For centuries, it was a silent script. Elegant, yet impenetrable, its symbols were etched onto thousands of clay tablets unearthed from the dusty ruins of Crete and mainland Greece. This was Linear B, the writing of the powerful Mycenaean civilization—the very world of Agamemnon, Achilles, and the Trojan War, a society known mostly through the epic poems of Homer. But while Homer gave them a voice in legend, their own words were lost. Was their language Greek? Or something else entirely? The world’s leading scholars were stumped, convinced it was an unknowable, non-Greek tongue.

They were all wrong. The man who would prove it wasn’t a tenured professor or a seasoned archaeologist, but a brilliant young architect with a passion for codes—a man who had set his sights on the problem as a teenager: Michael Ventris.

The Minoan Maze

The story begins with the legendary archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. In the early 20th century, his excavations at Knossos on Crete uncovered the sprawling palace of a magnificent Bronze Age civilization he named “Minoan”, after the mythical King Minos. Amidst the ruins, he found clay tablets inscribed with three distinct scripts. The earliest was a hieroglyphic script, followed by two cursive scripts he dubbed Linear A and Linear B.

Linear A remains undeciphered to this day. Linear B, however, was found not only at Knossos but also at sites on the Greek mainland, like Pylos and Mycenae. Despite this, Evans was adamant. He believed the Minoan civilization was fundamentally non-Greek and that Linear B simply recorded his “Minoan” language. Evans was a giant in his field, and his authority was so immense that for decades, this theory became academic dogma. It sent generations of scholars down a blind alley, trying to connect Linear B to everything but Greek.

A Schoolboy’s Vow

In 1936, a 14-year-old schoolboy named Michael Ventris attended a lecture by the now 85-year-old Sir Arthur Evans at the British Museum. Ventris was captivated by the display of the strange, beautiful tablets. When Evans explained that the script remained undeciphered, something clicked. With the audacity of youth, Ventris vowed that one day, he would be the one to solve it.

Ventris was no ordinary hobbyist. He was a linguistic prodigy, fluent in multiple languages, with a mind perfectly suited for cryptography. He trained and worked as an architect, but his true passion remained the stubborn mystery of Linear B. During World War II, he put his talents to use as a codebreaker for the RAF, honing the very skills he would later turn on the ancient script. He was an outsider, unburdened by the academic dogma that had stymied the professionals.

