The Seeds of Rebellion: Life in the Salt Marshes

The Abbasid Caliphate, ruling from its magnificent capital of Baghdad (and later Samarra), was a global center of culture, science, and commerce. But its vast wealth was built on foundations that included conquest and exploitation. In the sweltering, humid salt marshes of southern Iraq, near the thriving port city of Basra, a massive and cruel agricultural experiment was underway.

Wealthy proprietors had undertaken a colossal land reclamation project. Their goal was to transform the saline, unproductive wetlands into fertile farmland for crops like sugarcane. The labor for this back-breaking work was supplied by a huge population of enslaved people, drawn primarily from the coast of East Africa, an area the Arabs referred to as the “Land of the Zanj.”

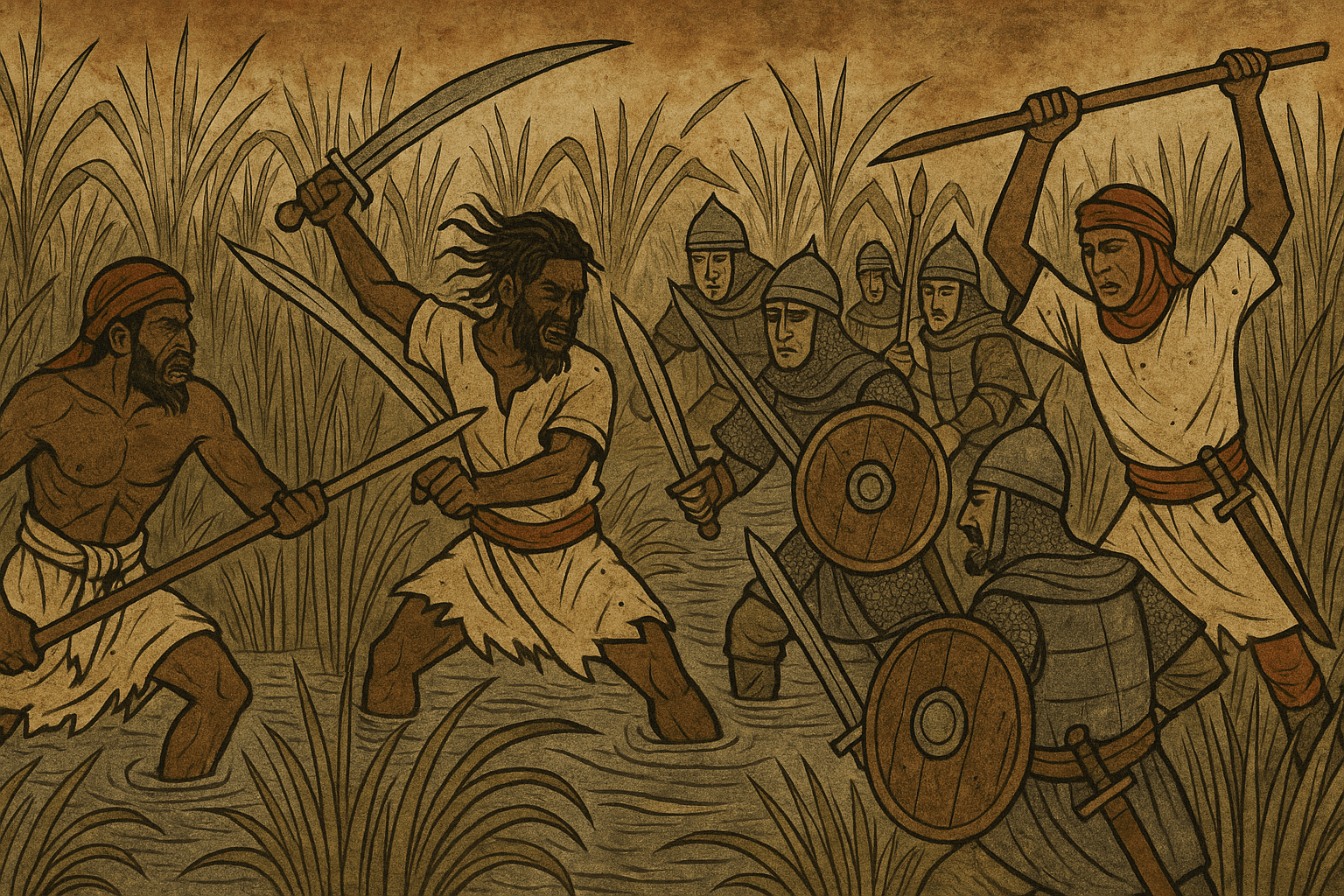

The conditions were horrific. Organized in large gangs, the Zanj laborers spent their days scraping the salty topsoil in the blistering sun, digging canals, and enduring constant exposure to the elements. They were given meager rations, lived in squalid camps, and were subject to the whims of brutal overseers. The sheer concentration of thousands of desperate people in one place, all sharing a common suffering, created a volatile powder keg waiting for a spark.

