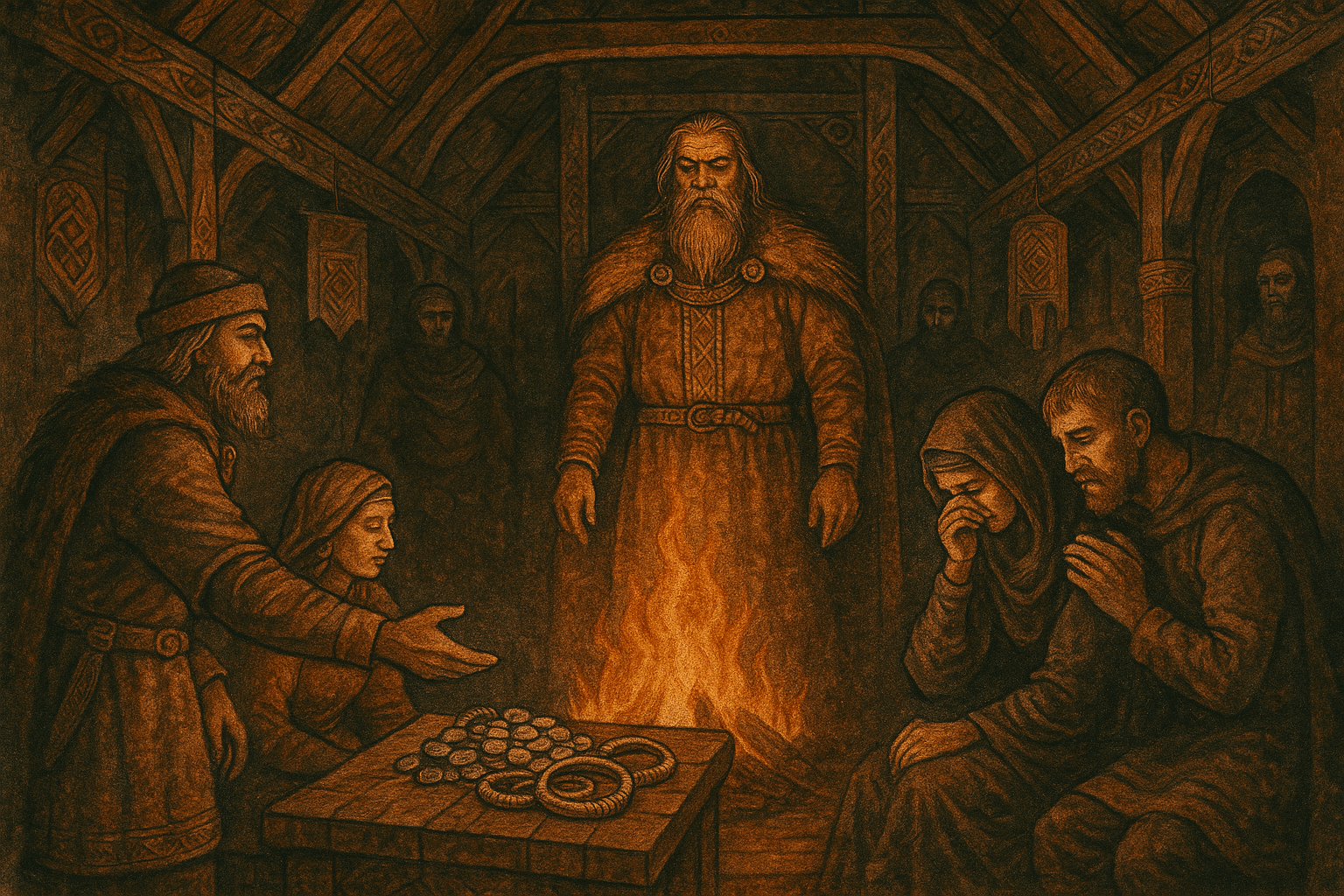

Imagine a smoky longhouse in 7th-century England. A dispute over a game of dice or a boast made in drink escalates. Swords are drawn, and in a flash of violence, a man lies dead on the packed-earth floor. In our modern world, the next steps are clear: police, an investigation, a trial, and likely, a prison sentence. But in the world of the early Germanic tribes—the Angles, Saxons, Franks, and Goths—the path to justice was radically different. There were no prisons, no police force as we know it. Instead, there was a price. This was the world of the wergild.

What Was the Wergild?

The term wergild, from Old English and other Germanic languages, translates literally to “man-price” or “man-payment.” It was a sophisticated system of legal restitution at the heart of early Germanic law. Instead of punishing an offender through incarceration or execution (though execution did exist for certain crimes like treason), the law focused on compensation. If you injured or killed someone, you—and your extended family—owed a debt to the victim’s family. The wergild was the legally defined value of that person’s life, paid to prevent a far more destructive outcome: the blood feud.

