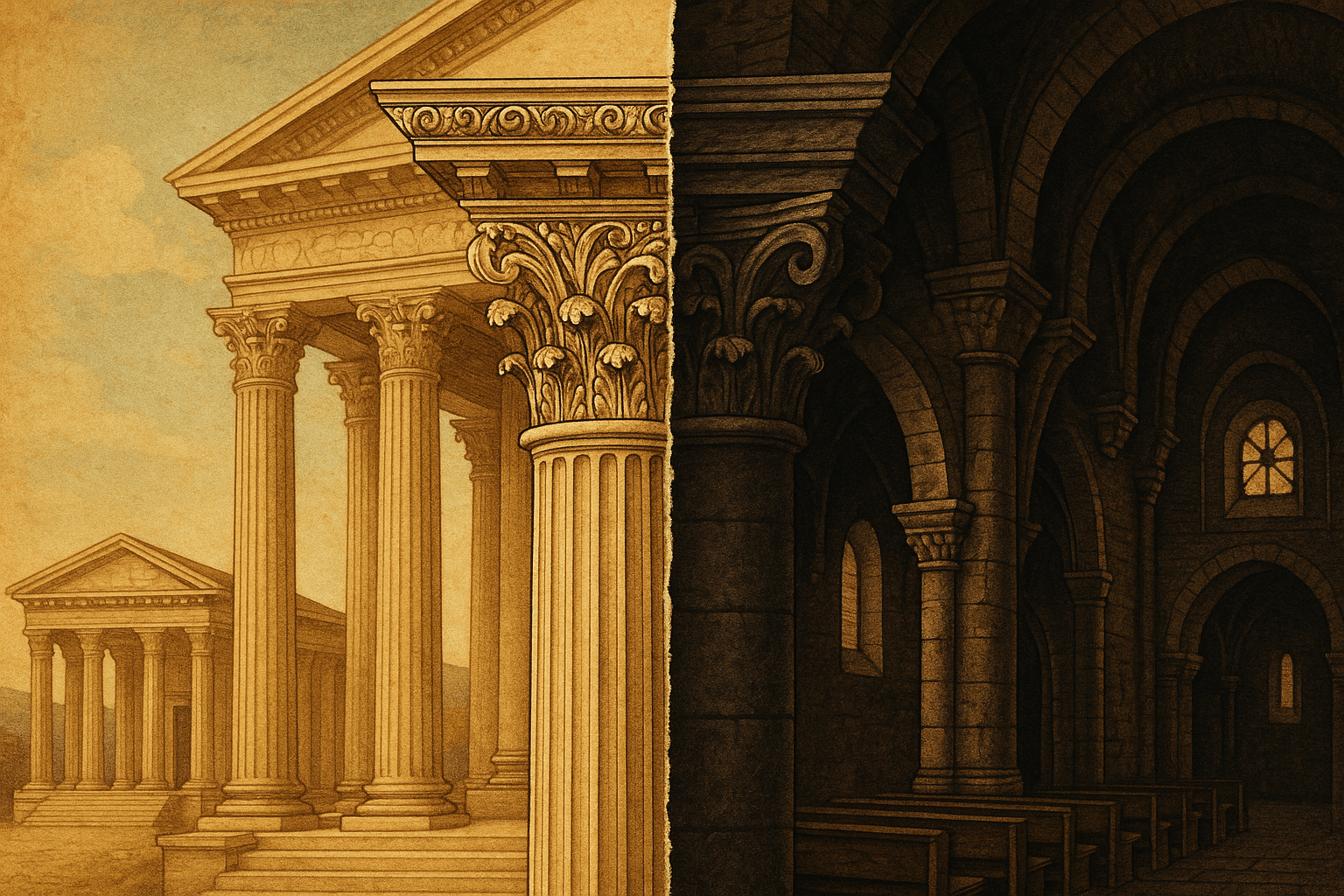

The Latin word spolia literally means “spoils”, as in the spoils of war. In architectural terms, it refers to the practice of taking building materials from old structures and reusing them in new ones. In the centuries after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the city of Rome—once the caput mundi, the capital of the world—became the world’s most magnificent and convenient quarry. This practice of spolia is more than just scavenging; it’s a physical chronicle of Rome’s transformation, telling a story of decline, survival, and rebirth written in stone and marble.

From Majestic Capital to Convenient Quarry

To understand spolia, we must first picture post-Roman Rome. During the height of the Empire in the 2nd century AD, the city was a sprawling metropolis of over a million people. It was filled with monumental structures: the Colosseum, vast public baths like those of Caracalla and Diocletian, countless temples, towering imperial fora, and triumphal arches.

