A Mysterious Origin: Where Did the Etruscans Come From?

One of the most enduring questions about the Etruscans is where they came from. Even the ancient writers couldn’t agree. The Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BCE, claimed they were migrants from Lydia in Anatolia (modern Turkey), who fled famine to find a new home in Italy. Conversely, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a Greek historian living in Rome centuries later, argued passionately that the Etruscans were indigenous, having always lived in Italy.

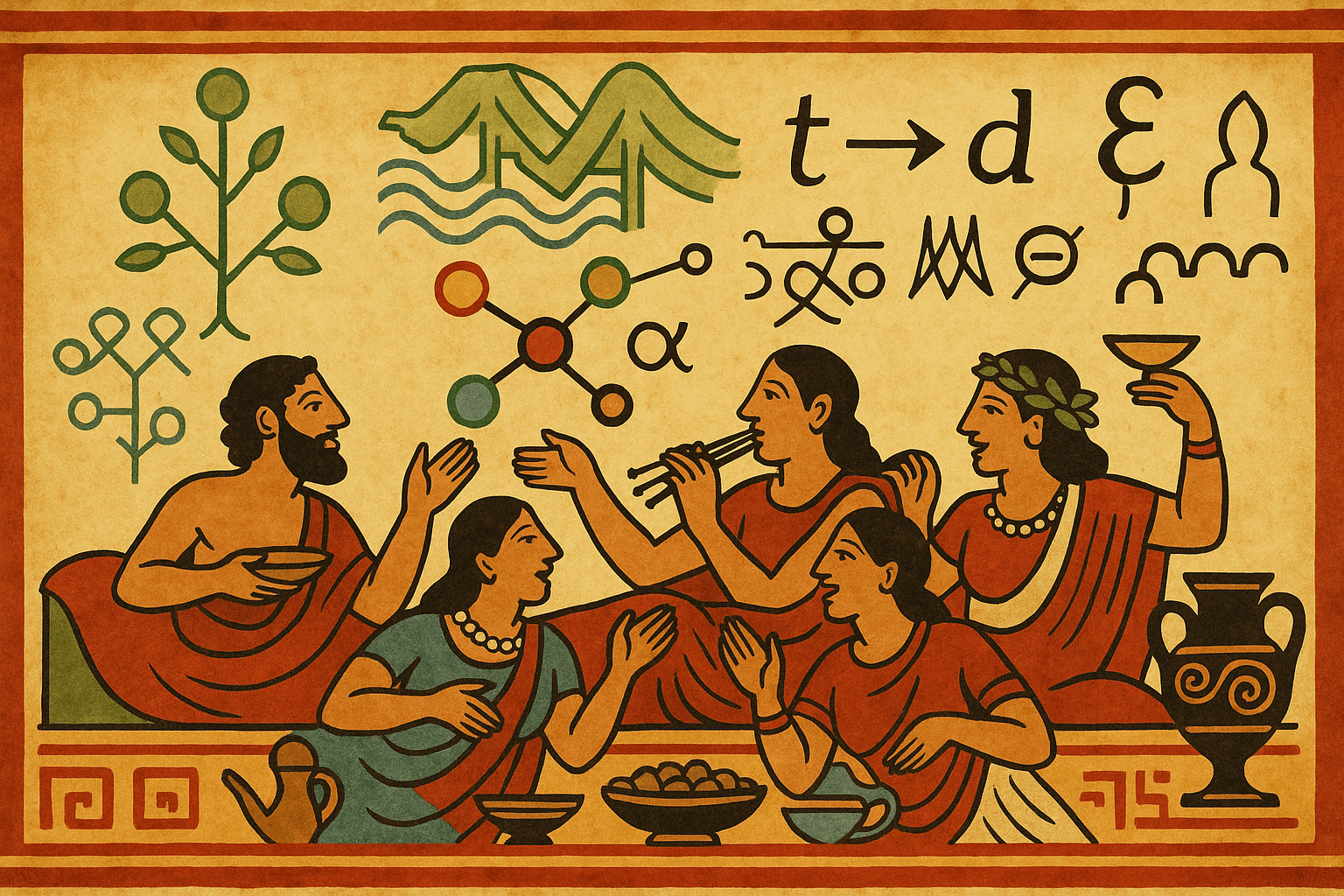

Modern science has only deepened the intrigue. Cultural evidence, such as their alphabet (adapted from Greek) and artistic styles, certainly shows strong connections to the Eastern Mediterranean. Yet, recent genetic studies on Etruscan remains have largely pointed to a deep, local genetic root, supporting the indigenous theory. The most likely scenario is a fascinating blend of both: a native Italic people whose culture was profoundly transformed through trade, contact, and migration from the east. This fusion created something entirely new and distinctly Etruscan.

