Brothers in Arms, Strangers in Law: The Plight of the Socii

For centuries, the Roman Republic was not a unified nation-state in the modern sense, but the dominant city in a complex patchwork of alliances across the Italian peninsula. These allies, known as the Socii (“Companions”), were bound to Rome by individual treaties. They maintained local autonomy but were obligated to provide soldiers for Rome’s armies. And provide they did. By the 2nd century BC, the Socii contributed as many, if not more, troops to Rome’s legions as the citizens themselves.

It was Samnite, Marsian, and Umbrian blood that helped fill the ranks against Carthage, conquer Greece, and expand Roman power across the Mediterranean. They shared the dangers of the battlefield, the discipline of the camp, and the culture of a militarized society. Yet, when the fighting was done, a deep inequality remained. They were partners in war, but subjects in peace.

The Seeds of Discontent: Why Demand Citizenship?

As Rome’s power swelled, the disadvantages of being a non-citizen ally became increasingly stark. The simmering resentment of the Socii grew from a number of key grievances:

- Military Burden without Full Reward: While they did a huge portion of the fighting and dying, the Italian allies received a smaller share of the spoils of war—captured loot and conquered land.

- Economic Squeeze: The massive influx of wealth into Rome benefited a small Roman elite. Ambitious senators bought up huge tracts of land in Italy, often dispossessing the very Italian farmers who were away fighting Rome’s wars. When reformers like the Gracchi brothers attempted to redistribute public land to the poor, this relief was primarily for Roman citizens, excluding the allies whose land had often been absorbed into that “public” pool in the first place.

- Legal Vulnerability: Perhaps the most galling inequality was the lack of legal protection. A Roman citizen had the right of appeal (provocatio ad populum), protecting them from arbitrary punishment by magistrates. The Socii had no such right. They could be flogged, dispossessed, or even executed at the whim of a Roman official. A famous (and perhaps embellished) story tells of a Roman consul’s wife who, wanting to use the men’s baths in an allied town, had the local magistrate stripped and whipped in the marketplace simply because he was slow to clear them out for her. True or not, the story captured the profound sense of humiliation and powerlessness felt by the Italian elite.

- Political Impotence: The allies had no voice in the Senate and no vote in the assemblies. They had no say in the declarations of war they were forced to fight, nor in the laws that increasingly governed their lives.

The Spark That Ignited Italy: Livius Drusus and the Assassination

The push for citizenship was not new, but by 91 BC, tensions had reached a boiling point. Into this volatile situation stepped a Roman tribune, Marcus Livius Drusus. A man of the establishment, Drusus was an unlikely champion for the Italian cause. He proposed a broad package of reforms, including land grants, cheaper grain, and, most controversially, the extension of Roman citizenship to all Italians.

Drusus lobbied tirelessly, building a fragile coalition of supporters. But the Roman elite was terrified. Sharing citizenship meant sharing power, diluting their voting blocs, and granting others access to lucrative provincial commands and state contracts. The opposition was fierce and uncompromising. In late 91 BC, as Drusus returned home one evening, he was struck down in his own doorway by an unknown assassin. His dying words were reportedly: “My friends and relations, will the Republic ever have a citizen like me again?”

The murder of Drusus was the final straw. It was a clear and brutal message to the Italians: peaceful reform was impossible. If they wanted the rights of Romans, they would have to take them by force.

