Beyond the Myth of a Monolithic Empire

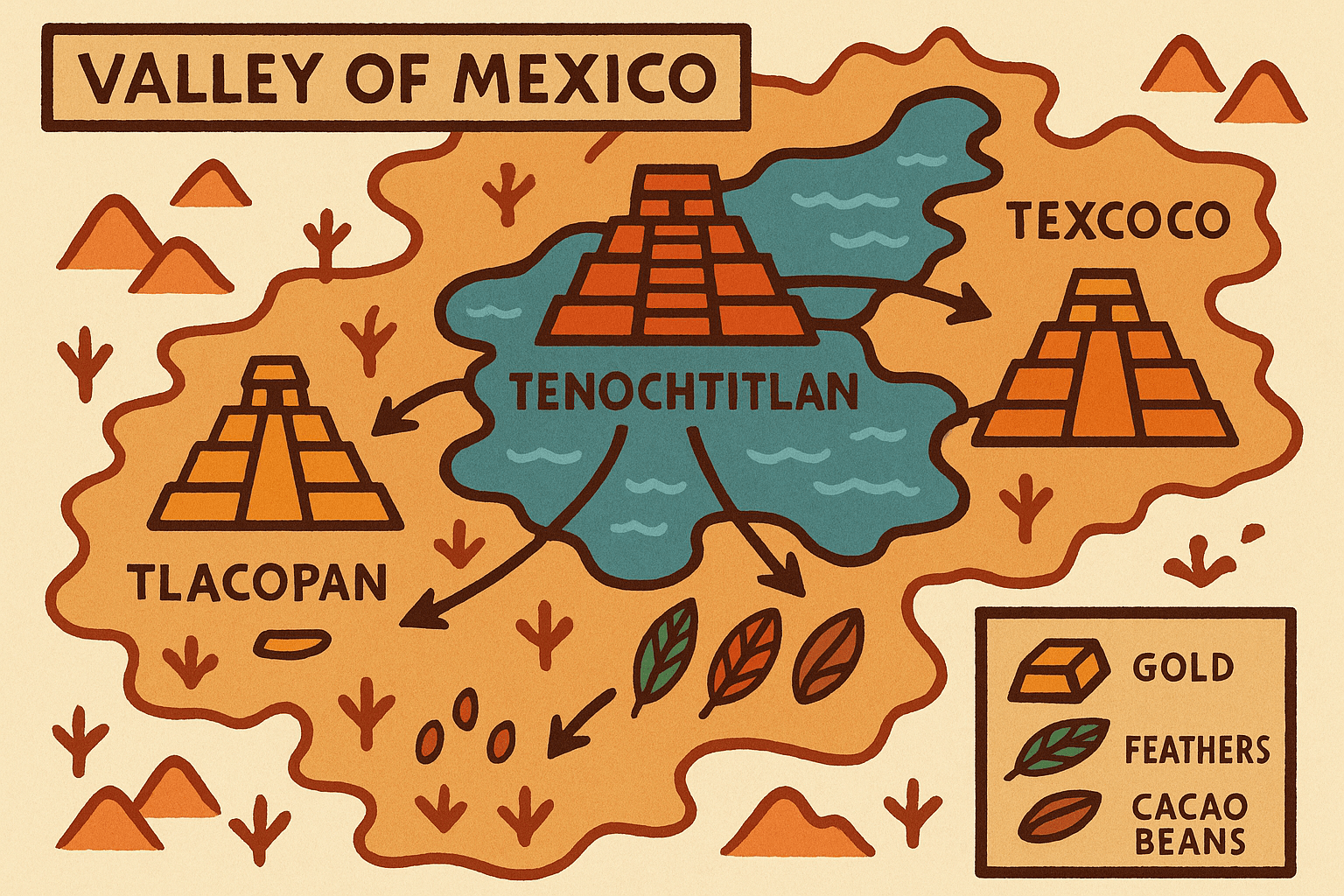

When we hear the term “Aztec Empire,” our minds often conjure images of a single, unified kingdom ruled from a magnificent capital, a Mesoamerican Rome dominating all in its path. But reality, as is often the case in history, was far more complex and fascinating. What we call the Aztec Empire was, for most of its existence, not an empire in the traditional sense. It was a strategic and often tense military and economic confederation of three distinct city-states: Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. This was the Triple Alliance, the true power behind the Aztec phenomenon that dominated central Mexico before the arrival of Hernán Cortés.

To understand the world the Spanish encountered in 1519, we must first peel back the layers of this intricate political arrangement, a system of shared power, tribute, and simmering rivalry.

The Ashes of Tyranny: Forging the Alliance

The Triple Alliance was born from war and rebellion. In the early 15th century, the Valley of Mexico was controlled by the powerful Tepanec Empire, ruled from the city-state of Azcapotzalco. The Mexica of Tenochtitlan, the Acolhua of Texcoco, and the people of Tlacopan were all subjects, chafing under the oppressive reign of the Tepanec ruler, Maxtla.

The breaking point came around 1428. Following the assassination of his father, the brilliant prince of Texcoco, Nezahualcoyotl, was driven into exile. He found common cause with Itzcoatl, the ambitious new ruler of Tenochtitlan. Together, they forged a coalition to overthrow their shared oppressor. They convinced the city of Tlacopan, a disgruntled Tepanec city, to switch sides, and together the three powers waged a successful war against Azcapotzalco. When the Tepanec capital fell, the victors didn’t just replace the old tyrant—they created a new world order. This new order was the Triple Alliance, or *Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān*.

