This wasn’t a flight of fancy, but a very real and frequently used legal privilege known as privilegium clericale, or the Benefit of Clergy. For centuries, it served as a backdoor exit from the brutal justice of secular courts, offering a lifeline to those who could prove a connection, however tenuous, to the Church. It’s a story of power, faith, literacy, and one of the most curious loopholes in legal history.

The Church vs. The Crown

The origins of the Benefit of Clergy lie in the titanic 12th-century power struggle between Europe’s two great authorities: the Church and the monarchy. A central point of conflict was jurisdiction. Who had the right to punish a “man of God” who committed a crime? The king, or the Church?

King Henry II of England argued that his law was the law of the land, and it applied to everyone, including priests, monks, and deacons—collectively known as “clerks.” The Church, led by the formidable Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, vehemently disagreed. Becket insisted that clergy could only be tried and punished in ecclesiastical (Church) courts, which operated under canon law.

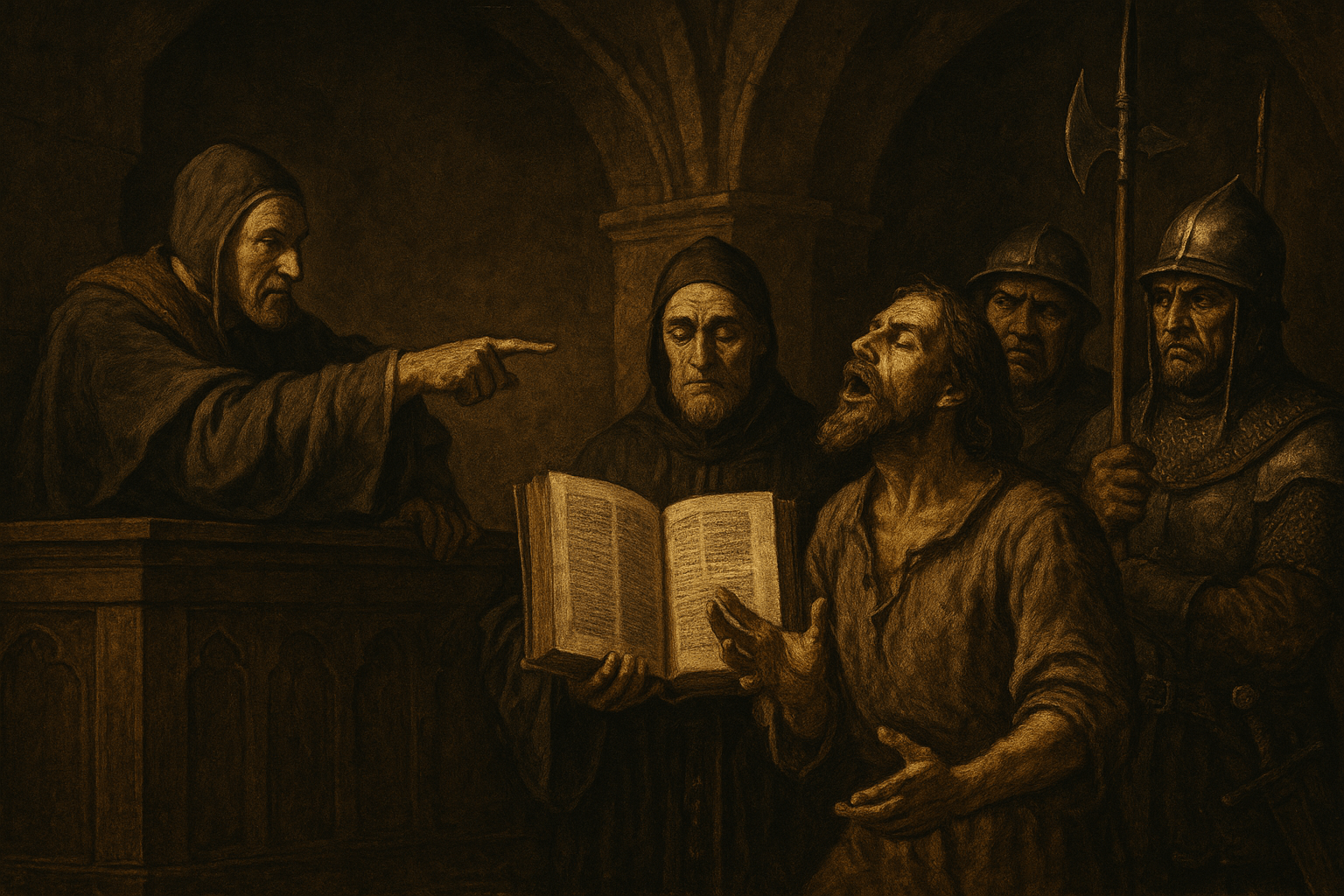

The stakes were high. Secular courts, enforcing the “King’s Peace”, were known for harsh physical punishments: hanging, beheading, mutilation, and branding. In contrast, ecclesiastical courts could not sentence a man to death. Their punishments focused on penance, fines, defrocking (stripping an individual of their clerical status), or, at worst, imprisonment in a bishop’s comfortable custody. Essentially, claiming the Benefit of Clergy was the difference between life and death.

