Nestled in the modern-day state of Bihar, the Nalanda Mahavihara, or great monastery, was more than just a place of religious instruction. From the 5th to the 12th century CE, it was arguably the world’s first great residential university, an intellectual powerhouse that attracted the brightest minds from as far away as China, Tibet, Korea, and Central Asia.

The Birth of a Legendary Institution

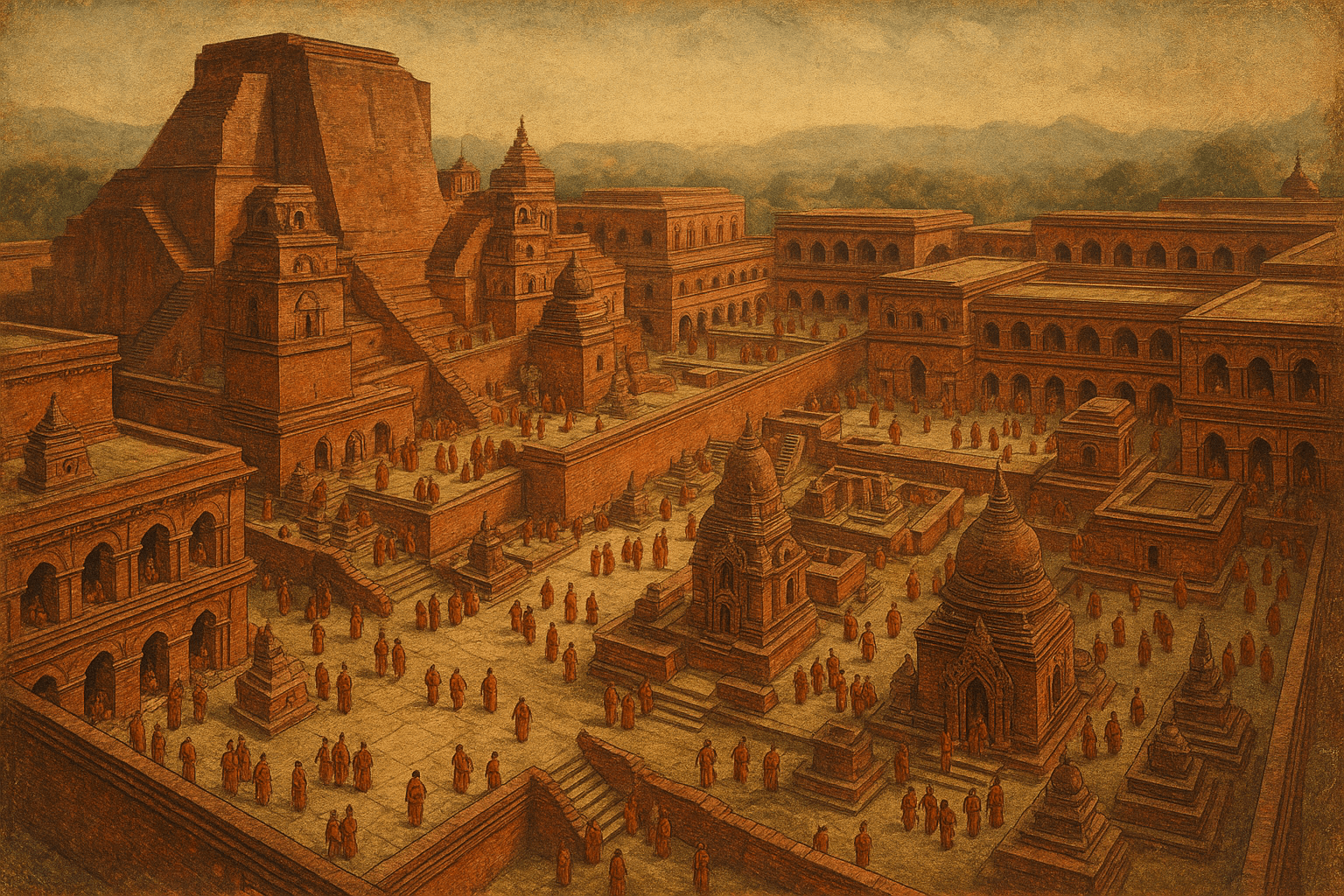

While legends attribute its origins to the time of the Buddha, archaeological evidence points to Nalanda’s flourishing during India’s “Golden Age” under the Gupta Empire around the 5th century CE. The Guptas, known for their patronage of art, science, and religion, laid the foundation for an institution that would outlive their dynasty by centuries. Subsequent rulers, most notably King Harshavardhana of Kannauj in the 7th century and the Pala emperors from the 8th to the 12th centuries, continued this tradition of royal patronage. They funded the construction of magnificent new temples (chaityas) and monasteries (viharas), ensuring Nalanda had the resources to grow into a sprawling academic metropolis.

The very name “Nalanda” is believed to mean “Giver of Knowledge” or “Insatiable in Giving”, a title it lived up to throughout its long and storied history.