This system wasn’t about forgiving the crime; it was about staunching the bleeding. In a society structured around kinship and honor, an attack on one member was an attack on the entire clan. The natural response was revenge, a vendetta that could trigger a horrifying and destabilizing cycle of tit-for-tat killings, weakening all families involved. The wergild offered an honorable, legally sanctioned alternative. Paying it restored the material loss to the victim’s kin and, just as importantly, satisfied their honor, making vengeance unnecessary.

A Price for Every Person

The core of the wergild system was a detailed, and to modern eyes, brutally pragmatic tariff for human life and limb. Not all lives were valued equally; a person’s wergild was a direct reflection of their social status. This hierarchy was the spine of the legal codes.

Across the Germanic world, from Anglo-Saxon England to the Frankish kingdoms, the pattern was similar:

- Royalty and High Nobility: A king’s life was considered almost priceless, his wergild astronomically high to make regicide unthinkable. In the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia, a king’s wergild was 7,200 shillings, a colossal sum. A high-ranking noble, or ealdorman, had a wergild many times that of a commoner.

- The Freeman (Ceorl): The standard freeman, the backbone of society, had the baseline wergild. In most of England, this was set at 200 shillings. This was still a significant amount, often paid in livestock, weapons, or land, and could spell financial ruin for a family.

- The Noble (Thegn): A lesser noble or aristocratic warrior, known as a thegn in England, was typically valued at 1,200 shillings—six times the value of a freeman. Their importance to the king as military retainers was reflected in their high man-price.

- Foreigners and Other Ranks: The wergild for a Welshman in English territory was often lower than that of a Saxon. The clergy also had their own specific values, with an archbishop’s life valued higher than a king’s in some codes, reflecting the power of the Church.

- The Enslaved: An enslaved person (a thrall) typically had no wergild. Killing a slave was not seen as murder but as destruction of property. The payment went not to the slave’s family, but to their owner.

The Grisly Price List of a Broken Body

The legal codes didn’t just cover death. They contained incredibly specific lists for non-lethal injuries, a system known as bot. The Laws of Æthelberht of Kent, written around 602 AD, provide a stunningly detailed glimpse into this practice. Everything had a price, calculated with grim precision:

- Losing an eye: 50 shillings

- Losing a foot: 50 shillings

- Making a person deaf: 25 shillings

- Breaking a thigh: 12 shillings

- Knocking out a front tooth: 6 shillings

- Knocking out a molar: 1 shilling

- Losing a thumbnail: 3 shillings

- Even pulling someone’s hair was fineable.

This system reveals what the society valued. An eye was worth a foot, a front tooth was six times more valuable than a back tooth (likely due to its visible impact on appearance), and the hands and feet, vital for a warrior or farmer, carried the highest prices next to life itself.

Putting the System into Practice

Administering the wergild was a community affair. After an offense, elders and community leaders would likely mediate. The offender and their kin were collectively responsible for raising the payment. Likewise, the victim’s family collectively received it. This reinforced kinship bonds and the idea of mutual responsibility that held society together.

If an offender refused or was unable to pay, the consequences were dire. They could be declared an outlaw—a “wolf’s-head.” This meant they were stripped of all legal protection. Their property could be seized, and anyone could kill them without fear of repercussion; there would be no wergild for an outlaw. The threat of becoming a legal non-person was a powerful incentive to find a way to pay.

In addition to the wergild (paid to the family), there was often a separate fine called a wite, which was paid to the king or local lord. This was a payment for breaking the “King’s Peace” and represents the early seeds of state-led justice, where crime is seen as an offense against public order, not just a private individual.

The Decline of the Man-Price

For centuries, the wergild was the bedrock of Germanic justice. So why did it disappear? The same forces that built medieval Europe spelled its end.

The primary factor was the rise of centralized state power. As kings and rulers consolidated their authority, they began to view crime differently. A murder was no longer just an offense against a kin-group; it was an offense against the state and the authority of the king. Justice shifted from compensation to punishment. The fines that were once paid to the victim’s family (wergild) were increasingly redirected to the king’s treasury (wite), becoming a source of royal revenue.

The influence of the Christian Church also played a crucial role. While early on the Church incorporated wergild into its own laws, its teachings on sin, divine judgment, and the state’s God-given right to punish wrongdoing pushed society away from simple monetary exchange. An offense against God and the community required penance and punishment, not just payment.

By the High Middle Ages, the wergild system had largely faded, replaced by manor courts, royal justice, and a legal framework that looks much more familiar to us today. But its legacy endures as a fascinating example of a society that engineered a complex legal system to maintain order, balance honor, and literally make offenders pay the price for their crimes—not with their time, but with their treasure.