The story of the Xiongnu is a gripping saga of nomadic power, sophisticated politics, and a clash of civilizations that defined an age and left a permanent mark on the map of China—the Great Wall.

Who Were the Xiongnu?

The exact origins of the Xiongnu are shrouded in mystery, a puzzle that still fascinates historians. Chinese records from before the Han Dynasty speak of various northern “barbarian” tribes, often grouped together as the “Hu.” It was from these disparate groups that the Xiongnu confederation emerged. They were not a single ethnic group but a multi-lingual, multi-ethnic alliance of pastoral nomadic tribes who roamed the arid grasslands of modern-day Mongolia and Siberia.

Their lives were dictated by the rhythm of the seasons and the needs of their vast herds of horses, sheep, and cattle. Living in felt-covered yurts (known as gers), they could pack up their entire existence and move across the steppe in search of fresh pasture. This constant mobility was not just a way of life; it was the source of their military might.

Forging an Empire: The Rise of Modu Chanyu

For a long time, the Xiongnu tribes were a disunited collection of clans, a nuisance to China’s northern border but not an existential threat. That all changed with the rise of one of history’s most ruthless and brilliant leaders: Modu Chanyu (r. 209-174 BCE).

The story of Modu’s ascent, recorded by the Han historian Sima Qian, is the stuff of legend. Modu’s father, the Chanyu (the supreme ruler) Touman, favored a younger son and planned to have Modu killed. Sent as a hostage to a rival tribe, the Yuezhi, Modu’s father then launched a surprise attack on them, expecting them to execute his son. But Modu, a skilled warrior, stole a prize horse and escaped back to his people.

Impressed by his daring, his father gave him command of 10,000 horsemen. Modu then developed a terrifying tool of absolute loyalty: the “singing arrow”, an arrowhead that whistled as it flew. He gave his men a chilling command: “Shoot wherever my singing arrow flies. Anyone who fails to shoot will be executed.”

He tested them relentlessly.

- First, he shot his own favorite horse. Any man who hesitated was immediately beheaded.

- Next, he shot his favorite wife. Again, he executed those who failed to follow his lead.

- Finally, during a hunting trip with his father, Modu aimed his singing arrow at the Chanyu Touman. Every single one of his men fired, and the old Chanyu fell, riddled with arrows.

After eliminating his rivals, Modu Chanyu declared himself the new supreme ruler in 209 BCE. He swiftly conquered neighboring tribes, forging the fractious nomads into a unified and terrifyingly effective political and military machine—the Xiongnu Empire.

The Structure of a Steppe Empire

Under Modu, the Xiongnu established a sophisticated political structure that would become a blueprint for later steppe empires. At the top was the Chanyu, who ruled from the center. The empire was divided into two main wings:

- The Wise King of the Left (East): Typically the heir apparent, ruling over the eastern part of the empire.

- The Wise King of the Right (West): Ruling over the western territories.

Beneath them was a hierarchy of lesser chiefs, each commanding groups of 10,000, 1,000, 100, and 10 men. This decimal system allowed for incredibly rapid mobilization of troops across the vast steppe. The society, while patriarchal, granted women considerable agency in managing the household economy and could wield influence in court politics, especially during successions.

