When we picture a lighthouse keeper from the age of sail, the image that often comes to mind is a grizzled man with a pipe, weathered by sea salt and solitude, standing sentinel against a raging storm. While many men did live this life, this popular image obscures a fascinating and vital truth: for over a century, hundreds of women officially and unofficially ran the lighthouses that guarded America’s coasts. They were keepers of the light, paragons of resilience, and their stories of courage have been largely relegated to the footnotes of maritime history.

From Assistant to Keeper: The Path to the Tower

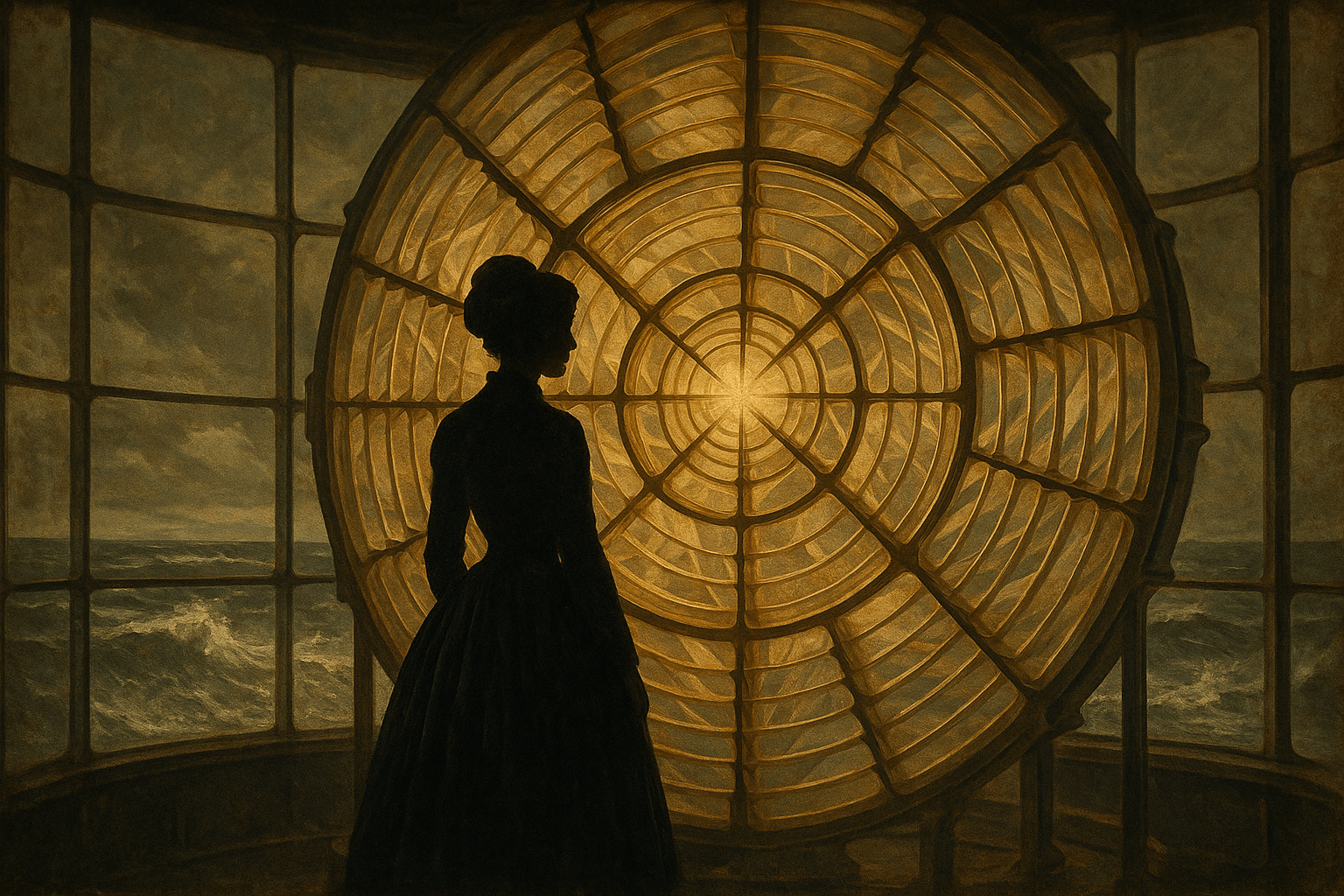

How did a woman in the 19th or early 20th century come to hold one of the most demanding and isolated government posts available? The most common path was through family. Women often served for years as unpaid “assistant keepers” to their husbands, fathers, or brothers. They learned every aspect of the grueling job: how to trim the wicks, haul gallons of whale oil or kerosene up treacherous spiral staircases, and meticulously polish the delicate, priceless Fresnel lenses that cast the life-saving beams miles out to sea.

