The Rise from Cattle Culture

The story of Great Zimbabwe doesn’t begin with a king laying a foundation stone, but with cattle. From around the 4th century AD, Bantu-speaking peoples, the ancestors of the modern Shona, began settling the Zimbabwe plateau. This was prime real estate: well-watered, free from the tsetse fly that plagued lower elevations, and perfect for grazing the cattle that formed the bedrock of their wealth and society.

For centuries, this was a land of smaller chiefdoms. But around 1100 AD, something changed. The chiefdom at the site of Great Zimbabwe began to consolidate power. Its strategic location was key. It lay near the rich goldfields of the interior and was positioned along trade routes that led to the Swahili coast. By controlling the region’s two most valuable resources—cattle and gold—the rulers of Great Zimbabwe laid the groundwork for an empire.

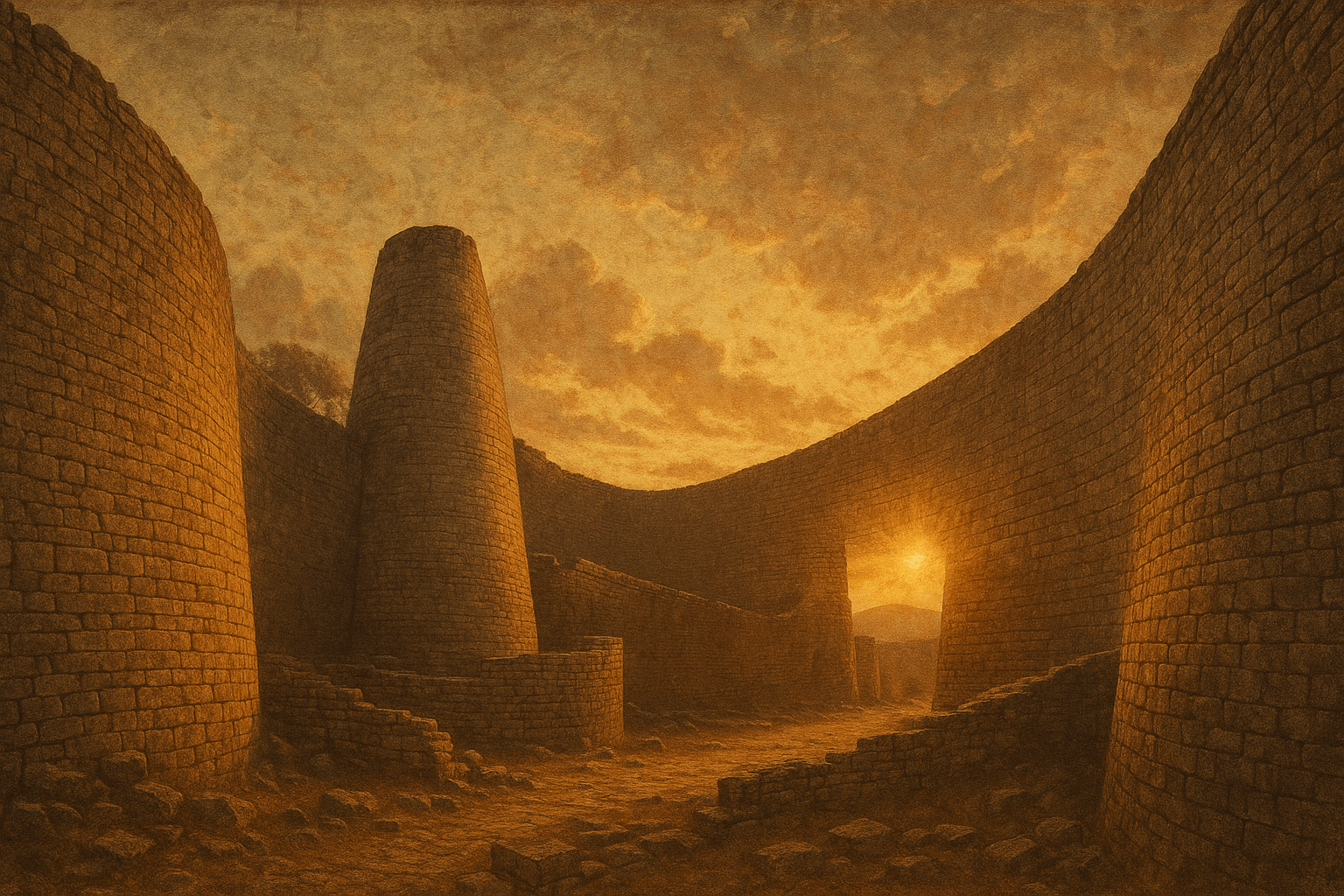

Architectural Marvels Without Mortar

What visitors first notice about Great Zimbabwe are its breathtaking stone structures, all built using a remarkable dry-stone technique. The builders expertly quarried and shaped local granite blocks, fitting them together so perfectly that no mortar was needed for stability. These walls have stood for over 700 years.

