From Conqueror to Patron: The Paradox of Timur

Timur’s method was as paradoxical as it was effective. As his armies swept across Persia, India, and the Levant, he left widespread destruction in his wake. In a city marked for conquest, much of the general populace was often put to the sword. However, a specific group was almost always spared: the artisans. Master builders, tile-makers, calligraphers, scientists, poets, and scholars were identified, rounded up, and forcibly deported back to Samarkand.

Timur was not merely a collector of talent; he was a visionary with a grand design. He sought to build a capital that would have no equal on Earth, a city that would embody his power and legitimize his dynasty. By concentrating the greatest minds and hands of the conquered lands in one place, he created a crucible of creativity. Persian aesthetics, Indian craftsmanship, and Central Asian traditions merged, birthing a new, uniquely Timurid style defined by grandeur, mathematical precision, and breathtaking beauty.

The Azure City: Architecture of Power and Piety

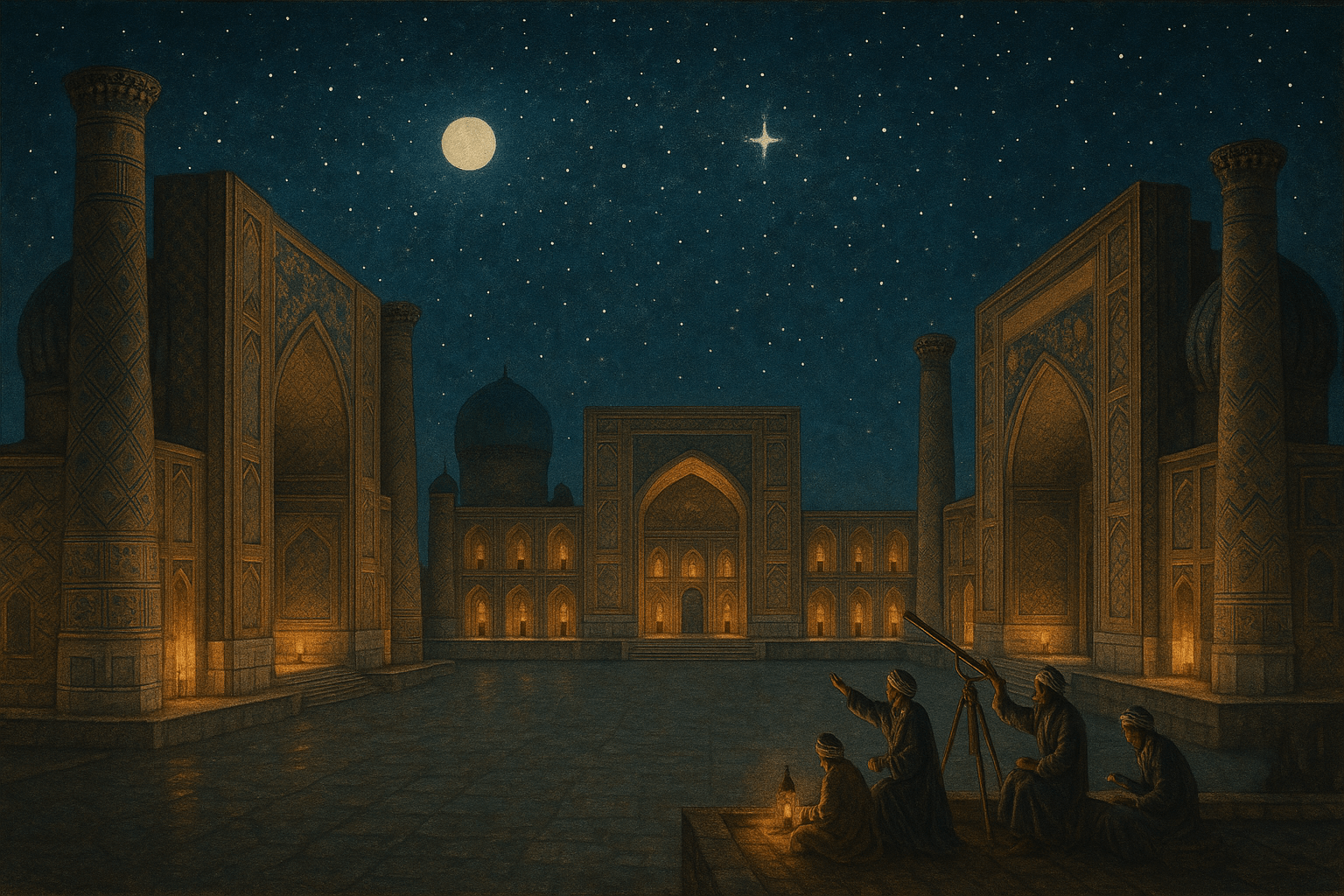

Nowhere is the Timurid Renaissance more tangible than in the architecture of Samarkand. Timurid buildings were designed to awe and overwhelm, communicating imperial might through sheer scale and opulent decoration. Key features that came to define this golden age include:

- Monumental Scale: Immense portals (iwans), soaring minarets, and vast courtyards were standard.

