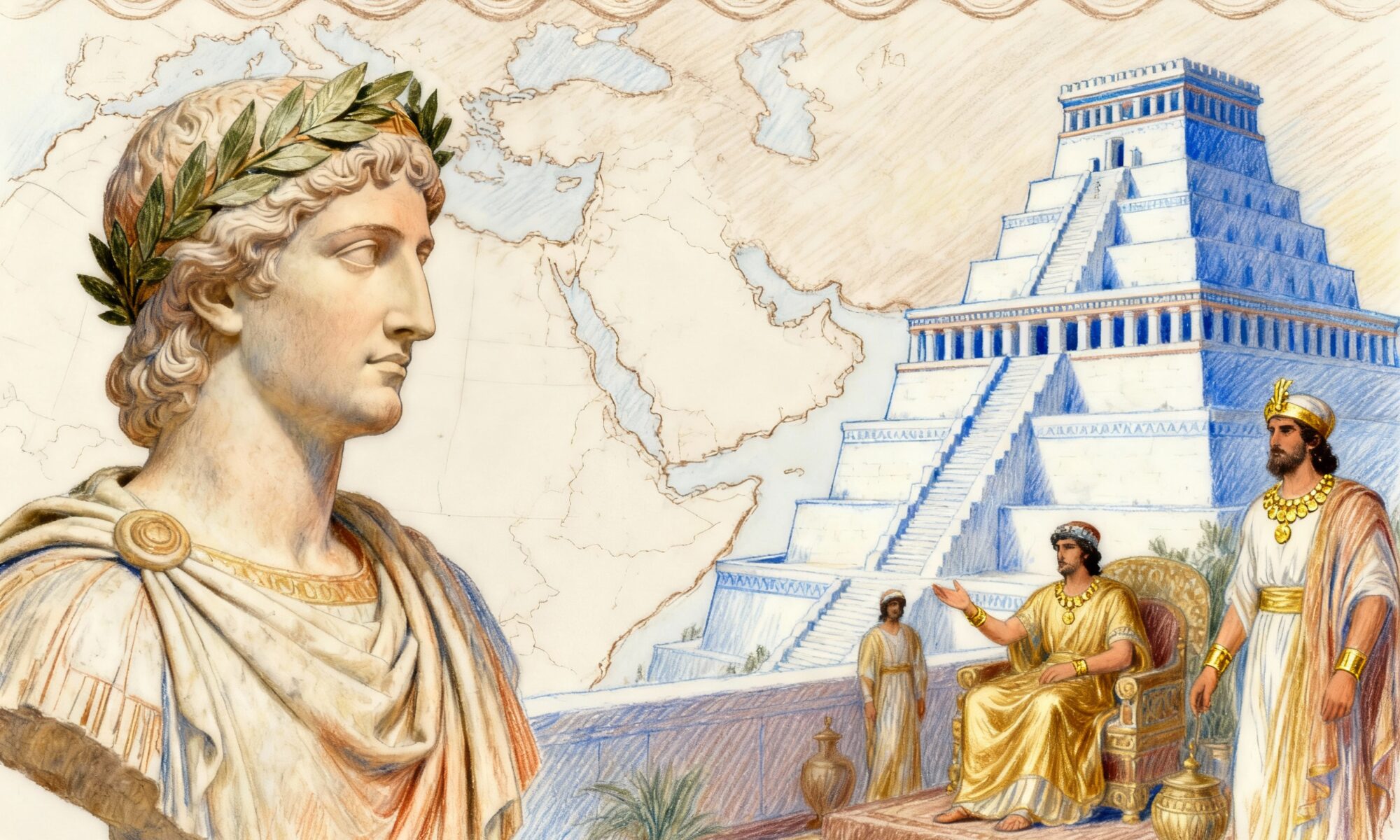

When we think of the great empires of antiquity, names like Rome, Persia, and the Egypt of the Pharaohs immediately spring to mind. Even among the Hellenistic kingdoms forged from Alexander the Great’s conquests, we often remember Ptolemaic Egypt, with its famous library and legendary queen, Cleopatra. Yet, the largest, most populous, and arguably most complex of these successor states often fades into the historical background: the Seleucid Empire.

For nearly 250 years, this sprawling dynasty controlled a vast territory stretching from modern-day Turkey to the borders of India. It was a vibrant, multicultural empire that served as a crucial bridge between East and West. So why is its legacy so often lost in the shadows of its contemporaries? The story of the Seleucid Empire is one of grand ambition, fascinating cultural fusion, and the immense challenge of holding together a world.

From a General’s Ambition to a Sprawling Empire

The empire’s story begins with its founder, Seleucus I Nicator, or “the Victor.” One of Alexander’s most capable generals, Seleucus navigated the treacherous “Wars of the Diadochi” (Wars of the Successors) with cunning and military prowess. After a period of exile in Egypt, he returned to reclaim the satrapy of Babylonia in 312 BCE—a date that would become the official start of the Seleucid Era.