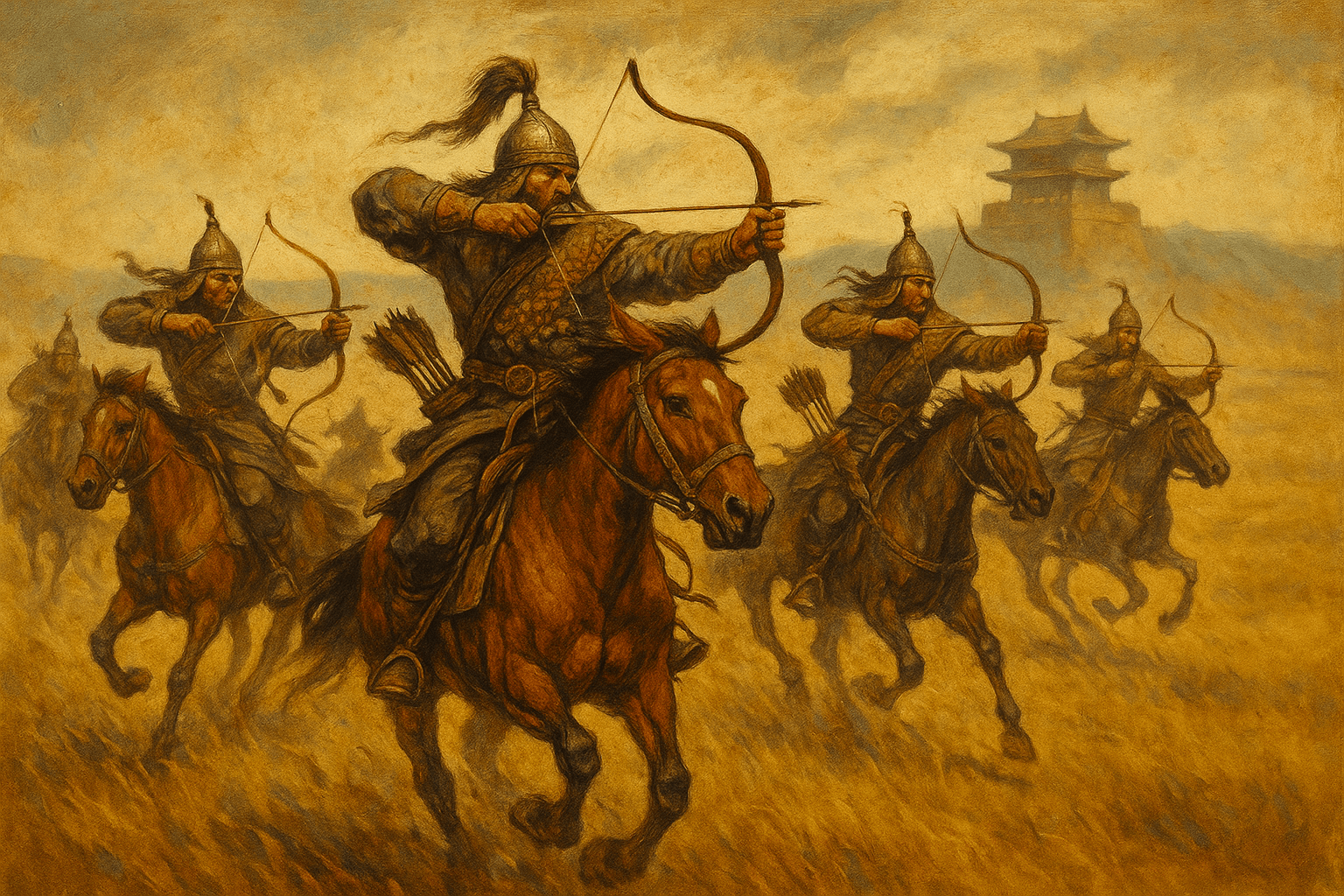

The Xiongnu War Machine

The Xiongnu military was a direct extension of their nomadic lifestyle. Every able-bodied Xiongnu man was a warrior. Taught to ride horses and shoot a bow from childhood, they were the original horse archers. Their military advantage lay in several key areas:

- Unmatched Mobility: Their all-cavalry armies could cover vast distances, strike deep into enemy territory, and vanish before a slower, infantry-based army could respond.

- The Composite Bow: Wielded from horseback, this powerful bow could punch through armor and outrange the weapons of their enemies.

- Guerilla Tactics: The Xiongnu perfected hit-and-run warfare. Their most famous tactic was the feigned retreat, where they would pretend to flee, lure an enemy into a disorganized pursuit, and then turn to annihilate them in a prepared ambush.

These tactics made them the terror of the Han Dynasty’s northern frontier.

A Rivalry for the Ages: Xiongnu and the Han Dynasty

The newly unified Xiongnu under Modu coincided with the founding of the Han Dynasty in China (206 BCE). The clash was immediate and spectacular. In 200 BCE, the founding Han Emperor Gaozu, brimming with confidence, personally led an army to confront Modu. He was promptly lured into a trap and besieged at the Battle of Baideng for seven days. Humiliated, the emperor only managed to escape through a clever ruse.

This defeat led to the creation of the heqin policy, or “peace and kinship.” For nearly 70 years, the Han pursued a policy of appeasement. It involved:

- Sending Han noblewomen to marry the Xiongnu Chanyus.

- Delivering massive annual payments of tribute, including silk, grain, and wine.

- Recognizing the Xiongnu as a theoretically equal state.

This policy was a national humiliation for the Han, but it bought them precious decades of relative peace to consolidate their power. It all changed with the ascension of the “Martial Emperor”, Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141-87 BCE). He saw the heqin policy as a sign of weakness and launched a series of massive military campaigns to destroy the Xiongnu. The Han-Xiongnu Wars were among the largest and longest conflicts of the ancient world. Emperor Wu professionalized the Han army, developing a huge cavalry force to fight the Xiongnu on their own terms. These wars, led by legendary generals like Wei Qing and Huo Qubing, pushed the Xiongnu far back into the steppe, but at a staggering cost that nearly bankrupted the Han treasury.

It was during this epic struggle that the Great Wall of China as we often imagine it took shape. The Han connected, fortified, and extended earlier walls specifically as a defense-in-depth system against Xiongnu raids. The Wall was not an impenetrable barrier but a military line with garrisons, watchtowers for signaling, and a road to quickly move troops along the frontier.

Decline and Enduring Legacy

The relentless pressure from the Han wars, combined with internal succession struggles and possibly climate-related hardships, eventually fractured the Xiongnu confederation. By the middle of the 1st century BCE, it had split into two rival groups: the Southern Xiongnu, who submitted to the Han as vassals, and the Northern Xiongnu, who remained defiant but were eventually driven further and further west.

The legacy of the Xiongnu is immense. They created the governing model for all subsequent steppe empires, from the Göktürks to the Mongols. More tantalizingly, many historians believe that the remnants of the Northern Xiongnu who migrated west eventually re-emerged in Europe two centuries later as the Huns, led by Attila. While the “Xiongnu-Hun” connection is still debated, the timeline and cultural similarities are compelling.

The Xiongnu were far more than just “barbarians” at the gate. They were a sophisticated and resilient people who built an empire that stood toe-to-toe with one of the most powerful dynasties on Earth. They were the rival that tested the Han, shaped its foreign policy, and spurred the construction of one of the world’s greatest wonders, proving that from the vast and seemingly empty steppe could arise a power to challenge civilization itself.