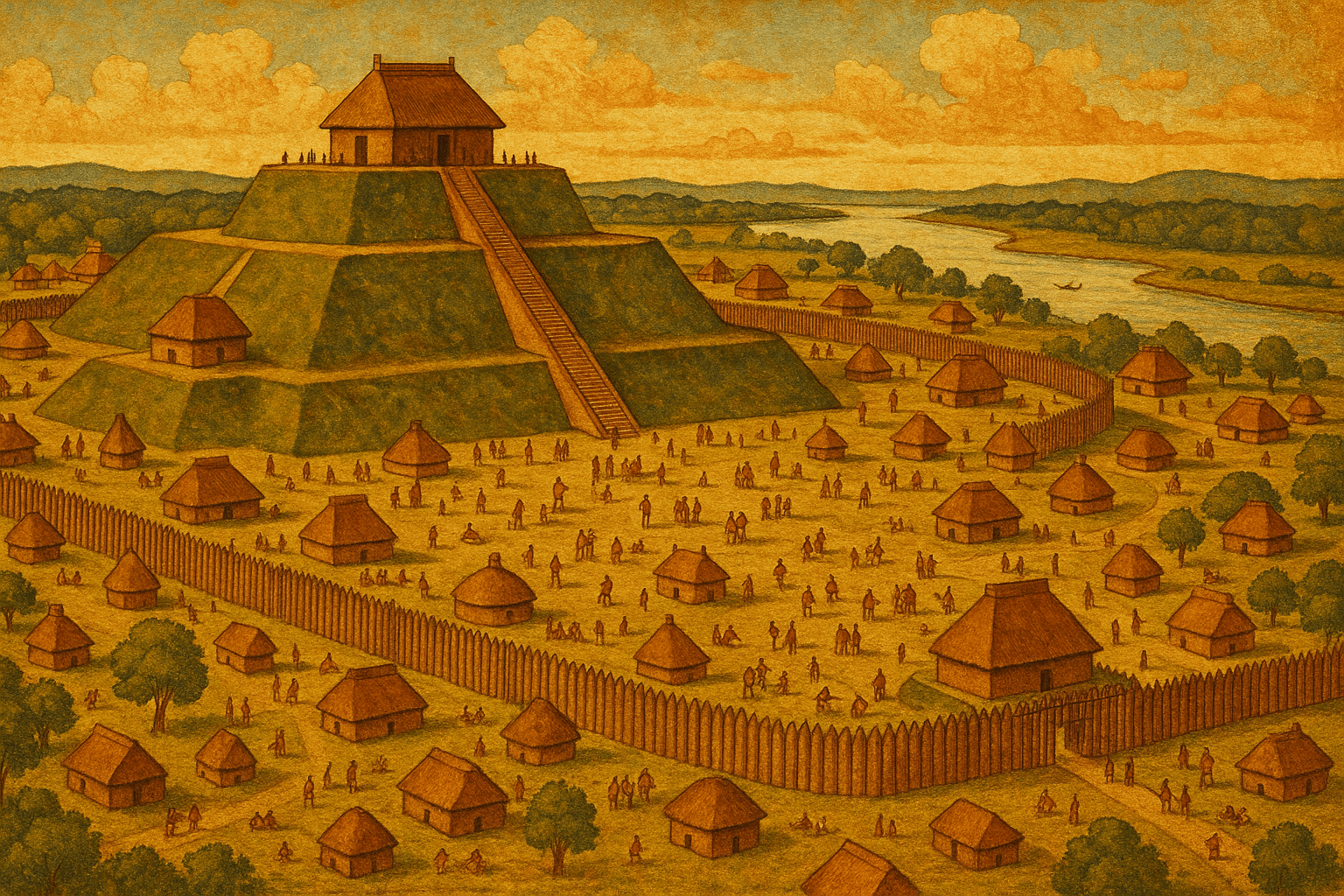

Picture a city in the heart of North America, a thousand years ago. Its central pyramid, built entirely of earth, looms over a vast plaza bustling with thousands of people. Its influence stretches for hundreds of miles, a vibrant hub of culture, religion, and trade. This wasn’t London, Paris, or Rome. This was Cahokia, the largest and most sophisticated prehistoric city north of Mexico, and its story challenges everything you thought you knew about ancient America.

The Rise of a Metropolis in the American Bottom

Nestled in a wide, fertile floodplain of the Mississippi River across from modern-day St. Louis, an area known as the “American Bottom”, Cahokia rose from humble beginnings around 700 CE. For centuries, it was a modest village. But then, around 1050 CE, something extraordinary happened—a cultural “big bang.” In a remarkably short period, the settlement exploded into a true city.