Through strategic alliances and decisive victories, most notably at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE, Seleucus consolidated control over the lion’s share of Alexander’s Asian territories. At its zenith, his empire included:

- Anatolia (modern Turkey)

- The Levant (Syria, Lebanon, Judea)

- Mesopotamia (modern Iraq)

- Persia (modern Iran)

- Parts of Central Asia and the Indus Valley

He founded a new capital, Seleucia-on-the-Tigris, which grew into one of the world’s great metropolises, and his son, Antiochus I, later established another major capital in the west, Antioch-on-the-Orontes. This dual-capital system was a pragmatic recognition of the empire’s sheer scale.

A Crucible of Cultures: Greek Cities in a Persian World

The most fascinating aspect of the Seleucid Empire was its unique cultural character. The dynasty’s rulers were Macedonian-Greeks, and they pursued a vigorous policy of Hellenization. They founded dozens of new cities and military colonies (katoikiai) on the Greek model, complete with gymnasiums, theaters, and temples to the Olympian gods. Cities like Antioch and Apamea became glittering centers of Greek language, philosophy, and art deep within Asia.

However, the Seleucids were not simply cultural imperialists. They were ruling over ancient and sophisticated civilizations—Babylonians, Persians, Jews, and many others—who vastly outnumbered the Greek and Macedonian colonists. To govern effectively, the Seleucids had to adapt.

They adopted the pre-existing Persian administrative system of satrapies, employing local elites to help govern the provinces. They participated in local religious rituals, sometimes identifying Greek gods with local deities in a process known as syncretism. Royal propaganda often presented the king in a Persian style, emphasizing grandeur and divine right, even as he was portrayed as a champion of Hellenism to his Greek subjects. The remarkable archaeological site of Ai-Khanoum, in modern Afghanistan, perfectly illustrates this blend: a Greek-style city with a gymnasium and Corinthian columns, but also an oriental-style palace and evidence of non-Greek religious practices.

The Weight of a World: Constant Struggle and Fragmentation

The empire’s greatest strength—its size—was also its fatal weakness. Governing such an immense and diverse territory was a monumental task in an age of horse-and-cart communication. From the very beginning, the empire was under pressure from all sides.

External Wars: The Seleucids were locked in a series of six brutal conflicts with their Ptolemaic rivals in Egypt, known as the Syrian Wars. These wars, fought primarily over control of the valuable southern Levant (Coele-Syria), drained the treasury and diverted military resources for generations.

Internal Rebellion: The vast eastern provinces were the first to break away. In the mid-3rd century BCE, the satrap of Bactria (roughly modern Afghanistan) declared independence, creating the Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. Shortly after, the Parthians, a nomadic Iranian people, established a kingdom in Persia under their leader Arsaces I. The rise of Parthia would prove to be a dagger in the heart of the empire, as it progressively severed the Seleucid heartland in Syria and Mesopotamia from its eastern territories.

The most famous internal conflict was the Maccabean Revolt in Judea (167–160 BCE). Sparked by King Antiochus IV Epiphanes’s aggressive Hellenization policies and his desecration of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, the revolt exposed the limits of Seleucid authority and the fierce resistance that could arise from its subject peoples. While the Seleucids eventually granted the Jews autonomy, the revolt further destabilized their hold on the crucial Levantine corridor.

Decline and the Roman Shadow

By the 2nd century BCE, the Seleucid Empire was a shadow of its former self, weakened by territorial loss and constant warfare. The final blow came not from the east, but from the west: the rising power of Rome.

The Seleucid king Antiochus III “the Great” made a bold attempt to restore the empire’s glory, campaigning as far as India and challenging Roman influence in Greece. His ambition led to a disastrous confrontation. At the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BCE, the Roman legions decisively crushed the Seleucid army. The resulting Treaty of Apamea forced the Seleucids to pay a crippling war indemnity, give up all their territory in Anatolia, and scuttle their navy. The empire was broken as a great power.

The following century was marked by near-constant dynastic civil wars, with cousins and brothers murdering each other for a throne that controlled an ever-shrinking territory. The empire was reduced to little more than Syria. The final, undignified end came in 63 BCE. As the Roman general Pompey the Great swept through the East, he found the pathetic remnants of the Seleucid realm and unceremoniously declared it a Roman province.

The Lost Legacy

The Seleucid Empire is “lost” not because it was insignificant, but because it was succeeded by powers—the Parthians in the East and the Romans in the West—who built their own powerful legacies on its foundations. Unlike Ptolemaic Egypt, which remained intact until its famous end, the Seleucid state was dismembered piece by piece.

Yet, its impact was profound. For over two centuries, it was the primary conduit for Hellenistic culture into Asia. It created a common Greek dialect (Koine) that became the language of administration and trade across the Near East. The cities it founded remained centers of culture and commerce for centuries, and the Greek influence it brought to regions like Bactria and even India left a lasting artistic and cultural mark. The Seleucid legacy is not found in triumphant monuments, but in the subtle, enduring fusion of cultures that it fostered across a forgotten world.