadow continues to enchant us today.