This rapid urbanization was the work of the Mississippian culture, a widespread civilization that flourished across the Midwest and Southeast. They were master farmers, cultivating the “three sisters”—corn, beans, and squash—in the rich river soil. This agricultural surplus fueled a population boom and allowed for a complex, stratified society to develop. At its peak around 1100 CE, Cahokia’s core city was home to an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 people, with tens of thousands more living in satellite farming villages. To put that in perspective, Cahokia was larger than London was at the same time.

Engineering Marvels: The Great Mounds

The most stunning legacy of Cahokia is its monumental architecture: over 120 earthen mounds. These were not simple piles of dirt; they were carefully engineered structures built by hand, with millions of baskets of earth moved over generations. The mounds served different purposes, creating a complex and symbolic urban landscape.

Monks Mound: A Monument of Earth and Power

Dominating the city’s core is the awe-inspiring Monks Mound. Standing ten stories tall (100 feet) and covering 14 acres at its base, its footprint is larger than that of the Great Pyramid of Giza. It was constructed in several stages, a colossal undertaking that required immense social organization and labor. Atop its flat summit stood a massive wooden building, likely the residence of the city’s paramount chief, a priest-ruler who governed both the political and religious lives of his people. From this vantage point, he could look down upon the city, a tangible symbol of his power and connection to the cosmos.

Woodhenge and the Grand Plaza

Just west of Monks Mound, archaeologists discovered several circles of large, evenly spaced wooden posts they nicknamed “Woodhenge.” This was not a building but a sophisticated astronomical observatory. Certain posts aligned with the sunrise on the solstices and equinoxes, allowing Cahokia’s leaders to track the seasons, manage the agricultural calendar, and schedule important festivals. It demonstrates a deep understanding of celestial mechanics, vital for a society dependent on farming.

Stretching out from the base of Monks Mound was the Grand Plaza, a 40-acre, meticulously leveled public square. This space was the heart of civic life, used for massive ceremonies, public gatherings, and ritual games. One popular game was chunkey, where a player rolled a stone disc and competitors threw spears to see who could land closest to where the disc stopped. It was far more than a sport; it was a high-stakes event with deep social and ritual significance.

A Glimpse into Cahokian Life and Death

Cahokia was a city of stark contrasts. The elite, living atop the platform mounds, enjoyed a privileged existence. Commoners lived in rectangular, single-family homes made of wood and thatch, clustered in neighborhoods throughout the city. Artisans crafted intricate pottery, arrowheads of exceptional quality, and ornaments from copper and seashells sourced from hundreds of miles away, evidence of a vast trade network extending from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.

Our most dramatic insight into Cahokia’s social structure comes from a ridge-top mound known as Mound 72. Here, archaeologists unearthed the tomb of a high-status individual, likely an early Cahokian leader. This “Birdman” was laid upon a spectacular cape made from 20,000 marine shell beads arranged in the shape of a falcon. But the burial’s grandeur is matched by its horror. Surrounding him were the remains of over 250 other people, most of them sacrificial victims. One pit contained the bodies of more than 50 young women, all aged 18 to 23, who had been executed. Another held four men, beheaded and with their hands cut off. Mound 72 is a chilling testament to the absolute power wielded by Cahokia’s rulers and the deep-seated beliefs that underpinned their society.

The Mystery of the Vanishing City

Just as its rise was meteoric, Cahokia’s decline was swift and enigmatic. Around 1250 CE, a massive defensive palisade—a two-mile-long wall of 15,000 oak and hickory logs—was erected around the city’s central precinct. It was rebuilt three times, signaling a period of intense instability and fear. By 1350 CE, the great city was all but abandoned. When Europeans arrived in the region centuries later, all they found were the silent, grass-covered mounds.

What happened? There is no single answer, but archaeologists point to a convergence of factors:

- Environmental Stress: Decades of clear-cutting forests for fuel and construction led to widespread erosion and increasingly severe flooding in the American Bottom, potentially damaging croplands.

- Resource Depletion: Supporting such a dense population likely led to the over-hunting of game and exhaustion of other local resources.

- Climate Change: The beginning of the “Little Ice Age” brought less reliable weather patterns, which could have led to crop failures and famine, undermining the chief’s authority.

- Social and Political Unrest: The rigid hierarchy, enforced by ritual and perhaps violence, may have broken down. The construction of the palisade suggests either external threats from rival groups or internal conflict between the elites and the commoners.

Cahokia was not destroyed by a single cataclysm, but likely crumbled under the weight of its own success. It stands as a powerful reminder that civilizations, no matter how great, are fragile systems. Its silent mounds are not just relics of a lost world but a testament to the ingenuity, complexity, and ultimate impermanence of human societies, challenging us to remember the incredible history that was born—and buried—in the American heartland long before it was called America.