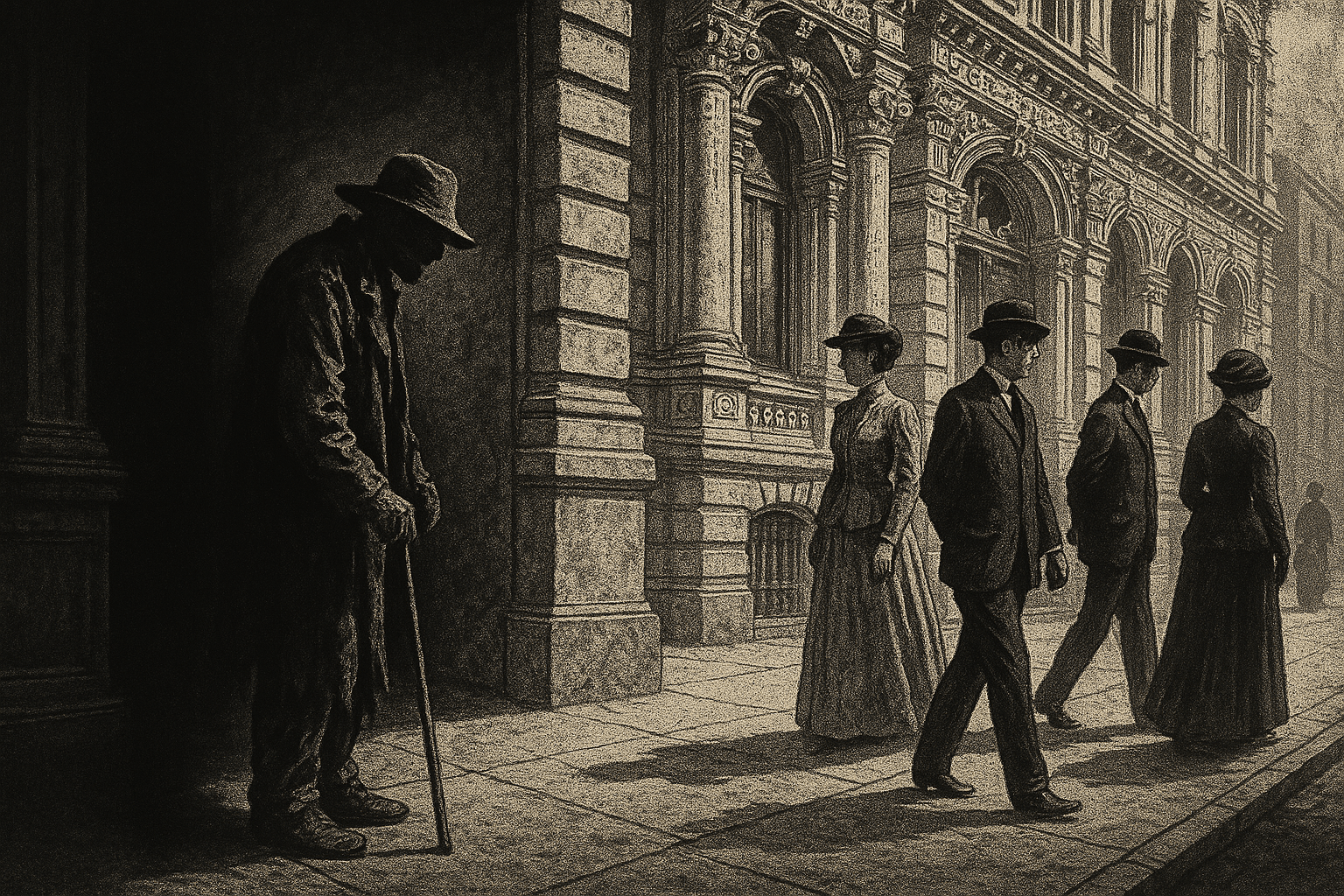

Imagine strolling through a bustling American city in the late 19th or early 20th century. The air hums with the energy of industry, the streets are crowded with people, and the nation is forging its modern identity. But beneath this veneer of progress, a dark and discriminatory legal framework was taking hold. In cities across the country, it was becoming illegal for certain people to simply be seen in public. These were the “unsightly beggar ordinances,” more commonly and chillingly known as “Ugly Laws.”