A Glimpse into Campus Life

Thanks to the detailed accounts of travelling scholars like the Chinese monk Xuanzang, who studied at Nalanda in the 7th century, we have a vivid picture of what life was like within its red-brick walls. At its zenith, the university was home to an estimated 10,000 students and 2,000 teachers. The campus was a marvel of planning, featuring at least eight separate compounds, ten temples, numerous meditation halls, and lush parks and lakes.

Admission was notoriously difficult. Xuanzang noted that prospective students were questioned by gatekeeper-scholars on complex topics of philosophy and science. Only two or three out of every ten applicants were deemed worthy of entry. Once admitted, students were provided with free lodging, food, clothing, and tuition—all funded by royal endowments and donations from surrounding villages. This allowed scholars to dedicate themselves completely to their studies, engaging in a disciplined routine of lectures, meditation, and, most importantly, debate.

The Harvard of Ancient Asia: Curriculum and Scholars

Nalanda’s curriculum was remarkably diverse and comprehensive, attracting students from different Buddhist and non-Buddhist traditions. While its core focus was on Mahayana Buddhist philosophy, the pursuit of knowledge was never limited. The curriculum was a truly liberal arts education for its time. Subjects taught included:

- Buddhist Philosophy: Detailed study of both Mahayana and Hinayana schools.

- The Vedas: A deep dive into Hindu scriptures, crucial for understanding and debating opposing philosophical viewpoints.

- Logic (Nyaya): The art of reasoning and debate was a cornerstone of Nalanda’s pedagogy.

- Sanskrit Grammar: Mastery of the language of scholarship was essential.

- Medicine (Ayurveda): The campus included medical facilities where students learned the principles of traditional Indian medicine.

- Mathematics & Astronomy: Scholars at or near Nalanda, like the famed Aryabhata, made groundbreaking contributions to these fields.

- Metaphysics, Fine Arts, and Law.

The academic culture was dominated by shastrartha, or public debate. These intellectual contests were the primary method for establishing the validity of a thesis and were a spectacle of erudition and quick thinking. The university’s fame was built on its teachers, the panditas, who were titans of intellect. Figures like Dharmapala and Shilabhadra (Xuanzang’s own esteemed teacher) were celebrated across Asia for their wisdom and scholarship.

The Library of World Knowledge: Dharmaganja

Perhaps the most breathtaking feature of Nalanda was its colossal library, known as the Dharmaganja (Treasury of Truth). It wasn’t a single building but a complex of three magnificent, multi-storied structures:

- Ratnasagara (Ocean of Jewels)

- Ratnodadhi (Sea of Jewels), which was said to be nine stories high and housed the most sacred manuscripts.

- Ratnaranjaka (Delight of Jewels)

This library contained hundreds of thousands of handwritten manuscripts on palm leaves, covering every subject imaginable from religion and philosophy to astronomy and medicine. It was a repository of collected wisdom from India and beyond. Scholars meticulously copied, translated, and studied these texts, ensuring the preservation and dissemination of knowledge. The destruction of this library was one of the greatest intellectual tragedies in world history.

The End of an Era: Decline and Destruction

After 700 years of continuous operation, Nalanda’s star began to wane. The decline of Buddhism in India, coupled with the withdrawal of lavish royal patronage during the later Pala dynasty, weakened the institution. However, the final, catastrophic blow came around 1193 CE.

A Turkic army led by the chieftain Bakhtiyar Khilji swept through the region on a campaign of conquest. According to the Persian historian Minhaj-i-Siraj in his text, the Tabaqat-i-Nasiri, Khilji’s forces ransacked the university, mistaking the robed monks for “shaven-headed Brahmins” and the fortress-like structure for a military fort. The monks were slaughtered, and the great libraries were set ablaze.

The historian recounts that “smoke from the burning manuscripts hung for days like a dark pall over the low hills.” The library, which took centuries to build, allegedly burned for months, its irreplaceable knowledge turning to ash.

With this single act of brutal destruction, the light of Nalanda was extinguished. The surviving monks fled to Tibet and other regions, carrying with them what little knowledge they could save. The university was abandoned, and its magnificent ruins were slowly reclaimed by the earth, forgotten for nearly 600 years.

Nalanda’s Enduring Legacy

Rediscovered by British archaeologists in the 19th century, the excavated ruins of Nalanda are now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a silent testament to a glorious past. Yet, its legacy is more than just bricks and mortar. Nalanda represents a universal ideal: the creation of a multicultural, international space dedicated purely to the pursuit of knowledge, critical thinking, and open debate.

In a fitting tribute, the modern Nalanda University was inaugurated in 2014 near the ancient site, an international effort to revive the spirit of its namesake. As we look at the excavated monasteries and temples today, we are reminded that Nalanda was not just an ancient Indian university; it was a gift to the world, a symbol of a time when knowledge was truly borderless.