Imagine standing in the heart of the Iranian plateau, the sun beating down with an intensity that bakes the very air you breathe. In this arid landscape, where summer temperatures can soar to blistering heights, how did ancient civilizations thrive? Long before the hum of electric fans and the energy-guzzling chill of modern air conditioning, Persian architects devised a solution of breathtaking elegance and ingenuity: the Bâdgir, or “wind-catcher.” These magnificent towers, rising like sentinels from the rooftops of cities, are a testament to a deep understanding of natural forces and a masterful application of sustainable design.

Anatomy of an Ancient Air Conditioner

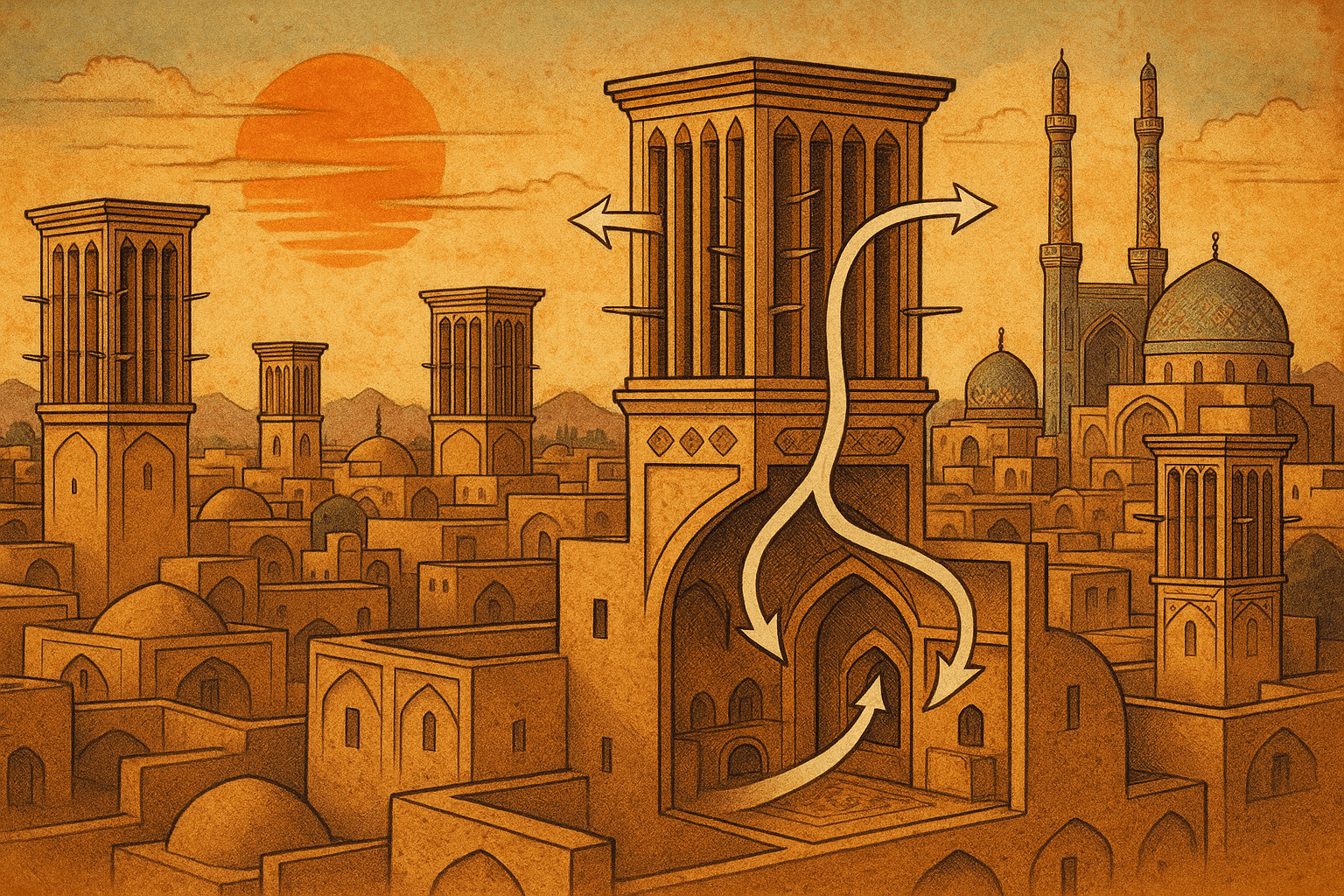

At first glance, a Bâdgir (pronounced “bawd-geer”) appears as a simple rectangular or multi-sided tower protruding from a building’s roof. Yet, this simple form belies a complex and highly effective internal structure. The tower is capped with several directional vents, or openings, which are partitioned from each other. Below these vents, a series of vertical shafts descend directly into the rooms below, often leading to a main hall or a basement space known as the sardāb.

