An Army of Minds

How did thousands of women end up at this Victorian country estate, engaged in the most secretive work of the war? Recruitment was a multi-pronged effort. The call went out to universities like Cambridge and Oxford, seeking the brightest female minds with degrees in mathematics, linguistics, and modern languages. Others were scouted from elite debutante circles, chosen for their perceived trustworthiness and discretion. Many more were recruited directly into the Women’s Royal Naval Service (Wrens) and the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) specifically for roles at “Station X” and its various outposts.

The selection process could be unconventional. One story, which has become legendary, tells of The Daily Telegraph running a cryptic crossword competition in 1942. The Secret Intelligence Service discreetly invited the fastest solvers to an interview, seeking out the kind of lateral-thinking minds needed for cryptanalysis. Several women were recruited this way, plucked from ordinary life and thrust into a world of extraordinary secrets.

From Interception to Intelligence: The Diverse Roles

The idea that women only performed administrative or “unskilled” work is a pervasive myth. In reality, they were involved at every single stage of the intelligence pipeline, from the initial interception of enemy signals to the final decryption and analysis.

The Listeners and Registrars

The process began far from the main house, at listening posts known as “Y-stations” scattered across Britain. Here, women of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) spent grueling hours listening to the faint crackle of Morse code. They had to transcribe endless streams of jumbled letters sent by German operators, a task requiring immense concentration and accuracy. A single missed letter could render a whole message useless.

Once the messages arrived at Bletchley, another army of women took over. They worked in the Registry, a vast library of secrets. They managed a colossal card index system that cross-referenced every scrap of information, from call signs of German radio operators to decrypted message fragments. This meticulous, painstaking work, often dismissed as mere clerical duty, was the foundation upon which the star cryptanalysts built their breakthroughs.