A Language Unlike Any Other

Perhaps the greatest mystery the Etruscans left behind is their language. While we can read their script—they borrowed an alphabet from Greek colonists—we can’t understand most of what it says. This is because Etruscan is a “language isolate.” It isn’t related to the Indo-European family of languages, which includes Latin, Greek, Sanskrit, and most modern European languages. Trying to decipher it using Latin or Greek as a guide is fruitless.

Imagine finding a book, being able to sound out every word perfectly, but having no dictionary to tell you what the words mean. That’s the challenge for Etruscologists. Our limited understanding comes from a few key sources:

- Funerary Inscriptions: The vast majority of the 13,000 known Etruscan texts are short, repetitive epitaphs found in tombs. They give us names, parentage, and age at death, but little else.

- The Pyrgi Tablets: A groundbreaking discovery from 1964, these three golden plaques contain a short dedication to a goddess written in both Etruscan and Phoenician. This bilingual text was a mini-Rosetta Stone, giving us a crucial but small window into the language.

- The Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis: The longest known Etruscan text is, bizarrely, preserved on the linen wrappings of an Egyptian mummy. It appears to be a ritual calendar, detailing religious ceremonies, but much of its vocabulary remains obscure.

Because of this linguistic barrier, the Etruscans can’t tell us their history in their own words. We are forced to see them primarily through their art and the often-biased accounts of their Greek and Roman rivals.

Life, Death, and the Afterlife: The Vibrant World of Etruscan Tombs

Fortunately, the Etruscans spoke volumes through their art, most of which survives in their elaborate tombs. The Etruscans built vast necropolises, or “cities of the dead”, like those at Tarquinia and Cerveteri. These were not just graveyards; they were sprawling, organized communities with streets, squares, and tomb-houses carved from the soft volcanic rock to mimic the homes of the living.

Inside, the walls explode with color and life. Unlike the solemn and martial art of other cultures, Etruscan tomb frescoes depict a world of joy and celebration. In the Tomb of the Leopards at Tarquinia, elegantly dressed men and women recline on couches, attended by servants, while musicians play and dancers move to an unheard rhythm. The Tomb of the Triclinium shows a similar scene of an aristocratic banquet, a snapshot of life’s pleasures intended to last for eternity.

Their sarcophagi tell a similar story. The world-famous Sarcophagus of the Spouses, a terracotta masterpiece, shows a husband and wife reclining together on a banqueting couch. They are not stiff, divine figures, but a loving, animated couple. She may be pouring perfume into his hand; he has his arm around her shoulder. They are equals, partners in life and in death. This art tells us that the Etruscans viewed the afterlife not as a place of judgment, but as a continuation of life’s greatest joys.

The Etruscan Woman: An Anomaly in the Ancient World

The image of men and women dining together, as seen in Etruscan art, was shocking to their contemporaries. In Greece, respectable women were sequestered at home and would never attend a symposium with men. Roman women had more freedom but were still legally and socially subordinate. The Etruscans were different.

Etruscan women enjoyed a remarkably high status. They:

- Attended public banquets, sporting events, and performances with their husbands.

- Were often literate, unlike the majority of women in the ancient world.

- Retained their own names and were celebrated in family lineages. Funerary inscriptions often identify the deceased by referencing both the father’s and mother’s names.

Greek and Roman writers, viewing this through their own patriarchal lens, often misinterpreted this freedom as licentiousness. In reality, it points to a society where women were more integrated, visible, and respected partners in public and private life—a social structure far ahead of its time.

The Shadow of Rome: The Decline of Etruria

So what happened to this dynamic and sophisticated civilization? The answer lies in one word: Rome.

Etruria was never a single, unified empire. It was a loose confederation of twelve powerful city-states (the Dodecapolis), which often competed with one another. This internal division would prove to be their fatal weakness. Meanwhile, a small city-state on the Tiber river, once ruled by Etruscan kings (the Tarquins), was growing in ambition and military might.

After the Romans overthrew their Etruscan monarchy in 509 BCE, a long, slow conflict began. The fall of the powerful Etruscan city of Veii in 396 BCE, after a legendary ten-year siege, was the beginning of the end. Over the next two centuries, Rome systematically conquered, allied with, or absorbed the remaining Etruscan cities one by one.

The end was not just military but cultural. As Etruscans were integrated into the Roman system and granted Roman citizenship, they began to adopt the Latin language and Roman customs. By the 1st century BCE, the Etruscan language fell silent, and their unique identity had dissolved into the fabric of the burgeoning Roman Republic. They weren’t just erased; they were assimilated. Many of their traditions, from gladiatorial combat to religious rituals and architectural innovations like the arch, were adopted and adapted by Rome, becoming a foundational, if often unacknowledged, part of its own incredible legacy.