A Scholar’s Vision and a New Gospel

The story begins with a man named Hong Xiuquan. Born in 1814 into a modest farming family, Hong possessed a sharp intellect and harbored the singular ambition of every aspiring young man in Qing-dynasty China: to pass the notoriously difficult imperial civil service examinations. Success meant prestige, wealth, and a position in the government bureaucracy. Failure meant a life of obscurity.

Hong tried and failed. And tried and failed again. After his third failure in 1837, the immense psychological pressure pushed him into a complete breakdown. For days, he was wracked by fever and delirious visions. In his dream-state, he was transported to a heavenly realm where a golden-bearded old man lamented that the world was overrun by demons. This venerable father figure gave Hong a sword and, with the help of a middle-aged “Elder Brother”, instructed him to slay the demons.

The vision was vivid but incomprehensible. It was only years later, after failing the exam for a fourth time, that Hong stumbled upon a Christian pamphlet he had been given by a missionary. As he read the tract, written by Liang Fa, the first Chinese Protestant evangelist, everything clicked into place. The old man in his vision was God the Father. The Elder Brother was Jesus Christ. And he, Hong Xiuquan, was God’s second son, a new Messiah tasked with purging the world—and specifically China—of “demons.”

These “demons” were not just spiritual entities. To Hong, they were the corrupt Qing government, the “foreign” Manchu rulers, Confucian tradition, and the Taoist and Buddhist idols that filled the country’s temples.

