While Elizabeth I presided over England’s “Golden Age,” Walsingham was the grim-faced guardian who ensured the nation survived long enough to have one. He was the architect of a vast and terrifyingly effective intelligence network, the unseen hand that protected the Queen from a relentless tide of conspiracies aimed at her life and throne.

The Forging of a Spymaster

To understand Francis Walsingham’s methods, one must first understand his mind. His worldview was forged in the fire of religious persecution. A fervent and uncompromising Protestant, Walsingham fled England during the reign of the Catholic Queen Mary I (“Bloody Mary”). While in exile on the continent, he witnessed firsthand the brutal European Wars of Religion and developed a deep-seated conviction that Catholicism was an existential threat to England and his Protestant faith.

When the Protestant Elizabeth took the throne in 1558, Walsingham returned home with a singular purpose: to protect his queen and his religion from all enemies, both foreign and domestic. Appointed as Principal Secretary in 1573, he held one of the most powerful positions in the government, controlling both foreign and domestic policy. He used this position not just to govern, but to build a state security apparatus the likes of which England had never seen.

Architect of England’s Secret Service

Elizabethan England was a vulnerable nation. It was a relatively new Protestant state surrounded by the Catholic superpowers of Spain and France, both of whom viewed Elizabeth as a heretic and an illegitimate ruler. The ever-present threat was Mary, Queen of Scots, a Catholic with a strong claim to the English throne, who served as a living figurehead for plotters seeking to overthrow Elizabeth.

Walsingham’s response was to go on the offensive. He believed that to defend the realm, he had to know what his enemies were planning before they could act. He established a sprawling network of informants and agents funded, often out of his own pocket, to the tune of thousands of pounds a year. His web stretched across Europe, with paid spies in the major courts of Paris, Rome, Madrid, and Constantinople. He had agents listening for seditious talk in English taverns, students reporting from Catholic seminaries abroad, and contacts on merchant ships watching the movements of foreign fleets.

The Tools of Espionage

Walsingham was a pioneer of modern intelligence gathering, employing methods that were sophisticated and ruthless. His tradecraft was built on a foundation of human intelligence, interception, and analysis.

- A Network of Spies: His agents, known by code numbers rather than names, were a diverse collection of individuals. They included disgruntled courtiers, paid informers, idealistic Protestants, and criminals offered pardons in exchange for information.

- The Use of Double Agents: Walsingham was a master at turning enemy agents into his own. He would capture a conspirator and, under threat of torture or death, “turn” them, forcing them to feed false information back to their original masters while secretly reporting everything to him.