By the 8th century, however, wars, plagues, and political collapse had reduced the population to a mere fraction of its former size—perhaps only 30,000 people. This tiny community lived huddled in small pockets of the city, surrounded by the gigantic, decaying skeletons of their ancestors’ achievements. Maintaining these massive buildings was impossible, and the technology and resources to quarry new marble from distant mountains were lost.

Yet, the need to build continued. New churches, defensive towers, and homes were required. The solution was all around them. Why go to the trouble of quarrying and transporting a new column when a perfectly good one was standing in the ruins of the nearby Temple of Isis or the Forum of Trajan? Ancient Rome became a vast, open-air warehouse of high-quality, pre-cut, and beautifully carved materials, free for the taking.

The Ideology of Reuse: Power, Piety, and Legitimacy

While practicality was the primary driver, spolia was also a deeply symbolic act. Its use was a conscious choice that carried powerful ideological messages.

- The Triumph of Christianity: Early Christians readily dismantled pagan temples to build their new churches. This was a potent physical statement: the false gods were literally being torn down to provide the foundation for the one true God. Incorporating columns from a temple dedicated to Jupiter into a basilica was a visible sign of Christianity’s victory over paganism. The original St. Peter’s Basilica, commissioned by the Emperor Constantine himself, was famously built using columns taken from various older, likely pagan, Roman buildings.

- Claiming a Legacy: For medieval Popes and nobles, using spolia was a way to connect themselves to the glory and authority of the ancient Roman Empire. By incorporating imperial porphyry (a deep purple stone reserved for emperors) or magnificent columns into their own buildings, they were visually appropriating the legacy of the Caesars. They weren’t just reusing stone; they were claiming to be the rightful inheritors of Roman power and prestige.

This wasn’t always chaotic looting. For periods, the process was regulated by officials who would grant licenses to builders, allowing them to “excavate” specific ruins. It was an organized demolition and redistribution system, recycling an empire to build a new world.

Reading the Stones: Where to See Spolia Today

When you know what to look for, you can see spolia everywhere in Rome. The city becomes a living museum to the practice.

Basilica di Santa Maria in Aracoeli: Situated on the Capitoline Hill, the ancient citadel of Rome, this church is a prime example. Its nave is lined with 22 columns, none of which are identical. A close look reveals they are of different heights (adjusted with varying bases), materials, and styles. One even bears an inscription, “A CUBICULO AUGUSTORUM”, indicating it came from a private room in an imperial palace.

Arch of Constantine: This famous arch, built in the 4th century, shows that spolia was used even before the Empire’s final collapse. To speed up construction and link himself with revered “good emperors”, Constantine’s builders lifted entire sculptural panels from earlier monuments dedicated to Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius and incorporated them into his new arch.

Basilica di Santa Maria in Trastevere: The 22 massive Ionic columns lining its nave were hauled from the nearby ruins of the Baths of Caracalla. On some of the capitals, you can still see carved heads of Egyptian deities like Isis and Serapis, a clear sign of their pagan origin, now pressed into the service of a Christian church.

Even beyond grand basilicas, you’ll find spolia in the small details: a Roman sarcophagus repurposed as a fountain basin, a fragment of a Latin-inscribed frieze mortared into a medieval wall, or the intricate Cosmatesque floors of churches, made from thousands of tiny, colourful marble triangles salvaged from imperial villas.

The Renaissance and the Shift in Perspective

The practice of using ancient Rome as a quarry continued well into the Renaissance. In fact, the construction of the new St. Peter’s Basilica in the 16th and 17th centuries was one of the single most destructive events for the ruins of the Roman Forum. But the Renaissance also brought a profound shift in attitude.

Humanist scholars and artists began to look at the ruins not just as a source of raw materials, but as objects of historical and aesthetic value in themselves. They studied the proportions of the Pantheon and sketched the reliefs on Trajan’s Column. In a famous 1519 letter to Pope Leo X, the artist Raphael lamented the “shame of our age” that had allowed Rome to be so relentlessly cannibalized. He pleaded for the preservation of what was left.

This was a turning point. It marked the slow transition from viewing Rome’s past as a quarry to be exploited to an archaeological heritage to be protected. The idea of the open-air museum was born.

Today, as we walk the streets of Rome, we are walking through the evidence of this epic story. Spolia represents both destruction and continuity. It is the tangible link between the imperial city of the Caesars and the papal city of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. It shows us that Rome did not simply fall; it was dismantled, reconfigured, and recycled into the city we see today.