- Iconic Domes: Double-shelled and often ribbed or fluted, the brilliant turquoise and azure “melon domes” became the signature of the Timurid skyline.

- Intricate Tilework: Façades were covered in a symphony of glazed tiles. The Timurids perfected techniques like cuerda seca (dry cord) and mosaic faience to create complex geometric patterns, floral motifs, and masterful Kufic calligraphy that seemed to float on a sea of blue.

The crown jewels of this architectural boom remain legendary. The Bibi-Khanym Mosque, built by Timur after his campaign in India, was intended to be the grandest mosque in the Islamic world. Its turquoise dome was compared to the vault of heaven and its main portal to the Milky Way. So ambitious was its construction that it pushed 15th-century engineering to its limits and began suffering from structural problems within years—a testament to Timur’s relentless drive for greatness.

Perhaps the most iconic structure is the Gur-e-Amir, Timur’s own mausoleum. Its magnificent fluted azure dome dominates the skyline, and its interior is a treasure box of gilded papier-mâché, onyx panels, and jasper. It established an architectural precedent that would echo for centuries, most famously providing the direct inspiration for the great Mughal tombs of India, including the Taj Mahal.

The Stars from Samarkand: Science and Scholarship

The renaissance was not limited to stone and tile. Under Timur’s successors, particularly his grandson Ulugh Beg, Samarkand became a world-leading center for science and astronomy. While Timur had been a man of war, Ulugh Beg was a man of the mind—a gifted astronomer, mathematician, and patron of learning who preferred the observatory to the battlefield.

In the 1420s, Ulugh Beg commissioned the construction of the Samarkand Observatory, a three-story marvel of scientific engineering. Its primary instrument was the Fakhri sextant, an enormous marble arc with a radius of over 40 meters, embedded deep in the earth. This colossal device allowed astronomers to measure the meridian transit time of celestial bodies with unprecedented accuracy. Using this and other instruments, Ulugh Beg and his team of scholars charted the heavens.

The result of their work was the Zij-i-Sultani, a star catalogue published in 1437. It documented the positions of 1,018 stars with a degree of precision not surpassed in the Western world until the work of Tycho Brahe nearly 150 years later. It also calculated the length of the sidereal year with remarkable accuracy, with a deviation of less than a minute from modern calculations. The Zij became one of the most important astronomical texts of the medieval world, profoundly influencing European, Indian, and Persian science for centuries.

The Art of the Book: Miniature Painting and Calligraphy

While Samarkand was the initial center, the artistic momentum continued in other Timurid courts, especially Herat (in modern-day Afghanistan). Here, the art of the book reached its zenith. Royal workshops (kitabkhanas) brought together the finest calligraphers, painters, binders, and illuminators to produce lavishly illustrated manuscripts.

The Timurid style of miniature painting is characterized by its lyrical and often idealized depiction of courtly life, epic battles, and romantic poetry. Artists like Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād, the undisputed master of the Herat School, created complex, harmonious compositions filled with vibrant colors and exquisite detail. These paintings were not mere illustrations; they were masterpieces of narrative art, capturing the emotional and aesthetic spirit of the age.

Legacy of a Golden Age

The Timurid Empire itself was relatively short-lived, fracturing within a century of Timur’s death. Its cultural legacy, however, proved far more enduring. This explosive renaissance created an artistic and intellectual blueprint that was inherited and adapted by the three great Islamic empires of the early modern era.

- The Mughal Empire in India, founded by Timur’s descendant Babur, brought Timurid aesthetics to the subcontinent, culminating in architectural wonders like the Taj Mahal.

- The Safavid Empire in Persia elevated the Timurid tradition of miniature painting and architectural tilework to new heights, as seen in the stunning mosques of Isfahan.

- The Ottoman Empire in Turkey also absorbed Timurid influences, integrating them into their own distinct imperial style.

The story of the Timurid Renaissance is a powerful reminder that history is rarely simple. It demonstrates how the ferocity of a conqueror can, paradoxically, create the conditions for unparalleled artistic and intellectual achievement. The azure domes of Samarkand still stand today, not as monuments to a brutal warlord, but as shimmering testaments to a golden age born from his complex and formidable vision.