A Civilization Born of the Monsoon Winds

Stretching from modern-day Somalia down to Mozambique, the Swahili Coast was perfectly positioned for commerce. Its existence was made possible by a remarkable force of nature: the monsoon winds. These predictable, seasonal winds acted like a giant, natural engine for the Indian Ocean. From November to March, the winds blew southwest, carrying ships from Arabia, Persia, and India towards Africa. From April to October, they reversed, allowing a return journey with holds full of African treasures.

The inhabitants of this coast were Bantu-speaking peoples who had settled there centuries earlier. They were farmers, fishers, and skilled boat builders. As early as the 1st century CE, a Greek merchant’s guide called the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea described trading ports along this coast, known then as Azania. But it was in the medieval period, from roughly the 8th to the 15th century, that these small settlements blossomed into powerful, independent city-states.

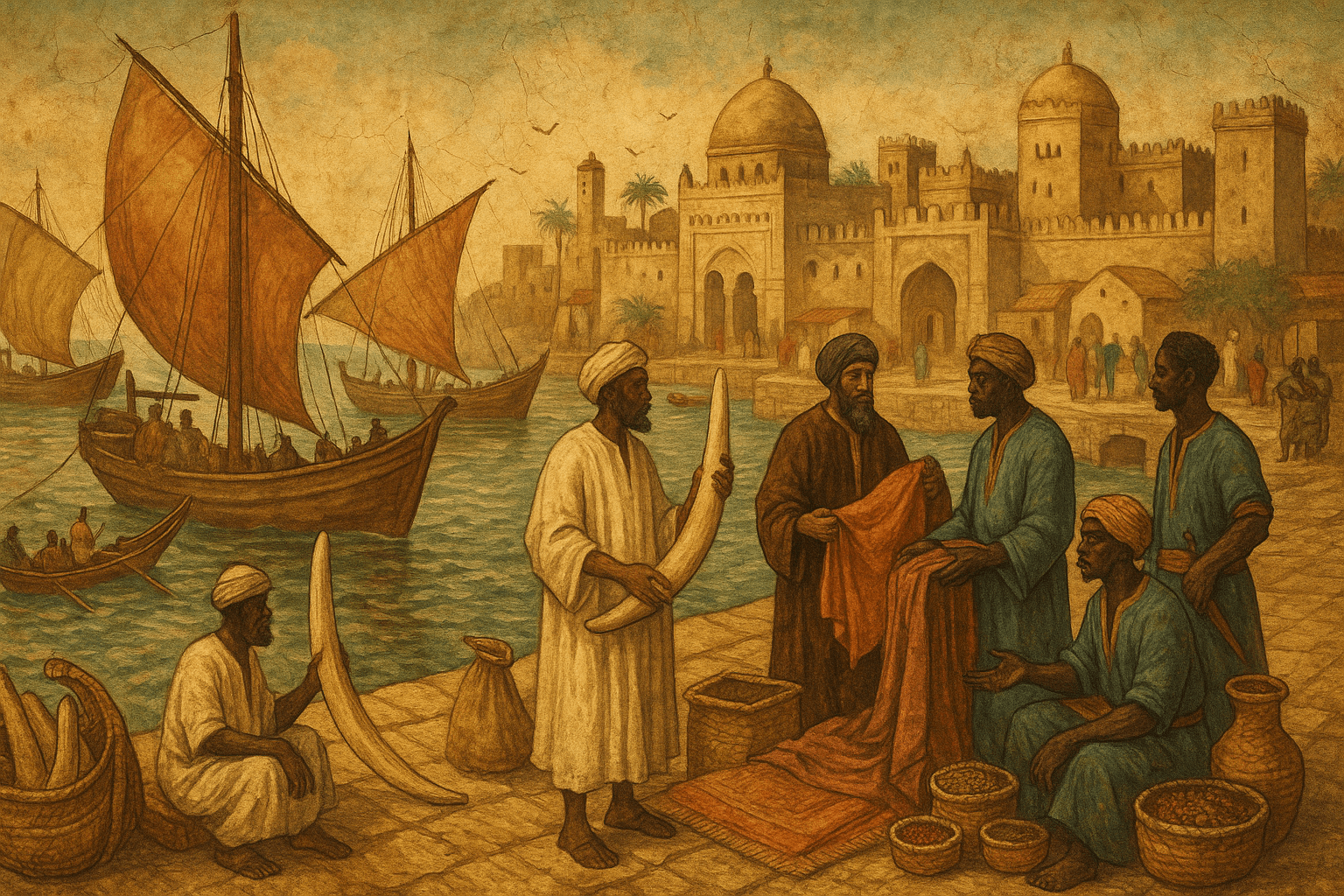

The Engine of Trade: Gold, Ivory, and Dhows

The Swahili city-states were not producers of wealth, but facilitators of it. They acted as the essential middlemen, the brokers connecting the resource-rich African interior with the manufacturing powerhouses of Asia. This trade was astonishing in its scope and variety.

