To the modern eye, chess is the ultimate game of intellect and quiet contemplation. It’s a duel of minds, played in hushed tournament halls and serene park corners. But strip away the centuries of refinement, and you’ll find something far more visceral at its core: the thunder of cavalry, the rumble of chariots, and the clash of armies on a field of battle. The 64 squares were not always a simple board; they were a microcosm of war.

The Four-Limbed Army: Chaturanga in Gupta India

Our story begins in the Gupta Empire of India around the 6th century AD. Here, a game called Chaturanga emerged, not as a pastime, but as a strategic simulation for generals and kings. The name itself is a dead giveaway, translating from Sanskrit to “four limbs” or “four divisions”, a direct reference to the classical formation of the Indian army. The board was a map, and the pieces were soldiers.

The four divisions were represented by pieces that are surprisingly familiar:

- Padàti (Infantry): A line of foot soldiers, the ancestors of our modern Pawns.

- Ashva (Cavalry): The warhorses, whose unique L-shaped movement has remained unchanged for 1,500 years, becoming our Knight.

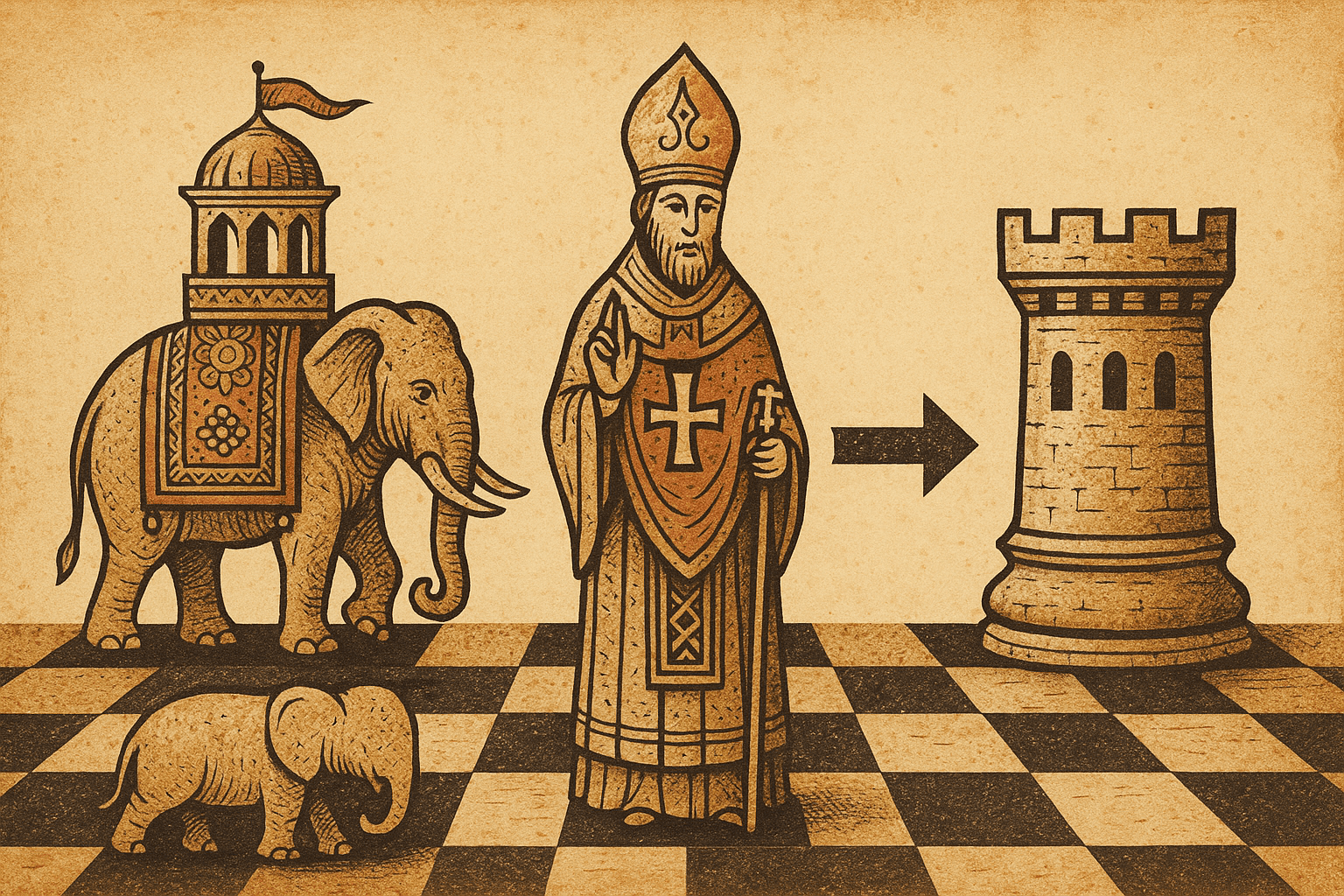

- Hasti (Elephants): The formidable war elephants that acted as living tanks in ancient battles. Their movement was different, but they occupied the position of our modern Bishops.

