What Was a Tally Stick?

At its most basic, a tally stick was a length of polished wood, typically hazelwood, used to record a transaction. When a debt was created or a tax paid, notches and grooves were carved into the stick to represent the amount. The system was meticulously organised:

- A notch the width of a hand represented £1,000.

- A thumb’s width was £100.

- A little finger’s width was £1.

- A simple slice was a shilling.

- A small jab was a penny.

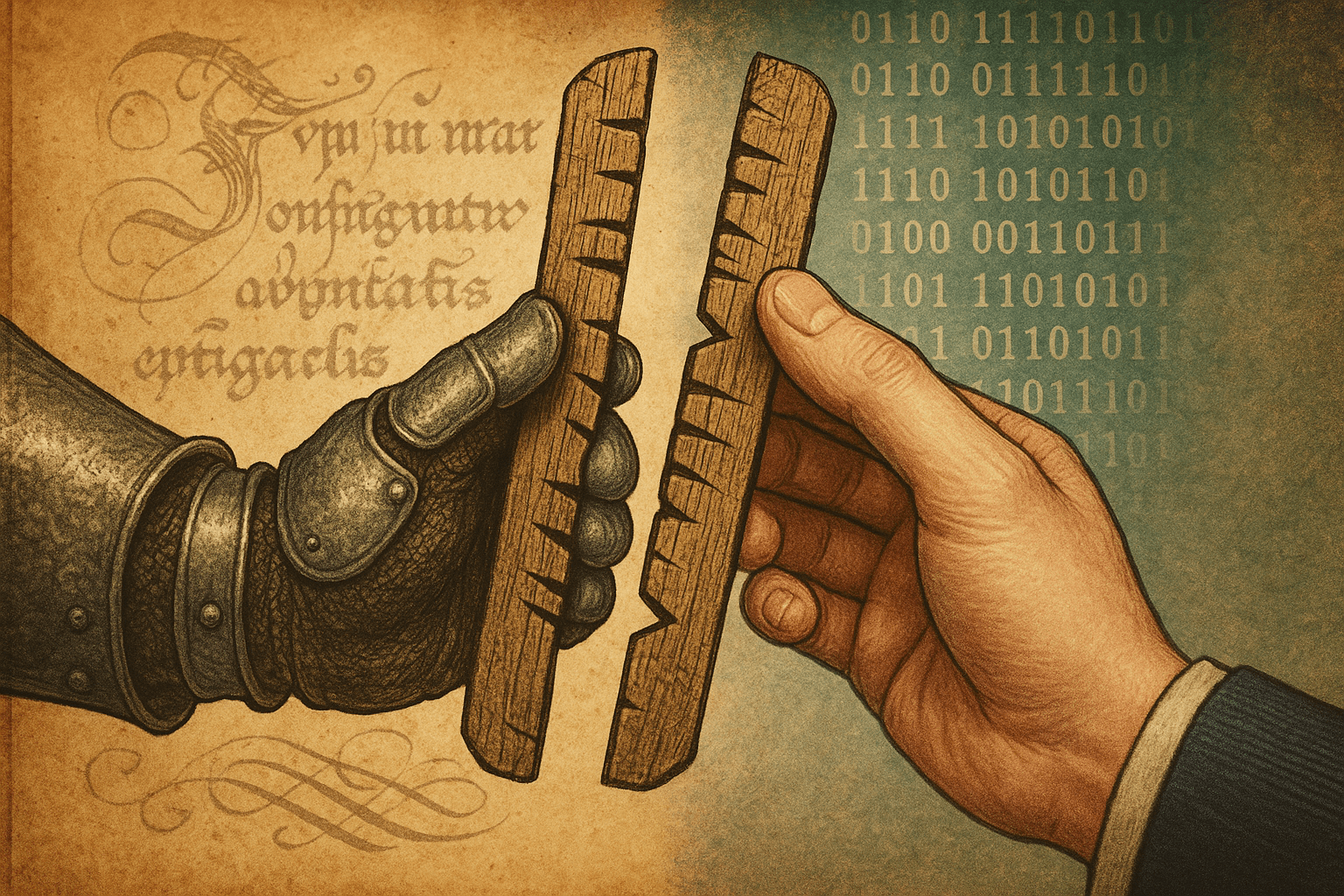

Once the amount was recorded in this way, crucial details like the names of the parties and the date were written on two flat, opposing sides of the stick. Here, however, is where the genius of the system becomes clear. The stick was then split lengthwise, right down the middle, through the notches. The resulting two halves would each have a perfect mirror image of the notches and a portion of the written text.