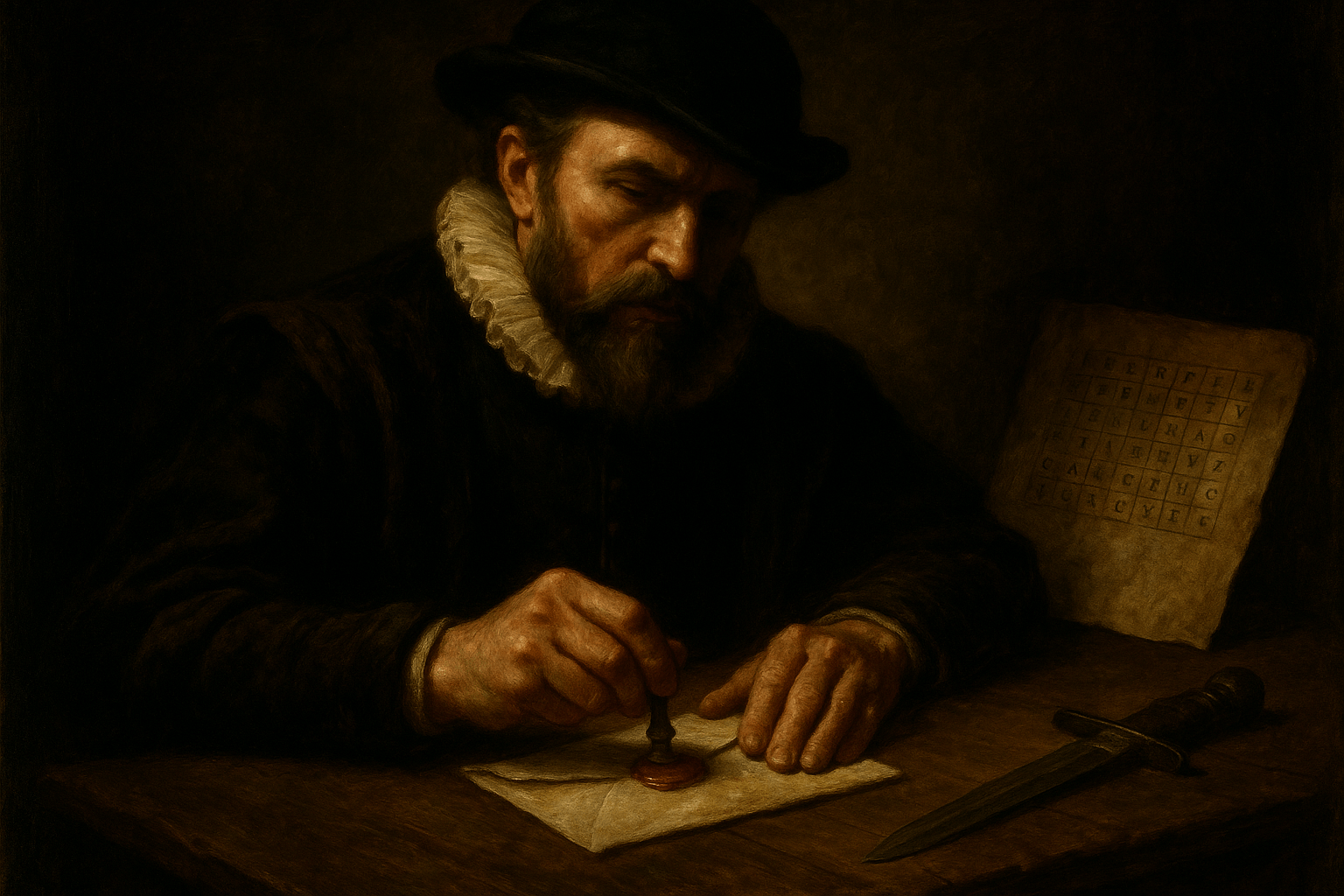

- Interception and Forgery: Walsingham established a “secret chamber” where his agents could intercept mail. His experts became masters of carefully opening sealed letters, copying their contents, and resealing them with forged seals so the recipient would never know their correspondence had been compromised.

- Code-Breaking: The secret to his success was his cryptographer, Thomas Phelippes. A brilliant linguist and mathematician, Phelippes could decipher the complex substitution ciphers used by plotters to conceal their plans. He was Walsingham’s ultimate secret weapon, turning streams of meaningless symbols into damning evidence.

The Ultimate Target: Mary, Queen of Scots

Walsingham’s entire intelligence operation found its ultimate expression in his campaign against Mary, Queen of Scots. For nearly two decades, Mary lived under house arrest in England, a constant magnet for Catholic plots. Walsingham was convinced that as long as Mary lived, Elizabeth would never be safe.

His masterpiece of espionage was the uncovering of the Babington Plot in 1586. Walsingham learned that a young Catholic nobleman, Anthony Babington, was corresponding with Mary about a plan to assassinate Elizabeth and place Mary on the throne. Rather than arresting them immediately, Walsingham saw his chance to finally ensnare the Scottish queen.

He staged a brilliant sting operation. Through a double agent named Gilbert Gifford, Walsingham took control of the very channel used to smuggle letters between Mary and the conspirators—letters hidden in the waterproof casing of a beer barrel. Every single letter was secretly routed to Walsingham’s office. There, Thomas Phelippes deciphered them, Phelippes’ clerks copied them, and the originals were resealed and sent on their way.

Walsingham patiently waited, gathering intelligence, until he received what he was looking for. In a coded letter, Babington explicitly asked Mary for her approval of the “six gentlemen” assigned to dispatch Elizabeth. Mary replied, writing the fatal words that sealed her doom: she gave her assent to the assassination. Phelippes famously drew a gallows on the corner of the deciphered copy he sent to Walsingham. The trap had been sprung.

The evidence was irrefutable. Mary was tried for treason, and the damning letters, produced by Walsingham, meant the verdict was never in doubt. She was executed in February 1587, and the most significant internal threat to Elizabeth’s rule was eliminated forever.

Legacy of the Spider

Francis Walsingham was a man feared more than he was loved. Nicknamed “the Spider” for the complex webs he wove, his methods were dark and his demeanor severe. He utilized torture, blackmail, and deception as standard tools of statecraft. Yet, it is hard to argue with his results. His sleepless vigilance protected his queen and country from countless threats, helping to pave the way for the flourishing of art and culture that defined the Elizabethan age.

He died in 1590, deeply in debt after spending his personal fortune to fund his intelligence network. He was the dark knight to Elizabeth’s bright queen, the man who did the necessary dirty work so that the “Golden Age” could shine. In the shadowy history of espionage, Sir Francis Walsingham stands as a founding father—a patriot whose tireless, ruthless work secured a kingdom.