The Rise of a Charismatic Leader: Ali ibn Muhammad

The spark arrived in 869 CE in the form of a man named Ali ibn Muhammad. A mysterious figure of Persian or Arab origin, he was not one of the Zanj, but he saw their plight as his opportunity. Ali was a brilliant political operator with a powerful message. He claimed descent from Ali ibn Abi Talib, the Prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law, a claim that lent him immense religious legitimacy in the Shia-oriented region of southern Iraq.

He arrived in the marshes and began to preach a radical doctrine of liberation. He adopted an ideology similar to Kharijism, an egalitarian sect of Islam which held that any pious Muslim, regardless of race or social standing, could lead the community. To the enslaved Zanj, who were often looked down upon as heathens or inferior Muslims, this was a revolutionary idea. Ali ibn Muhammad declared himself the “Mahdi” (the rightly guided one) and promised the enslaved not just freedom, but riches, power, and vengeance against their masters.

His message resonated deeply. Thousands flocked to his banner, and the rebellion exploded with a ferocity that caught the Abbasid authorities completely off guard.

Forging a State from the Swamps

The early years of the rebellion were a stunning success for the Zanj. They used their intimate knowledge of the treacherous marshlands to their advantage, conducting swift guerrilla raids and ambushing Abbasid forces who were unused to the difficult terrain. The canals that had been their prison became their highways, allowing them to move quickly and evade capture.

But this was far more than a simple uprising. Under the leadership of Ali ibn Muhammad, the Zanj began building a functioning state. They established a capital city, al-Mukhtara (“The Chosen City”), deep within the marshes, protected by a network of canals and fortifications. From this base, they organized a formidable army and navy. The new Zanj state had its own bureaucracy, treasury, and even minted its own coins. It was a defiant declaration of sovereignty.

In a dark turn of irony, the newly freed Zanj became enslavers themselves. Captives taken in their raids, including their former masters, were put to work. This complex reality complicates any simple narrative of pure liberation, highlighting the brutalizing nature of the world they inhabited.

A 14-Year Challenge to an Empire

The Abbasid Caliphate initially underestimated the rebellion. The central government in Samarra was consumed by its own internal turmoil—a period known as the “Anarchy at Samarra”—with powerful Turkic generals vying for control and assassinating caliphs. This disarray allowed the Zanj to consolidate their power and expand their territory.

In 871 CE, the rebels achieved their most shocking victory: the capture and sack of Basra, one of the empire’s most important commercial hubs. The fall of the city sent a shockwave through the Caliphate. Accounts from the historian al-Tabari describe a merciless slaughter, with much of the city put to the torch. For over a decade, the Zanj terrorized southern Iraq, capturing other major towns like Wasit and threatening the routes to Baghdad itself.

The conflict was astoundingly bloody. Historians estimate the death toll from the 14-year war to be anywhere from 500,000 to over 2 million people, though these figures are likely exaggerated. What is certain is that the war was one of the most destructive episodes in the region’s history.

The Fall of al-Mukhtara and the End of the Rebellion

By the late 870s, the Abbasid Caliphate had finally stabilized under the firm hand of the Caliph’s brother and regent, al-Muwaffaq. Recognizing the existential threat posed by the Zanj, he marshaled the full military and economic might of the empire to crush them once and for all.

Al-Muwaffaq was a methodical and patient general. He had a large fleet built to blockade the waterways and sever the Zanj supply lines. He offered amnesty and rewards to any rebels who would desert, slowly eroding Ali ibn Muhammad’s support. His army painstakingly advanced into the marshes, building causeways and besieging Zanj strongholds one by one.

The final campaign focused on the capital, al-Mukhtara. The siege began in 881 CE and was a long, grinding affair. After two years of relentless pressure, the Abbasid forces finally breached the city’s defenses in August 883 CE. In the final battle, Ali ibn Muhammad was killed. His head was cut off and sent to Baghdad as proof of victory, and the rebellion was brutally extinguished.

The Legacy of the Zanj

The Zanj Rebellion left an indelible mark on the Abbasid world. The agricultural heartland of southern Iraq was utterly devastated and never fully returned to its former prosperity. The demographic and economic cost was immense.

Most significantly, the rebellion fundamentally changed the nature of slavery in the region. The sheer terror inspired by the uprising made landowners abandon the practice of large-scale, plantation-style gang slavery. While slavery itself continued in the Islamic world for centuries, never again would such a massive, concentrated population of a single ethnic group be used for this kind of labor in the heart of the empire. The Zanj had, through their violent struggle, ensured they would have no successors.

Though ultimately crushed, the Zanj Rebellion stands as a powerful testament to the agency of the enslaved and their unquenchable desire for freedom. For fourteen years, they not only fought one of the world’s great powers to a standstill but built their own functioning state, proving that even in the most hopeless of circumstances, the oppressed can rise to challenge the very foundations of their world.