The city is generally divided into three main areas:

- The Hill Complex: Perched atop a granite dome, this is believed to be the oldest part of the city and served as its spiritual and royal center. The king likely lived here, in a series of enclosures accessible only through narrow, easily defended passages. Its elevated position offered a commanding view of the surrounding kingdom.

- The Valley Complex: Below the hill, a series of enclosures and daga (a type of clay and gravel cement) huts housed the city’s elite and artisans. It’s here that many significant artifacts, like the famous Zimbabwe Birds, were discovered.

- The Great Enclosure: The most iconic and imposing structure, the Great Enclosure was built in the 14th century, during the city’s golden age. It was not a fortress, but a symbol of the king’s power and prestige. Its outer wall is a masterpiece, running for over 250 meters and reaching a height of 11 meters. Within its walls is the mysterious Conical Tower, a solid stone structure whose exact purpose—be it symbolic of a granary, a phallic symbol of fertility, or a royal emblem—is still debated by historians today.

At its peak in the 14th and 15th centuries, it’s estimated that up to 20,000 people lived in and around this stone metropolis, making it one of the largest cities in the world at the time.

The Engine of a Global Trade Network

Great Zimbabwe was not an isolated kingdom; it was a plugged-in, commercial powerhouse of the medieval world. The king and the ruling elite controlled a vast trade network that stretched from the African interior to the shores of the Indian Ocean and beyond. This wealth, derived not from conquest but from commerce, was the engine of its power.

The kingdom’s chief exports were luxury goods highly prized in the outside world:

- Gold: Sourced from dozens of small mines in the surrounding region, Zimbabwean gold was a major source for the Swahili city-states on the coast and, from there, made its way to Arabia, India, and even China.

- Ivory: Elephant tusks were another valuable commodity, traded for their use in carving and ornamentation across Asia.

- Cattle: While not a long-distance export, the immense herds of cattle represented the true wealth and power of the elite within the kingdom itself.

In exchange, a trove of imported goods found their way to Great Zimbabwe, confirming its international connections. Archaeologists have unearthed fragments of Chinese celadon and porcelain, colorful glass beads from Persia and Arabia, and other exotic items that must have seemed magical to those living on the plateau. This trade made the ruling class spectacularly wealthy, allowing them to fund the construction of the stone city and maintain their authority.

Decline and Enduring Legacy

So why did this magnificent city fall? There was no single, cataclysmic event. By the mid-15th century, Great Zimbabwe began a gradual decline. The reasons are likely a combination of factors. The population may have grown too large for the environment to sustain, leading to deforestation and overgrazing. The nearby gold mines may have become depleted, or, more likely, trade routes shifted north towards the Zambezi River, giving rise to new successor states like the Kingdom of Mutapa.

By the time the Portuguese arrived on the coast in the 16th century, the city was largely abandoned, though it remained a significant spiritual site for Shona people for generations.

Reclaiming a Stolen History

The story of Great Zimbabwe is also a story of a history reclaimed. When European hunters and explorers stumbled upon the ruins in the late 19th century, the prevailing colonial mindset could not accept its African origins. They concocted elaborate, racist theories, attributing its construction to Phoenicians, Egyptians, or the Queen of Sheba—anyone but the local Shona people.

This false narrative was a deliberate tool to justify colonial rule by denying the indigenous population a history of civilization and achievement. It took the methodical work of archaeologists, most notably the British archaeologist Gertrude Caton-Thompson in 1929, to definitively prove the city was of “Bantu origin and medieval date.” Her findings, and all subsequent research, have confirmed that Great Zimbabwe is a purely African achievement.

Today, this powerful history has been fully embraced. The modern nation of Zimbabwe takes its name from the city, and the enigmatic soapstone Zimbabwe Bird, found in the ruins, is the country’s national symbol. Great Zimbabwe is not a mystery of a lost tribe; it is a proud and tangible link to a powerful past, a monument to the genius of the Shona people and a landmark of world history.