After Becket’s infamous murder in 1170, which sent shockwaves through Christendom, the Church largely won this battle. The principle was established: secular courts could try a clerk, but if found guilty, he could claim the benefit and be handed over to the Church for a far gentler punishment.

“The Neck Verse”: A Test of Literacy

So, how did one prove they were a member of the clergy? At first, it was simple. A man’s hairstyle (the tonsure, a shaved patch on the head) and robes were usually proof enough. But as the privilege became more desirable, impostors became more common. The courts needed a more reliable test.

The solution was beautifully medieval: a literacy test. Since formal education was almost exclusively the domain of the Church, it was assumed that any man who could read was, or had been, in clerical training. The test became standardized. The accused would be given a Bible and asked to read a specific passage aloud.

The chosen passage was almost always the first verse of Psalm 51:

Miserere mei, deus, secundum magnam misericordiam tuam.

(Have mercy on me, O God, according to thy great mercy.)

This verse became famously known as the “neck verse.” If you could read it, it saved your neck from the hangman’s noose. The court official would listen and report to the judge, “Legit ut clericus” (“He reads like a clerk”), and the prisoner would be spared execution.

From Pious Privilege to Criminal Loophole

What began as a privilege for ordained priests quickly spiraled into a notorious loophole for the educated. The definition of “clerk” expanded to include not just priests and monks, but anyone in minor church orders, such as acolytes, exorcists, or even doorkeepers. More importantly, the literacy test opened the floodgates.

Savvy criminals realized that all they needed to do was learn to read—or, even more simply, memorize the single Latin sentence of the neck verse. Tutors did a brisk trade teaching illiterate rogues to recite Psalm 51:1 by rote. Some sympathetic jailers were even known to coach condemned men before their court appearance.

Judges, too, could exercise discretion. If a judge felt a particular punishment was too harsh for the crime, he might turn a deaf ear to a prisoner’s stumbling recitation and accept it as a pass. The benefit became a way for the justice system to introduce a degree of mercy into its otherwise rigid and brutal code.

One of the most famous men to use this loophole was not a common thief, but the celebrated playwright and poet Ben Jonson. In 1598, Jonson killed an actor in a duel. Found guilty of manslaughter, he faced execution. But Jonson, being a highly literate man, claimed the Benefit of Clergy. He read his neck verse, successfully evading the gallows. He did not, however, escape punishment entirely. He was branded on the base of his thumb with a “T” for Tyburn (the site of execution), marking him as a felon and preventing him from ever using the benefit again.

Closing the Loophole

By the late 15th century, the Crown had grown tired of seeing so many felons escape justice. A series of acts were passed to curtail the abuse of the Benefit of Clergy:

- It was limited to a one-time-only use for non-ordained men.

- To enforce this, the practice of branding felons on the thumb (an “M” for murder or a “T” for theft) was introduced in 1489. If a man claimed the benefit a second time, the court would check his thumb.

- Over time, the types of crimes for which the benefit could be claimed were reduced. Murder, arson, highway robbery, and other serious felonies were eventually excluded.

By the 18th century, the literacy test itself had become a legal fiction. Courts often presumed it, and the Benefit of Clergy transformed into a sort of early parole system—a sentencing tool that allowed judges to reduce a felony charge to a lesser punishment for first-time offenders.

The final curtain fell on this bizarre legal drama in 1827, when the Benefit of Clergy was formally abolished in England. The United States, having inherited English common law, had already eliminated it shortly after the Revolution, deeming it incompatible with the principle of equal justice for all. The idea that an educated man should receive a different punishment from an uneducated one was anathema to the new republic.

Today, the Benefit of Clergy is a forgotten relic. Yet it offers a fascinating glimpse into the medieval world—a world defined by the immense power of the Church, the stark divide between the literate and illiterate, and a justice system that was, in its own strange way, capable of both brutal severity and surprising mercy.