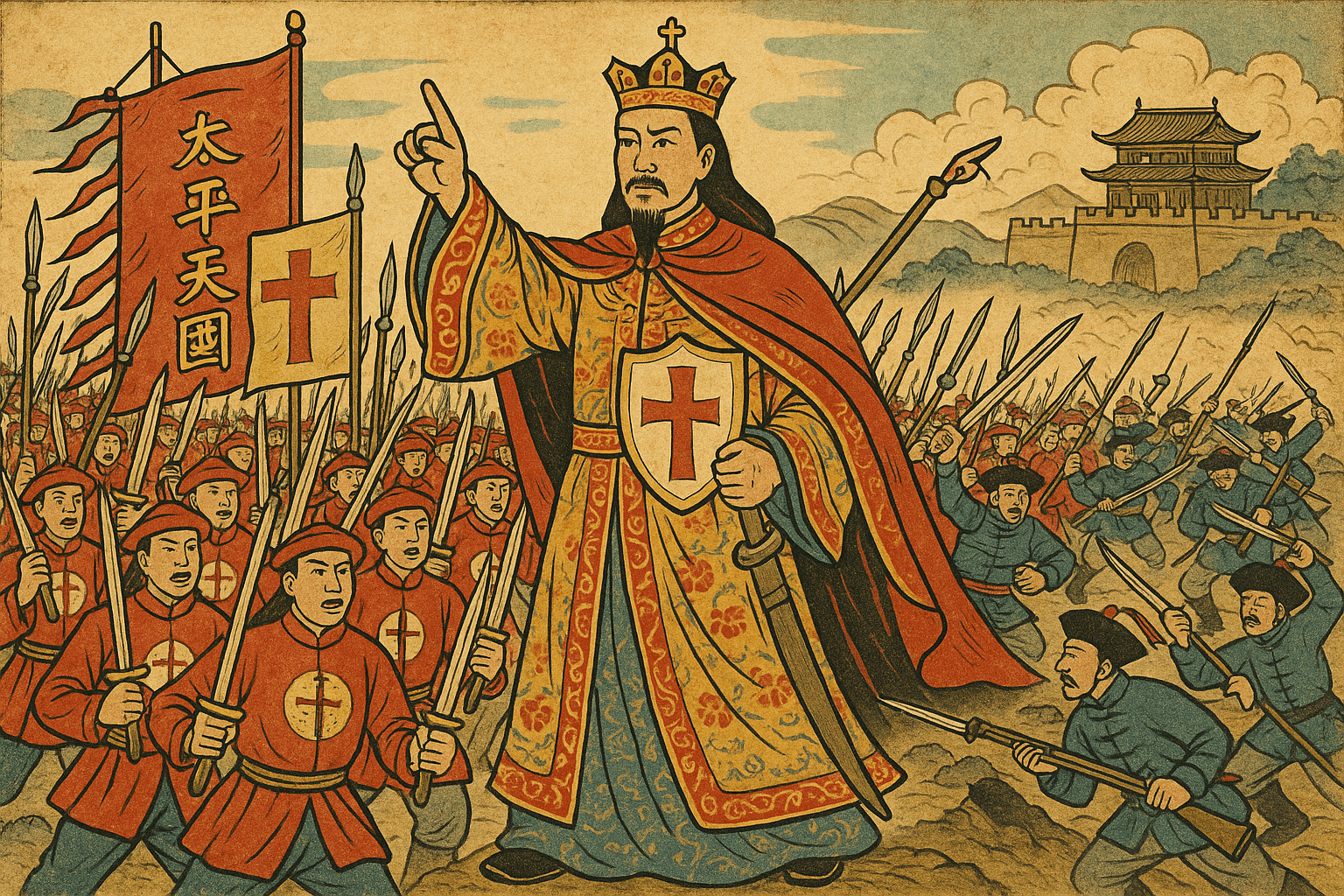

Forging the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace

Hong’s syncretic theology—a unique and potent blend of Protestant Christianity, ancient Chinese utopianism, and his own divine pronouncements—found fertile ground in the beleaguered Chinese countryside. The Qing Dynasty was reeling from the humiliation of the First Opium War, and peasants were crushed by famine, oppressive taxes, and corrupt local officials. People were desperate for change, for a savior.

Hong and his followers formed the “God Worshipping Society.” Their new faith was radical and absolute. They proclaimed a new state: the Taiping Tianguo, or “Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace.” Its tenets were a revolutionary departure from Chinese society:

- Radical Monotheism: Only one God—their God—could be worshipped. Taiping followers smashed ancestral tablets and destroyed Buddhist and Taoist temples across the regions they conquered.

- Strict Moral Code: Alcohol, opium, gambling, tobacco, and adultery were all forbidden, often on pain of death. In its early, zealous days, the Kingdom even enforced strict separation of the sexes.

- Social Equality: In a truly revolutionary move, the Taipings declared that men and women were equal. They outlawed the painful practice of foot-binding, and women were allowed to sit for civil service exams and even serve as military officers.

- Land Reform: All land was declared property of the Heavenly Kingdom and was to be redistributed equally among its followers, a policy that held immense appeal for the landless peasantry.

The Scythe of God: A Fourteen-Year War

In 1851, from their base in the southern province of Guangxi, the Taipings launched their rebellion. Their army, infused with religious fervor and disciplined by their austere code, proved stunningly effective. They swept north through the Yangtze River valley, their numbers swelling with desperate peasants and disaffected workers.

In 1853, they achieved their greatest prize: the great southern city of Nanjing. They renamed it Tianjing, the “Heavenly Capital”, and made it the heart of their new empire. For a time, it seemed the Qing Dynasty was on the verge of collapse. The Taipings controlled a vast swath of territory, and their armies threatened both Shanghai and Beijing.

The war that ensued was one of almost unimaginable brutality. It was a total war, where civilian populations were routinely massacred by both sides. Cities that were besieged for months or even years were reduced to barren wastelands where inhabitants resorted to cannibalism. The fighting was not just between armies but between ideologies, with the Taipings fighting to create a new world and the Qing fighting to preserve the old one.

Internal Rot and Final Collapse

Despite their initial success, the Heavenly Kingdom contained the seeds of its own destruction. The utopian ideals began to fray under the pressures of power. Hong Xiuquan retreated into the decadent pleasures of his palace, communicating his “divine” will through written edicts and leaving governance to his lieutenants.

This led to jealousy and vicious infighting. In 1856, the “Tianjing Incident” saw a bloody purge where the East King, Yang Xiuqing—a powerful leader who claimed to channel the voice of God the Father—was murdered along with tens of thousands of his followers. This internal bloodbath crippled the Taiping leadership and shattered their unity.

Meanwhile, the Western powers (Britain and France), who had initially watched with some curiosity, ultimately decided the devil they knew was better than the one they didn’t. The Taipings’ anti-foreign stance and their disruption of trade were threats to their interests. They provided military support, training, and leadership to the Qing forces, most famously through the “Ever-Victorious Army” led first by the American Frederick Townsend Ward and later by the British officer Charles “Chinese” Gordon.

Besieged, starved, and torn apart from within, the Heavenly Kingdom crumbled. In June 1864, with Qing forces massing outside Nanjing, Hong Xiuquan died, likely by consuming poison. A month later, the city fell in a storm of fire and blood. The Qing soldiers exacted a terrible revenge, killing an estimated 100,000 people in just three days.

The Legacy of a Bloody Dream

The Taiping Rebellion was over, but its scars ran deep. With a death toll estimated between 20 and 30 million, it remains one of the deadliest military conflicts in human history. The war devastated China’s richest provinces, shattered its economy, and irrevocably weakened the Qing Dynasty, which would limp on for another half-century before finally collapsing in 1911.

Today, the Taiping Rebellion is remembered as a complex and tragic episode. Was it a righteous peasant uprising against a corrupt regime? Or a destructive cult led by a madman? In a way, it was both. It stands as a chilling testament to how powerful ideas—even those born in a feverish dream—can mobilize millions, topple empires, and unleash a holy war of catastrophic proportions.