Look around you. Take a moment to catalogue the colors in your immediate vicinity. You’ll likely see blacks, whites, browns, and greens. If you’re inside, you might see the vibrant reds and yellows of artificial objects. But how much blue do you see, especially in a natural landscape? Aside from the vast, untouchable canvases of the sky and the sea, blue is a surprisingly shy color on our planet. There are no blue animals in the way there are green ones, and blue flowers are the result of complex botanical tricks rather than a simple pigment.

This natural rarity is reflected in our own history. For millennia, our ancestors lived in a world largely devoid of blue. It was one of the last colors to be named in almost every ancient language, and its story is one of alchemy, obsession, global trade, and human ingenuity. It’s the story of a color that had to be invented before it could truly be seen.

The Color That Wasn’t There

One of the most fascinating clues to blue’s elusive nature comes from ancient texts. The 19th-century scholar William Gladstone (who later became Prime Minister of Great Britain) was the first to notice something odd while studying Homer’s The Odyssey. The epic poem is filled with rich descriptions of glistening armor, dark sheep, and green honey. Yet, Homer describes the ocean not as blue, but as a “wine-dark sea.” He never uses a word for the color blue.

Linguists who followed up on this discovery found the same pattern across the globe. Ancient Greek, Chinese, Japanese, and Hebrew texts had no specific word for blue. The color was often lumped in with green or sometimes black. The reason is simple: without access to the color, you don’t need a word for it. Unlike red ochre from the earth, black from charcoal, or white from chalk—pigments available since the Stone Age—there was no easy, stable source for blue.