Cracking the Code: The Grid

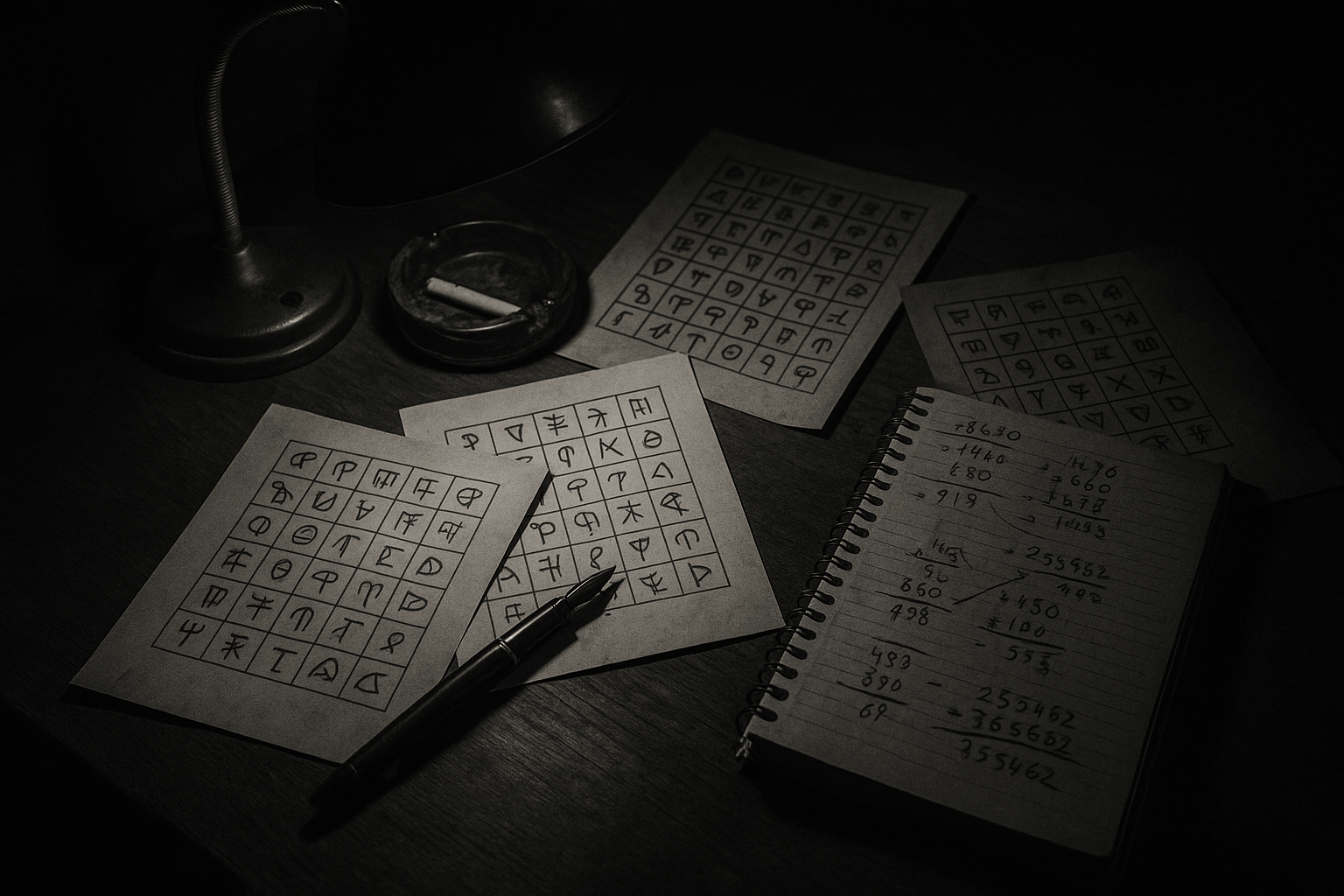

After the war, Ventris dedicated himself to the puzzle with systematic precision. He knew there was no “Rosetta Stone”—no bilingual text to provide an easy key. The code had to be broken from within. His central tool was a series of grids. Since Linear B had around 90 distinct signs, he correctly assumed it was a syllabary, where each sign represented a syllable (like pa, te, ro), not an alphabet where a sign represents a single sound (like p, t, r).

His method was a masterclass in logical deduction:

- Frequency Analysis: He cataloged which signs appeared most often, and in what positions—at the beginning, middle, or end of words.

- Identifying Vowels: He hypothesized that a few common signs that often started words were pure vowels.

- Finding Consonants: He noticed that certain signs seemed to share a consonant but have a different vowel (e.g., pa, pe, pi, po, pu). He grouped these “related” signs together in columns on his grid.

- Context from Ideograms: Crucially, many tablets featured simple pictograms—or ideograms—next to the text. A drawing of a chariot, a tripod, or a figure of a man or woman gave a clue to the subject matter of the adjacent word.

For years, Ventris diligently circulated his “Work Notes” to a small circle of scholars, sharing his progress and theories. Ironically, he too was a victim of Evans’s legacy, spending a long time trying to prove Linear B was related to Etruscan, another undeciphered ancient language. But the evidence just wouldn’t fit.

The ‘Frightful Nuisance’ of Greek

By 1952, Ventris was frustrated. His Etruscan hypothesis had led nowhere. In a moment of scientific clarity, he decided to abandon his pet theory and test the “unthinkable”—the possibility that the underlying language was, in fact, Greek. He later called it a “frightful nuisance” that complicated his theory, but he followed where the data led.

This change in perspective coincided with the publication of new tablets from Pylos. Ventris zeroed in on several words that, based on ideograms, he suspected were place names on Crete. He assigned phonetic values to the signs based on their known Greek names.

The first was a Cretan port town: A-mi-ni-so. This lined up perfectly with the known town of Amnisos.

Then another: Ko-no-so. This was unmistakably Knossos.

The pieces were falling into place. The final, electrifying proof came from a word that appeared next to an ideogram of a three-legged cauldron, or tripod. Ventris tentatively sounded out the signs on his grid:

ti-ri-po-de

The word for tripod in ancient Greek is tripodes. Then another, next to an ideogram for a boy: ko-wo. The Greek word is korwos. It was a perfect match. The grid worked. The language was Greek.

Giving a Civilization Its Voice

Stunned by his own breakthrough, Ventris reached out to John Chadwick, a young classicist at Cambridge who specialized in early Greek dialects. He cautiously presented his findings, asking if the language he had uncovered looked like a plausible version of Bronze Age Greek. Chadwick was astonished. Not only did it look plausible, but it perfectly matched academic predictions for what a pre-Homeric form of Greek should look like.

On July 1, 1952, Michael Ventris announced his decipherment on a BBC radio program. With that single broadcast, he rewrote the first chapter of European history, pushing back the origins of written Greek by over 700 years.

The contents of the tablets were not what many had hoped for. There were no epic poems, no royal histories, no lost plays. Instead, they were the meticulous, mundane records of a highly organized bureaucracy: lists of goods, inventories of weapons, records of livestock, and rosters of personnel. They were the receipts and spreadsheets of a Bronze Age palace economy.

But in their own way, they were more valuable. They gave us a direct, unfiltered glimpse into the world of the Mycenaeans. We learned the names of their gods—Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Dionysus—all present on the tablets. We learned about their social structure, their trade, and their administration. The decipherment proved that the legendary world of Homer was not just a myth, but was rooted in a real, Greek-speaking historical civilization.

Tragically, Michael Ventris would not live to see the full impact of his discovery. In 1956, just four years after his announcement, he was killed in a car accident at the age of 34. But the codebreaker’s legacy was secure. Through brilliance, persistence, and an architect’s logic, a dedicated amateur had solved a puzzle that stumped the experts, and in doing so, had given a lost world its voice back.