When the official male keeper died or became incapacitated, these women were the most qualified candidates to take over. Faced with the choice of appointing an experienced woman on-site or a “green” man from the mainland, the U.S. Lighthouse Service—often pragmatically—chose the former. For many women, it was a choice born of necessity. A widow with children might be left destitute without the keeper’s position, which provided not only a salary but also a home—albeit a remote and challenging one.

Heroines of the Coast: Stories of Incredible Fortitude

The service records of these female keepers are filled with accounts of astonishing bravery. They weren’t just maintaining a light; they were performing rescues, weathering hurricanes, and displaying a grit that rivaled any of their male counterparts.

Ida Lewis: “The Bravest Woman in America”

Perhaps the most famous female keeper, Ida Lewis of the Lime Rock Lighthouse in Newport, Rhode Island, was a national sensation. Taking over for her ailing father, she became the official keeper in 1879. She was renowned for her physical strength and expert oarsmanship, often rowing her heavy lifeboat into treacherous waters to save those in peril. Her official record credits her with saving 18 lives, though the true number is believed to be closer to 25. President Ulysses S. Grant visited her, and her fame was so great that her lighthouse became a major tourist attraction. Yet, she never shirked her duty, once remarking, “The light is my child, and I know when it needs me, even if I sleep.”

Abbie Burgess: The Teenager and the Storm

The story of Abbie Burgess is one of sheer adolescent tenacity. In 1856, her father, the keeper of the Matinicus Rock Light Station—a desolate granite speck 25 miles off the coast of Maine—left to fetch supplies. He was stranded on the mainland for nearly a month by a ferocious nor’easter. A teenage Abbie was left to care for her invalid mother and younger sisters. For weeks, as storm waves swept completely over the island, threatening to wash their small dwelling away, Abbie single-handedly kept the two lights burning. She rationed their food down to one egg and a cup of cornmeal a day and even managed to save their chickens by luring them into the lighthouse tower. Her unwavering dedication ensured that not a single ship was wrecked on the dangerous shoals during that time.

Kate Walker: The “Tidy” Keeper of New York Harbor

When her husband, the keeper of the Robbins Reef Lighthouse in New York Harbor, died of pneumonia in 1890, Kate Walker was determined to take his place. Officials were skeptical, claiming the 5-foot-tall, 100-pound woman was too small for the job. She proved them wrong, serving as the official keeper for over 30 years. From her lonely “tin can on a platter”, she rowed her own children to school on Staten Island and is credited with rescuing at least 50 sailors from shipwrecks and capsized boats. She grew to love her isolated post, famously stating, “I am so much a part of this lighthouse that I feel as if it is a part of me… The light is my home.”

More Than Just a Light: The Daily Grind

The heroism of these women wasn’t only displayed during dramatic storms. It was woven into the fabric of their daily lives, which were characterized by relentless labor and profound isolation.

A keeper’s day was a cycle of demanding chores:

- Tending the Lamp: Carrying heavy fuel containers up many flights of stairs, sometimes several times a night.

- Maintaining the Lens: Cleaning the intricate glass of the Fresnel lens a task requiring hours of gentle, focused work to ensure maximum brilliance. Every speck of dust or soot could dim the life-saving beam.

- Winding the Clockwork: Many lights had a clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens, which had to be wound by hand, often every few hours.

- Upkeep and Records: Painting the tower to fight corrosion, repairing storm damage, and maintaining a meticulous daily log for the Lighthouse Service.

Beyond these official duties, they had to be completely self-sufficient. They raised children, gardened in salty soil, fished for food, and served as the sole doctor, teacher, and protector for their families in places where help was hours or even days away.

The Light Fades: The End of an Era

The 20th century brought changes that spelled the end for the civilian lighthouse keeper. The first blow was the institutional shift in 1939 when the U.S. Lighthouse Service was absorbed into the U.S. Coast Guard. The new military structure effectively barred women from being appointed as keepers. While some “grandmothered-in” women continued to serve for years, the path to the tower was closed.

The final blow was automation. As technology advanced, lighthouses no longer needed a constant human presence. One by one, the lamps were automated and the stations were de-staffed. The last civilian keeper in the United States, Fannie Salter of Turkey Point Light in Maryland, retired in 1947, closing the chapter on this remarkable history.

Today, as we see these beautiful, automated towers flashing their silent warnings across the water, it’s worth remembering the women who once inhabited them. They were not merely wives or assistants; they were dedicated professionals who braved loneliness and danger with unwavering commitment. For their courage and their service, Ida Lewis, Abbie Burgess, Kate Walker, and hundreds of others like them deserve to be remembered not as historical curiosities, but as true heroes of the American coast.