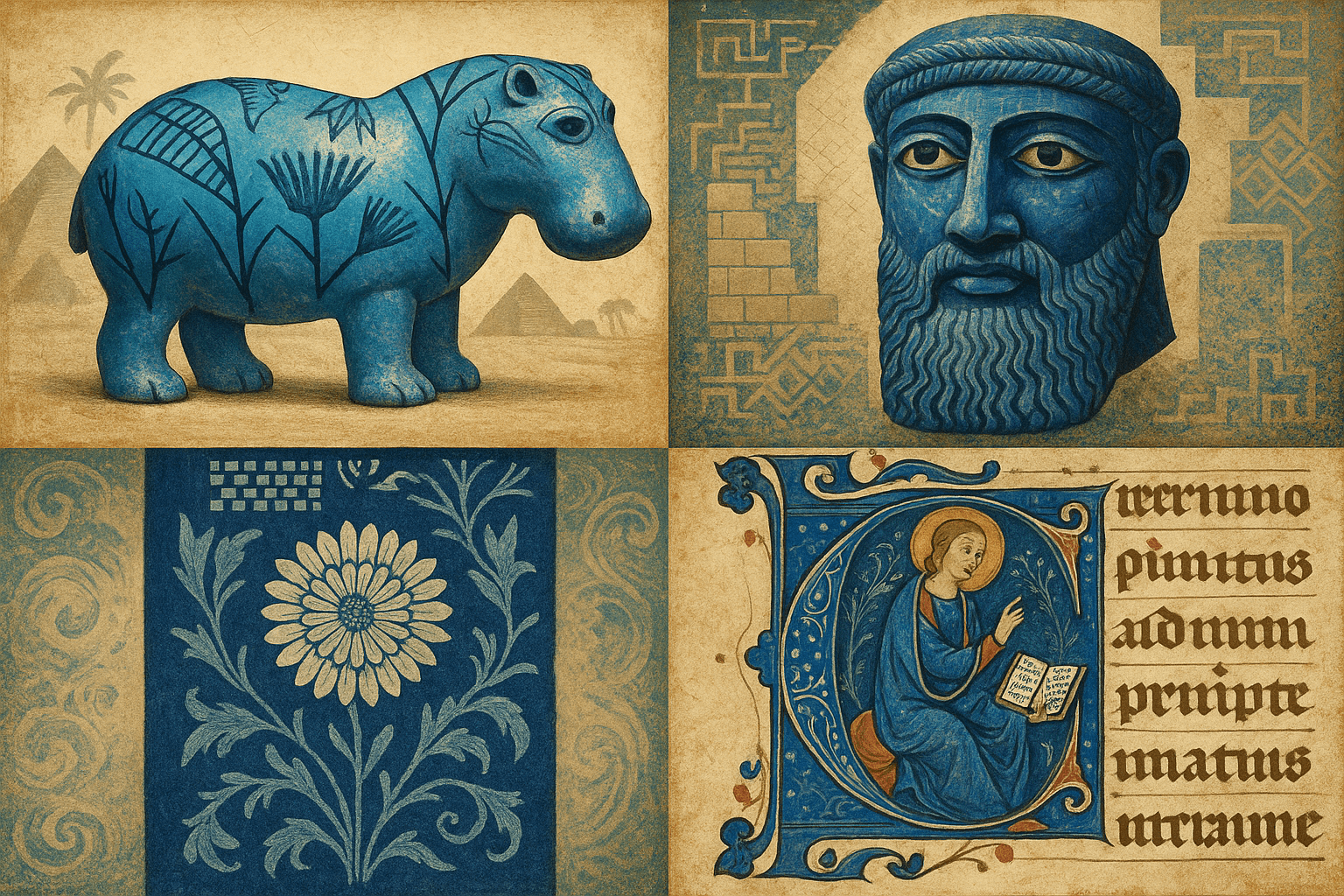

Egypt’s Revolutionary Blue

The first civilization to truly conquer blue was, unsurprisingly, the ancient Egyptians. Around 2,600 BCE, they developed what is now considered the world’s first synthetic pigment: Egyptian Blue. This was not a lucky accident but a feat of high-tech chemistry that wouldn’t be replicated for thousands of years.

The recipe was a closely guarded secret, a form of ancient alchemy. Egyptian artisans would:

- Grind silica (sand) with lime (from limestone).

- Add a copper-containing mineral, such as malachite or azurite.

- Heat this mixture in a furnace to a precise, searing temperature between 800 and 900°C (1470-1650°F).

If the temperature was too low, the reaction failed. If it was too high, it produced a useless, glassy black mess. But when done correctly, the result was a vibrant, stable blue crystal frit that could be ground into a permanent pigment. For the first time, a civilization could mass-produce blue. This brilliant color adorned the tombs of pharaohs, the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun, paintings, and everyday pottery. The Romans later inherited the formula, calling it caeruleum, but with the fall of the Roman Empire, the secret to making Egyptian Blue was lost for nearly 1,500 years.

The Gemstone of the Heavens: Lapis Lazuli

While the Egyptians were busy inventing blue, another, even more precious version of the color was being painstakingly mined halfway across the world. In a single, remote set of mountains in modern-day Afghanistan, miners dug for lapis lazuli, a deep blue semi-precious stone flecked with golden pyrite.

This was the only known source of lapis in the ancient world. The journey of these stones from the treacherous Sar-i-Sang mines to the markets of Mesopotamia and Egypt was an epic of early global trade. Lapis lazuli was more valuable than gold; its presence in an artifact was the ultimate symbol of wealth and divine connection. The iconic death mask of Tutankhamun features eyebrows and eyeliner made from pure lapis lazuli.

Thousands of years later, during the Renaissance, this same stone found its most revered purpose. European artists learned to grind lapis lazuli into the most exquisite and expensive pigment of all time: Ultramarine. The name itself means “from beyond the sea,” a direct reference to its exotic, distant origins. Due to its astronomical cost, artists reserved Ultramarine for only the most sacred subjects. In Renaissance painting, the robes of the Virgin Mary are almost always painted in brilliant Ultramarine, a color that symbolized her purity, humility, and status as the Queen of Heaven.

The People’s Blue: Woad and Indigo

While Egyptian Blue and Ultramarine were pigments for the elite, the desire for blue was just as strong among the common people, especially for textiles. For centuries, Europe’s only source of blue dye came from the humble woad plant, Isatis tinctoria. The process of extracting the dye was smelly and labor-intensive, involving fermenting the leaves in vats of urine. Roman accounts from Julius Caesar famously claimed that the Celtic warriors of Britain painted their bodies with woad to appear more terrifying in battle.

The European woad economy thrived for centuries, creating powerful guilds and enriching regions like Toulouse, France. But its dominance was eventually shattered by a foreign rival: Indigo. Harvested from the Indigofera tinctoria plant in India, indigo produced a richer, more colorfast, and more concentrated blue. When Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama opened up a direct sea route to India in the late 15th century, high-quality indigo began to flood European markets.

The woad industry fought back desperately, launching protectionist campaigns and even branding the foreign dye as “The Devil’s Dye.” But they couldn’t compete. By the 18th century, indigo had triumphed, becoming a cornerstone of colonial trade and eventually giving the world its most iconic blue garment: blue jeans.

From a word that didn’t exist to a color worth more than gold, the history of blue is a microcosm of human history itself. It is a story of discovery, of science breaking new ground, of global trade connecting distant peoples, and of art reaching for the divine. The next time you pull on a pair of blue jeans or admire a deep blue sky, remember the thousands of years of human struggle and ingenuity it took just to be able to see it.