From the African interior, caravans brought unimaginable riches to the coastal ports:

- Gold: Sourced from the mines of the mighty Kingdom of Zimbabwe in the south, this was the most sought-after commodity.

- Ivory: African elephant tusks were prized across Asia and Europe for carving and ornamentation.

- Other Goods: Timber (especially mangrove poles for construction), animal skins, iron, and, tragically, enslaved people were also major exports.

In return, the elegant dhows sailing in on the monsoons brought the finished goods of the world:

- From China: Exquisite porcelain and silk, tangible symbols of wealth and status. Archaeologists have unearthed troves of Ming dynasty pottery in the ruins of Swahili palaces.

- From India: Brightly colored cotton textiles, spices, and beads.

- From Persia and Arabia: Glazed earthenware, glassware, dates, and books.

The Swahili merchants grew fabulously wealthy managing this flow of goods, levying taxes, and outfitting their own trading expeditions.

A Fusion of Cultures: The Birth of Swahili

This constant interaction didn’t just exchange goods; it exchanged ideas, beliefs, and DNA, creating a unique and vibrant culture that we call Swahili. The very name, from the Arabic sawāḥil (coasts), points to its mixed origins. It was African at its core, but with a deep and pervasive Arabic and Persian influence.

Language: The Swahili language is a perfect emblem of this fusion. It is a Bantu language in its grammar and structure, but its vocabulary is enriched with thousands of words from Arabic, particularly terms related to trade, religion, and law.

Religion: Islam arrived with the Arab traders and was gradually adopted by the Swahili ruling elite. It provided a shared religious and legal framework that strengthened commercial ties with the wider Islamic world. Magnificent mosques, built from coral stone, became the centerpieces of the cities.

Architecture: The wealthy merchants built elaborate, multi-story houses out of carved coral blocks. These homes featured cool inner courtyards, decorative niches for displaying Chinese porcelain, and famously, intricately carved wooden doors that served as status symbols for the family within. Zanzibar’s Stone Town still offers a breathtaking look at this architectural style.

A Glimpse into the Great City-States: Kilwa the Mighty

Dozens of city-states lined the coast, including Mombasa, Malindi, Lamu, and Mogadishu, each vying for a greater share of the trade. For a time, the most powerful of them all was Kilwa Kisiwani, located on an island off modern-day Tanzania.

Kilwa’s strategic location allowed it to control the gold trade from the port of Sofala to the south. The wealth that flowed through the city was legendary. When the great Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta visited in 1331, he described Kilwa as “one of the most beautiful and well-constructed towns in the world.” He marveled at its grand mosque and the hospitality of its sultan.

The rulers of Kilwa built the Palace of Husuni Kubwa, a sprawling complex overlooking the ocean with over 100 rooms, courtyards, and an octagonal swimming pool. This wasn’t a mud-hut village; it was a center of global power and luxury, a contemporary to the great cities of medieval Europe and Asia.

Disruption and Legacy

This golden age came to a violent end at the turn of the 16th century. In 1498, the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope, seeking to bypass the old trade routes and seize control of the spice trade. The Portuguese were not interested in participating in the Swahili network; they wanted to dominate it.

Armed with ship-mounted cannons, a technology the Swahili did not possess, the Portuguese sacked and burned the defenseless cities one by one. They built forts, imposed taxes, and completely disrupted the delicate balance of the monsoon trade that had sustained the coast for centuries. The independent city-states went into a steep decline.

Yet, the Swahili culture did not die. It endured, adapting to new circumstances. Today, the Swahili language is a lingua franca spoken by over 100 million people across East and Central Africa. The coral ruins of Kilwa and the living history of Lamu and Zanzibar’s Stone Town stand as powerful testaments to this brilliant civilization. They remind us that long before the modern era, the world was deeply interconnected, and the Swahili Coast was not a forgotten backwater, but a glittering jewel at the very heart of it.