These towers were not monolithic in design; their form was dictated by the local climate and prevailing wind patterns. In regions with winds from a single dominant direction, one-sided Bâdgirs were common. In cities like Yazd, famous for its forest of wind-catchers, four-sided or even eight-sided towers were built to capture breezes from any direction. The height of the tower was also critical, as it allowed it to catch stronger, cooler winds found at higher elevations, free from the dust and heat of the street level.

The Genius of Passive Cooling

The magic of the Bâdgir lies in its ability to harness natural physics to create a comfortable indoor environment. It operates on two primary principles, allowing it to function both on windy and on completely still days.

Principle 1: Funneling the Breeze

On a day with even a slight breeze, the Bâdgir operates in its most straightforward mode. The openings on the windward side of the tower “catch” the passing air and funnel it down the internal shaft. This stream of air is pushed into the living spaces below, creating a cooling draft. As this fresh air enters, it displaces the warmer, stale air inside the building, which is then pushed out through other windows, doors, or even up a different shaft of the same Bâdgir facing away from the wind. This continuous cycle of intake and exhaust provides constant, natural ventilation.

Principle 2: The Solar Chimney Effect

But what about those sweltering, windless days? This is where the true genius of the design shines. The Bâdgir tower, often built of heat-absorbing materials like brick or adobe, is heated by the sun. The column of air inside the tower becomes warmer and therefore less dense than the air in the rooms below. This causes the hot air to rise and escape out of the top of the tower, a phenomenon known as the stack effect.

This upward movement of air creates a pressure difference, effectively sucking air out of the building. To replace it, cooler air is drawn into the home from lower-level openings, such as shaded courtyards or cool basements. This creates a gentle, continuous airflow even in the absence of wind, preventing the interior from becoming hot and stagnant.

The Masterstroke: Synergy with the Qanat

Persian engineers elevated this system from a simple ventilator to a true evaporative cooler by integrating it with another marvel of ancient engineering: the qanat. A qanat is a subterranean aqueduct, a gently sloping underground tunnel that taps into an alluvial aquifer and transports water over many kilometers using only gravity.

Many wealthy homes and important buildings were strategically built over a qanat. The Bâdgir’s down-draft shaft would extend all the way down to this cool, subterranean space. As the hot, dry desert air was channeled down the tower, it would pass over the cool stream of water flowing in the qanat. This process caused two things to happen:

- The air was significantly cooled through heat exchange with the cold water.

- Moisture evaporated from the water’s surface, humidifying the air.

The result was a current of air that was not just moving, but actively chilled and pleasantly humidified—a true, pre-electric air conditioner. Residents could gather in these basement rooms, cooled by a breeze that could be up to 15°C (27°F) cooler than the outside air.

A Legacy Written in the Skyline

While the exact origins are debated by historians, archaeological evidence suggests wind-catching structures existed in Persia (modern-day Iran) and Egypt thousands of years ago. The city of Yazd in Iran, however, stands as the quintessential “City of Wind-Catchers” (Shahr-e Bâdgirha). Its historic skyline is a breathtaking panorama of these earthen towers, each a silent monument to centuries of architectural wisdom. The Dowlatabad Garden in Yazd is home to a 33-meter-high Bâdgir, a UNESCO World Heritage site and a stunning example of the form’s elegance and scale.

The Bâdgir was more than just a functional utility; it was a status symbol. The size, height, and complexity of a home’s wind-catcher were often a direct reflection of the owner’s wealth and social standing. The technology spread along trade routes, and variations can be found in Pakistan (where they are called mungh), Afghanistan, and across the Arab states of the Persian Gulf.

In an era grappling with the immense energy costs and environmental impact of modern HVAC systems, the ancient Bâdgir offers a profound lesson. It represents a model of sustainable design that works in harmony with its environment rather than fighting against it. These structures are a powerful reminder that sometimes, the most sophisticated solutions are not born from new technology, but from a timeless, intelligent observation of the natural world.