Italia vs. Rome: A War of Secession and Identity

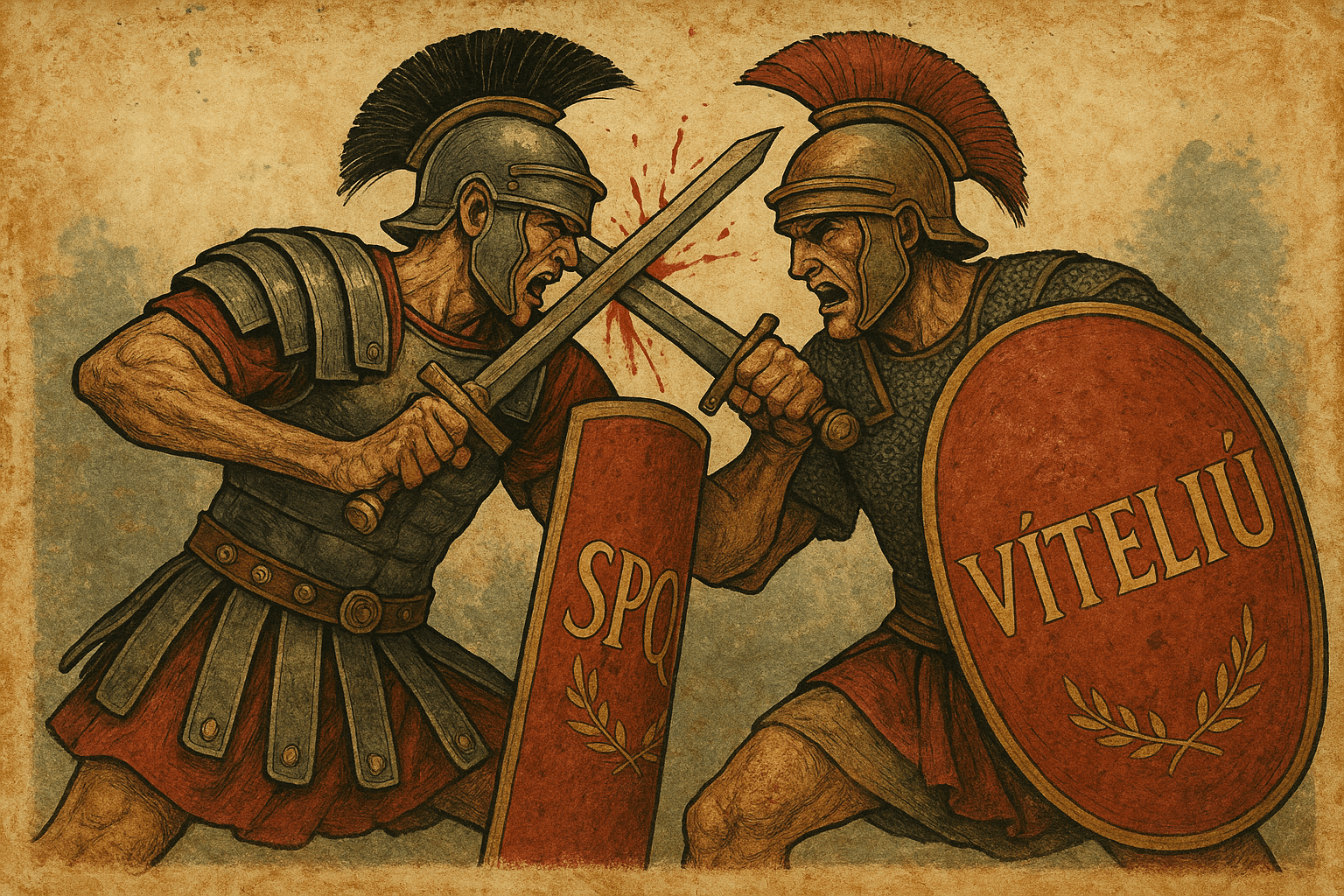

The rebellion exploded in the town of Asculum, where a Roman praetor and his staff were massacred by an enraged mob. The fire of revolt spread like wildfire across central and southern Italy. The rebels—primarily proud and warlike peoples like the Samnites and Marsi—were not a disorganized rabble. They were disciplined soldiers trained in Roman tactics, often led by men who had served as officers in Roman armies.

In a bold move, they formed their own confederation, which they called Italia. They established a capital at Corfinium (renamed Italica), created their own senate of 500 members, and even minted their own coins. This propaganda was powerful: one famous silver denarius depicted the Italian Bull goring the Roman Wolf—a potent symbol of their challenge to Roman dominance.

The war was a horrific, intimate affair. It was fought not with grand, sweeping battles, but in countless sieges, ambushes, and brutal skirmishes across the mountainous spine of Italy. It pit former comrades-in-arms against each other. Experienced Roman commanders like Gaius Marius and the rising star Lucius Cornelius Sulla were tasked with putting down the rebellion. For three years, the peninsula was savaged by a conflict that may have claimed over 300,000 lives.

A Political Victory in Military Defeat: The Consequences of the War

On the battlefield, Rome’s immense resources and seasoned generals eventually began to turn the tide. By 88 BC, most of the major Italian strongholds had fallen, and the rebellion was largely crushed. Militarily, Rome had won.

But politically, the Italians had achieved their primary goal. Realizing that a purely military solution would be ruinously costly and might not even be possible, Rome’s leaders had chosen pragmatism over pride. As early as 90 BC, the Lex Julia was passed, granting full citizenship to all allied communities that had not rebelled or that agreed to lay down their arms immediately. This was a clever move to peel away wavering allies from the rebel cause. A year later, in 89 BC, the Lex Plautia Papiria extended citizenship to any individual Italian who registered with a Roman praetor within 60 days.

The war was over, and the Italians were now Romans. This had several profound consequences:

- The Unification of Italy: The Social War effectively erased the old lines between “Roman” and “Italian.” It forged a unified Italian peninsula and laid the groundwork for the concept of Italy as a singular geographic and political entity under Roman rule.

- Overburdening the Republic: The institutions of the Roman Republic were designed for a small city-state, not a massive nation-state. Suddenly doubling the citizen body placed an unbearable strain on the political system. The assemblies became unwieldy, and the new citizens were often mobilized by powerful individuals rather than traditional state structures.

- The Rise of the Generals: The new Italian citizens often felt a greater loyalty to the generals (like Marius and Sulla) who had fought in the war and administered their enfranchisement than they did to the distant and abstract Senate in Rome. This shift in loyalty from the state to the individual commander was a crucial ingredient in the civil wars that followed and the ultimate collapse of the Republic.

The Social War stands as a stark lesson in the dangers of withholding rights and representation. Rome’s refusal to share the privileges of citizenship with those who shared its burdens led to a devastating and unnecessary conflict. While the allies “lost” the war, they won the peace, fundamentally reshaping what it meant to be Roman. In doing so, however, they helped create a new, larger Rome that the old Republic could no longer contain, paving the way for the age of emperors.