A Three-Headed Power: The Roles of the Cities

From its inception, the alliance was not a partnership of equals. The power dynamics and division of spoils were clearly defined, reflecting each city’s contribution to the war and its ongoing role in the new empire.

The tribute—the lifeblood of the empire—was formally divided as follows:

- Two-fifths (40%) for Tenochtitlan

- Two-fifths (40%) for Texcoco

- One-fifth (20%) for the junior partner, Tlacopan

Beyondsimple economics, each city held a specific, though unofficial, role within the confederation:

Tenochtitlan: The Military Might. Home of the fierce Mexica people, Tenochtitlan was the undisputed military leader of the alliance. Its ruler, the *Huey Tlatoani* (“Great Speaker”), served as the commander-in-chief of the allied armies. The Mexica were the enforcers, leading the campaigns of conquest that expanded the empire’s borders. Their god, Huitzilopochtli, was a deity of war and sun, perfectly aligning with their martial responsibilities. Over time, the *Huey Tlatoani* of Tenochtitlan would become the *de facto* head of the entire empire.

Texcoco: The Intellectual Heart. If Tenochtitlan was the brawn, Texcoco was the brain. Renowned for its culture, engineering, and legal system, Texcoco was considered the “Athens of the Anahuac Valley.” Its rulers, most famously the poet-king Nezahualcoyotl, were celebrated as lawgivers, philosophers, and patrons of the arts. Texcoco’s courts were the highest in the land, and its engineers designed critical infrastructure like the dikes and aqueducts that served the entire region. It provided the legal and intellectual framework that gave the empire a veneer of sophisticated civilization.

Tlacopan: The Strategic Partner. As the junior member, Tlacopan’s role was less glamorous but politically vital. Having been a Tepanec city, its inclusion in the alliance helped legitimize the new power structure and integrate former enemy territory. It provided troops and logistical support for military campaigns and ensured a stable balance of power, preventing a direct two-way rivalry between the powerful states of Tenochtitlan and Texcoco.

The Engine of Empire: The Tribute System

The Triple Alliance did not rule by direct occupation. Conquered city-states, known as *altepetl*, were typically left with their local rulers and customs intact. Their defeat, however, came at a price: the regular payment of tribute.

This tribute was the economic engine that fueled the wealth and splendor of the capital cities. The demands were systematic and meticulously recorded in documents like the famous *Codex Mendoza*. Depending on the region, a conquered province might be required to send:

- Foodstuffs: Vast quantities of maize, beans, amaranth, and chia to feed the burgeoning populations of the capital cities.

- Raw Materials: Lumber, lime, and reeds for construction.

- Luxury Goods: Jade, turquoise, gold dust, brilliant tropical bird feathers (especially from the Quetzal), and jaguar pelts.

- Manufactured Goods: Intricately decorated warrior costumes, shields, pottery, and textiles.

Failure to pay tribute was met with swift and brutal retaliation from the Triple Alliance’s armies. The threat of military force was the glue that held this vast economic network together. This system allowed the core cities to become fabulously wealthy, but it also sowed deep seeds of resentment among the subjugated peoples.

Cracks in the Foundation: Rivalry and the Rise of Tenochtitlan

For decades, the alliance functioned as an effective system of shared hegemony. However, it was not a harmonious union of friends. It was a pragmatic arrangement built on mutual self-interest, and beneath the surface, rivalries simmered.

As the 15th century drew to a close, the balance of power began to shift decisively in favor of Tenochtitlan. The Mexica’s military dominance translated into ever-increasing political influence. While the tribute shares officially remained the same, the *Huey Tlatoani* of Tenochtitlan began acting less like a first-among-equals and more like a sole emperor. Moctezuma II, who ascended to the throne in 1502, consolidated power significantly, making decisions about war and foreign policy with less and less consultation with his “allies” in Texcoco and Tlacopan.

This growing Mexica arrogance caused friction. There were succession disputes within the royal houses, policy disagreements, and a general feeling in Texcoco that its cultural and legal authority was being overshadowed by Tenochtitlan’s brute force. The alliance was becoming, in essence, a Tenochtitlan-centric empire in all but name.

The Eve of Conquest

When Hernán Cortés and his small band of conquistadors landed in 1519, they did not walk into a unified, monolithic empire. They walked into a complex political landscape defined by the Triple Alliance—an alliance that was already showing signs of strain. More importantly, they found an “empire” surrounded by enemies and resentful subjects. Peoples like the Tlaxcalans, who had fiercely resisted Aztec domination for decades, saw the Spanish not as invaders, but as powerful potential allies against their hated Mexica overlords.

The genius of Cortés was not just his military audacity, but his political cunning. He quickly understood the intricate web of rivalries and resentments. He exploited the cracks within the Triple Alliance and expertly fueled the flames of rebellion among its tributary peoples. The fall of Tenochtitlan was not the conquest of an empire by a few hundred Spaniards; it was the collapse of a hegemonic system, brought down by a massive indigenous uprising led, armed, and directed by the Spanish. The Triple Alliance, born in a war of liberation, was ultimately consumed by another one.