The longer piece, called the stock, was given to the creditor—the person who was owed money. The shorter piece, called the foil, was given to the debtor. The stock was literally “proof of stock” held in a company or a debt, the origin of our modern financial term “stocks.” The foil acted as the debtor’s receipt. The debt was only officially settled when the two halves were brought back together and they “tallied” perfectly.

The Original Anti-Fraud Device

In a world where literacy was low and forgery was a constant concern, the tally stick was a masterclass in security. It was virtually impossible to tamper with. Think about it: a debtor couldn’t simply shave down their foil to reduce the debt, because it would no longer match the creditor’s stock. Nor could a creditor add more notches to their stock to increase the debt, as these new marks wouldn’t exist on the debtor’s foil.

The unique grain of the wood itself acted as a kind of fingerprint. When split, the wood created a one-of-a-kind surface on each half. Replicating the exact notches, the split, and the wood grain would be a near-impossible feat of forgery. This physical, unalterable record made tally sticks a legally binding proof of debt, accepted in courts and by the Crown itself. Introduced to England by King Henry I around 1100, the system of the Royal Exchequer became the backbone of English state finance for centuries.

From Debt Receipt to Medieval Currency

The tally stick’s role quickly evolved beyond a simple IOU. It became a flexible and powerful form of currency. How? Imagine you are a medieval merchant who has supplied the king with wine for his court, and in return, the Exchequer gives you a tally stick stock for £10. This stick is proof that the government owes you £10.

You could wait to redeem it from the Treasury, but what if you needed to pay your own debts now? Instead of cash, you could simply pass your tally stick stock to your own creditor—say, the farmer who supplied you with grapes. That farmer could then accept the stick as payment, confident that he could either redeem it from the government himself or use it to pay his own taxes. In effect, the stick became transferrable government debt, circulating as a secure form of money that facilitated trade and commerce across the kingdom.

This system was incredibly successful. People had faith in it because the king’s debt was considered good, and the physical security of the sticks was undeniable. It was a thriving system of credit long before the Bank of England and paper currency became dominant.

A Blaze of Obsolete Glory: The Burning of Parliament

For over 700 years, the tally stick was a cornerstone of British finance. But by the late 18th and early 19th centuries, it was becoming an amusing, archaic relic. The founding of the Bank of England in 1694 introduced paper banknotes, and modern bookkeeping methods were taking hold. Yet, the fiercely traditional Exchequer continued to use tallies until the system was officially abolished in 1826.

This left the government with a peculiar problem: what to do with the centuries-worth of old, settled tally sticks filling the cellars of the Houses of Parliament? For years, these vast, dusty mountains of wood sat gathering dust in the Star Chamber.

On October 16, 1834, two junior officials were finally given the task of getting rid of them. Instead of discreetly carting them away or burning them in small batches, they decided on a more expedient solution. They would burn the old tallies in the two large furnaces directly beneath the chamber of the House of Lords. All day, they stuffed the furnaces with bundles of the dry, ancient wood.

The result was catastrophic. The furnaces, designed for burning coal, became white-hot. The intense heat buckled the copper lining of the chimneys and ignited the wood panelling of the rooms above. By evening, smoke was pouring out of the building. The ensuing inferno raged through the night, engulfing and destroying almost the entire medieval Palace of Westminster, including the chambers of both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Firefighters could only save a few ancient sections, such as the magnificent Westminster Hall.

In a final, spectacular act of irony, the physical records of centuries of financial prudence became the instrument of fiery destruction, burning down the very seat of the government they had served. The iconic neo-Gothic Houses of Parliament we see today, complete with the Elizabeth Tower (often called Big Ben), were built on the ashes of the old palace, a monument born from the smoke of obsolete accounting.

The tally stick’s story is a powerful reminder that history’s most effective technologies are not always the most complex. For centuries, a humble piece of wood secured the finances of a kingdom, only to meet its end in a blaze of glory that reshaped the London skyline forever.