What Were the ‘Ugly Laws’?

The name itself is shocking, and the text of the laws is even more so. Chicago enacted one of the most famous and long-lasting ordinances in 1881. It stated:

“No person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object, or an improper person to be allowed in or on the public ways or other public places in this city, shall therein or thereon expose himself to public view, under a penalty of a fine of not less than one dollar nor more than fifty dollars for each offense.”

This language was not unique to Chicago. Cities from San Francisco, California, to Portland, Oregon, and from Omaha, Nebraska, to New Orleans, Louisiana, adopted similar ordinances. The target was clear: anyone whose physical appearance was deemed offensive to the public eye. This predominantly included individuals with visible disabilities, the visibly impoverished, and those bearing the scars of war or disease. They were, in effect, criminalized for their very existence in the shared spaces of the city.

The Social Anxieties of a Changing Nation

To understand why these laws emerged, we must look at the historical context of the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era. This was a period of immense social upheaval.

Industrialization and Urbanization: Cities were growing at an unprecedented rate, filled with factories, tenements, and a flood of new migrants and immigrants. This rapid, often chaotic growth created anxieties among the established middle and upper classes about social order, sanitation, and public decorum. The visible presence of poverty and disability was seen not as a social issue needing compassion, but as a blight on the city’s modern, orderly image.

The Aftermath of the Civil War: The nation was still grappling with the human cost of the Civil War. A generation of men returned home with life-altering injuries and disabilities. Many were unable to find work and resorted to begging on street corners. These veterans, once hailed as heroes, were now often seen as a public nuisance, their visible wounds a constant, uncomfortable reminder of the war’s brutality.

The Rise of Eugenics: The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of eugenics, a dangerous and discriminatory pseudoscience focused on “improving” the human race through selective breeding. Eugenicists promoted the idea that traits like poverty, criminality, and disability were hereditary and that those who possessed them were “unfit.” Ugly Laws were a practical application of eugenicist thought, aiming to remove these “unfit” individuals from the public sphere, thereby “purifying” public life and discouraging their presence and perceived influence.

Life Under the Shadow of the Law

For those targeted, the Ugly Laws were a constant threat. Enforcement was often arbitrary, left to the discretion of a police officer on the beat. A person with a severe facial scar, a congenital condition, a missing limb, or even just ragged, dirty clothing could be arrested, fined, or jailed. The laws effectively denied them their right to move freely, to seek work, or to participate in public life.

In 1874, San Francisco arrested a man named Martin Oates, a former soldier whose face had been disfigured in the war. He was charged under a city ordinance that mirrored the later Ugly Laws. His case highlights the cruel irony faced by many veterans. The very injuries sustained in service to their country now made them targets of legal persecution.

These laws forced a whole segment of the population into the shadows. People with disabilities were encouraged to stay home or were institutionalized, hidden away from a society that deemed them “unsightly.” It institutionalized ableism and reinforced the idea that a person’s worth was tied to their physical appearance and their ability to conform to a narrow standard of normalcy.

The Slow Repeal and Lasting Legacy

The Ugly Laws were not struck down in a single, sweeping court decision. Instead, they slowly faded from use over the mid-20th century as social attitudes began to shift. The rise of the disability rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s was a critical turning point. Activists began to challenge the deep-seated prejudice and systemic discrimination that people with disabilities faced, demanding not to be hidden away but to be included as full and equal members of society.

This new consciousness made the Ugly Laws appear for what they were: relics of a prejudiced and ignorant past. Yet, they remained on the books for a shockingly long time. Chicago, the city with one of the first ordinances, was also the last to repeal it, finally doing so in 1974.

The passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990 can be seen as the ultimate repudiation of the philosophy behind the Ugly Laws. The ADA legally mandated accessibility and prohibited discrimination against people with disabilities, enshrining into federal law the very rights the Ugly Laws sought to deny.

Though they are now a forgotten chapter of American history, the Ugly Laws serve as a powerful reminder of how easily prejudice can be codified into law. Their legacy lingers in modern debates over who is welcome in public spaces, seen in the rise of “hostile architecture” designed to deter the homeless and in ordinances that criminalize poverty. By remembering the Ugly Laws, we are reminded of the constant vigilance required to ensure our public squares are truly public, open and welcoming to all, regardless of appearance, ability, or economic status.