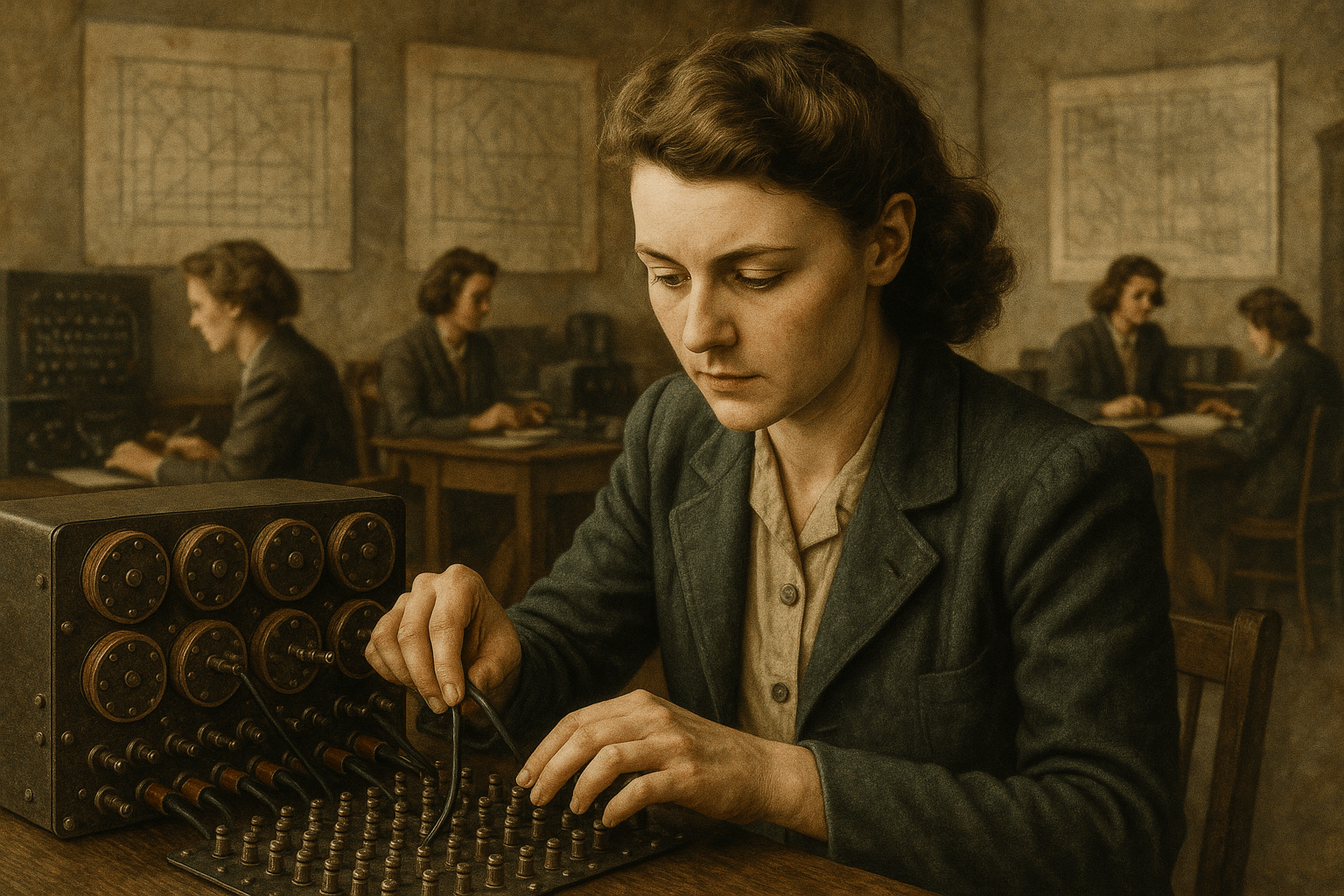

The Machine Operators

Perhaps the most iconic image of Bletchley’s machinery is the “Bombe”, the electromechanical device designed by Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman to find the daily settings for the Enigma machine. Operating these machines was physically and mentally demanding work, entrusted almost exclusively to Wrens. Standing for hours in noisy, poorly ventilated huts, they would plug in cables and set rotors according to a specific “menu” provided by the codebreakers. They listened for the machine to stop, indicating a potential correct setting, then meticulously checked and recorded it before resetting the machine to continue its search. Their tireless work turned theoretical cryptographic attacks into actionable, daily intelligence.

Later in the war, women also operated the Colossus machines, the world’s first programmable electronic computers, designed to break the more complex Lorenz cipher used by German High Command. These women were not just button-pushers; they had to rewire the machine for each new problem, becoming some of the earliest computer operators in history.

The Codebreakers: Cracking the Uncrackable

While many roles were highly operational, a significant number of women were at the forefront of cryptanalysis itself, working as fully-fledged codebreakers.

Joan Clarke

The most famous of Bletchley’s female codebreakers, Joan Clarke, was a brilliant mathematician recruited from Cambridge by her former geometry supervisor, Gordon Welchman. She joined Hut 8, the section focused on breaking Naval Enigma, and quickly became one of its most skilled practitioners, working alongside Alan Turing. Initially, she was classified and paid as a clerk due to her gender, a bureaucratic absurdity. To secure her a pay rise commensurate with her abilities, she was officially promoted to the grade of “Linguist”, even though she didn’t speak any other languages. Clarke’s contributions to breaking the notoriously difficult U-boat cipher, “Shark”, were crucial in turning the tide of the Battle of the Atlantic.

Mavis Batey (née Lever)

Mavis Batey was a German linguist who joined Dilly Knox’s team. Famously described as looking more like a “debenture a deb”, she possessed a razor-sharp intellect. In 1941, she made an astonishing breakthrough. Struggling to crack a message from the Italian Navy, she deduced that the operator, being lazy, had only used letters in the message itself to set the machine. With this insight, she reconstructed the entire wiring of the Italian naval Enigma machine. This intelligence was instrumental in the Royal Navy’s decisive victory at the Battle of Cape Matapan, a major turning point in the Mediterranean.

Margaret Rock

Working alongside Dilly Knox and Mavis Batey, Margaret Rock was another senior cryptanalyst. Having worked as a statistician before the war, her methodical approach was vital. She was one of the first people to decrypt signals from the German Secret Service’s Enigma machine and made significant contributions to breaking the Abwehr cipher, helping to unravel Germany’s spy networks across Europe.

A Legacy of Silence

After the war, the Bletchley Park operation was shut down, its machines destroyed, and its records sealed. The thousands of women who had worked there were bound for life by the Official Secrets Act. They returned to civilian life, unable to speak of their monumental achievements to anyone, not even their closest family. Their wartime experiences were reduced to a vague “I did some secretarial work” or “I was in the Wrens.”

It wasn’t until the 1970s that the first details of Bletchley Park’s work began to emerge, and only in recent decades has the full scale of the female contribution been truly appreciated. These women were not just cogs in a machine; they were the listeners, the organizers, the operators, and the masterminds whose combined efforts shortened the war by an estimated two to four years, saving countless lives. They are the unsung heroines of World War II, and their story is a powerful testament to the extraordinary capabilities that were hidden in plain sight.