- Ratha (Chariots): The swift, powerful chariots that charged in straight lines, the direct forerunners of the Rook.

At the center of this force were two crucial figures: the Raja (King) and his Mantri (Counsellor or Minister). The Raja was the heart of the army; if he was captured, the game was lost. His counsellor, however, was a far cry from the powerhouse we know today. The Mantri was a weak piece, able to move only a single square diagonally. This was a reflection of reality: the counsellor advised the king but held no independent military might.

Chaturanga was a war game through and through. It taught players about tactical formations, the importance of protecting a central commander, and the coordinated use of different military units. It was Sun Tzu’s Art of War, playable on an 8×8 grid.

Persian Polish: The Rise of Shatranj

As trade and ideas flowed from India, Chaturanga journeyed west into Persia during the Sassanian Empire (around the 7th century). The Persians embraced the game, but adapted it to their own culture and language. Chaturanga became Shatranj.

The changes were subtle but significant. The pieces were renamed to fit the Persian court. The Raja became the Shah (King), and the Mantri became the Farzin (Wazir or Vizier). It is from Persian that we inherit our most famous chess terms. When a player would attack the king, they would declare, “Shah!”—literally, “The King!” The final, inescapable blow was “Shah Mat!”—”The King is finished” or “The King is helpless.” Sound familiar? It’s the direct origin of “Checkmate.”

Under the Persians and later the vast Islamic Caliphates, the rules of Shatranj were standardized into the two-player game we recognize. The game became slower, more deliberate. The Elephant (now Alfil) moved exactly two squares diagonally, jumping over the intervening square. The Farzin remained limited to its one-square diagonal move. This made Shatranj a game of patient maneuvering and long-term strategy, like a slow siege rather than a swift, open battle.

A European Makeover: From Saracens to Serfs

Shatranj entered Europe primarily through two routes: the Moorish conquest of Spain and the Byzantine trade routes into Italy. By the 11th century, it was a prized game among the European nobility. But as it spread, the game underwent a dramatic transformation, its pieces re-imagined to fit the social and military structure of medieval feudalism.

The abstract Persian forms were given new identities:

- The Shah naturally remained the King.

- The Alfil (Elephant), an animal unfamiliar to most of Europe, was a puzzle. The stylized two-humped shape of the piece was interpreted in many places as a bishop’s mitre, and so the Elephant became the Bishop.

- The warhorse was easily understood, and the Asp became the chivalric Knight.

- The Rukh (Chariot) also posed a challenge. The Persian word sounded like “Roc”, a mythical giant bird, but the piece’s shape was often a fortified tower. The castle interpretation won out, and it became the Rook.

The most intriguing change was that of the Farzin. The male counsellor was replaced by the Queen. However, for centuries, she inherited the Farzin’s weakness, moving only one diagonal square. She was a royal consort, not a ruler in her own right—a perfect reflection of the medieval European court.

The Renaissance Revolution: “Madwoman’s Chess”

For nearly 500 years, European chess remained the slow, methodical game of Shatranj. Then, around the end of the 15th century, everything changed. In Spain or Italy, a revolutionary new rule was introduced that supercharged the game: the Queen was given the combined powers of the Rook and the Bishop, instantly making her the most dominant piece on the board. The Bishop was also unleashed, now able to sweep across the entire diagonal.

This new, faster, and far more violent version of the game was called scacchi alla rabiosa in Italian—”madwoman’s chess.” Why this sudden, dramatic shift? History provides the answer. This was the age of powerful female monarchs, most notably Isabella I of Castile in Spain, a queen who wielded immense political and military power. The rise of the powerful chess queen mirrored the rise of powerful real-life queens.

This new game also reflected the changing face of warfare. The slow, grinding sieges of the medieval era were giving way to more dynamic battles, influenced by new technologies and tactics. The chess game sped up accordingly, becoming a game of swift, brutal attacks and sudden, decisive checkmates.

Even the humble Pawn’s promotion took on new meaning. A foot soldier reaching the end of the board could now become a Queen, a powerful metaphor for social mobility in a Renaissance world where the old, rigid feudal orders were beginning to crack.

The Battlefield in the Box

From an Indian battlefield simulator to a Persian courtly pastime, from a reflection of European feudalism to a symbol of Renaissance dynamism, the evolution of chess is a history of the world in miniature. The game on your table is a living artifact, its rules and pieces shaped by empires, armies, and social revolutions.

So the next time you advance a pawn or unleash your queen, remember the long journey those pieces have taken. You aren’t just playing a game; you’re re-enacting a 1,500-year-old story of war, power, and history.